Drawing the Line

Dr. John Jeremiah Bigsby arrived on May 7, 1821, in Waterloo, “a sleepy little cluster of houses at the head of the river Niagara, and on the Canadian side of Lake Erie.” He found the entrance to the lake blocked by a massive ice jam some sixty kilometres long, impeding him, and the other members of his survey party, from embarking on their summer’s work.

“We were told that, by the help of a strong south-west wind, all that immense body of ice would crack and rend, and come tumbling down the river Niagara in ragged fragments,” Bigsby wrote in his memoir, The Shoe and Canoe, or Pictures of Travel in the Canadas. “And so it fell out; but we waited in a wretched pot-house for six days.”

Bigsby, an English physician and an avid traveller, was one of hundreds of people who served between 1816 and 1827 on the boundary commissions that were tasked with settling the border between the United States and the colonies of British North America.

“I need not say that the field service of this Commission was rendered arduous by the heats, severe labour, by the provisions being salt, by annoying insects, heavy rains, and by the unhealthiness of some of the districts under examination,” Bigsby wrote, noting that some surveyors abandoned the task, “subdued by toil and exposure.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

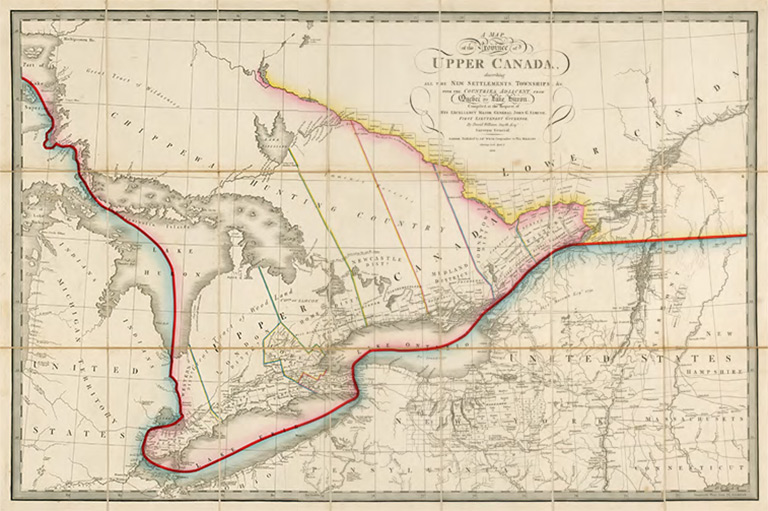

And yet the work of the surveyors, draftsmen, chainmen, axmen, boatmen, labourers, carriers, and cooks — not to mention the agents who managed the operations and the commissioners who carried out the diplomatic end of the affair — created a lasting impact on Canada and the United States. Their collective efforts shaped the eastern border between the two countries, from the Atlantic coast to beyond the western edge of Lake Superior — a border that endures to the present day.

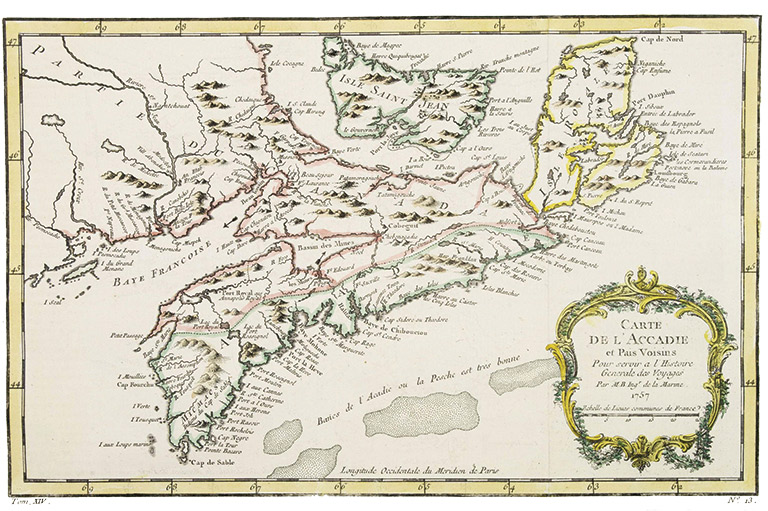

The original boundary between the United States and the British North American colonies had been defined in the terms of the 1783 Treaty of Paris, ending the American War of Independence. But, when the War of 1812 broke out, only a few kilometres of the border had actually been agreed upon: the line where the St. Croix River separates part of New Brunswick from what is now the state of Maine. The rest of the boundary, all the way west to Lake of the Woods — about five hundred kilometres beyond Lake Superior — remained contested.

The War of 1812 proved so militarily inconclusive that, when peace was declared with the Treaty of Ghent on December 24, 1814, the two parties simply agreed to revert to the pre-war borders. But, since nobody knew where the borders actually were, the treaty created four boundary commissions that were empowered to explore, survey, map, and decide the unresolved stretches of the border.

Each commission had two commissioners (one British and one American) who, together with a secretary, constituted the Board of Commissioners. They met at least twice a year to determine what exploration work and surveys were to be carried out and, eventually, to hear and to decide, in their capacity as judges, the arguments for the prospective boundaries. There were also two agents to acquire the data and evidence for their respective nation’s case and to present it to the Board of Commissioners. Although the commissioners and agents went into the field from time to time, two surveyors led the on-site crews in the real work of exploration and mapping.

James Gambier, 1st Baron Gambier, the head of the British delegation in 1814, said he hoped that the Treaty of Ghent would bring a lasting peace. His American counterpart, John Quincy Adams, replied that it was his wish that “it would be the last peace treaty between Great Britain and the United States.” Thanks to the eventual resolution of the eastern boundary controversy, so it proved to be.

The Islands in Passamaquoddy Bay

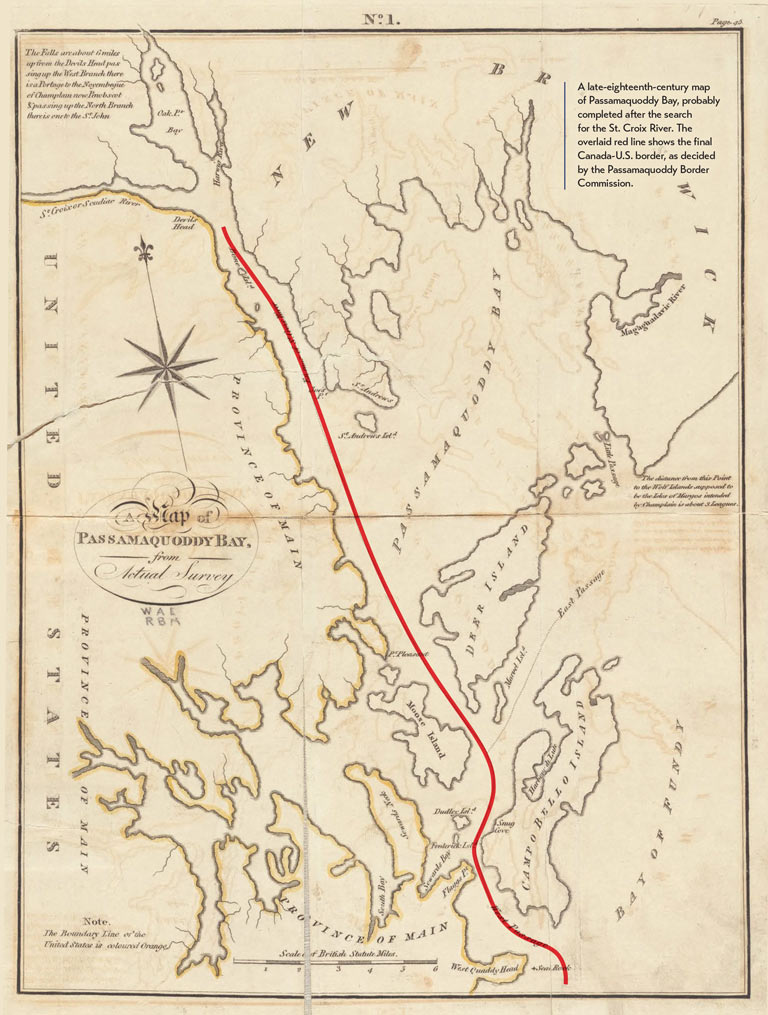

The Passamaquoddy Commission was charged with deciding who had claim to the islands in Passamaquoddy Bay, an offshoot of the Bay of Fundy squeezed between the west coast of New Brunswick and the east coast of Maine.

During extensive talks before the War of 1812, the United States had offered to give up claims to a number of these islands. So it was not too difficult, upon examination, to work out an arrangement where the islands closest to the American shore and with American citizens on them — Moose, Dudley, and Frederick islands — were deemed to belong to the United States, while the larger islands — notably Deer, Campobello, and Grand Manan islands — were held to be British.

A successful decision was agreed upon by British Commissioner Colonel Thomas Barclay and U.S. Commissioner John Holmes in late 1817, with the Boston Gazette commenting that the affair had been resolved “in a most amicable and satisfactory manner.”

Advertisement

The New Brunswick-Maine Border

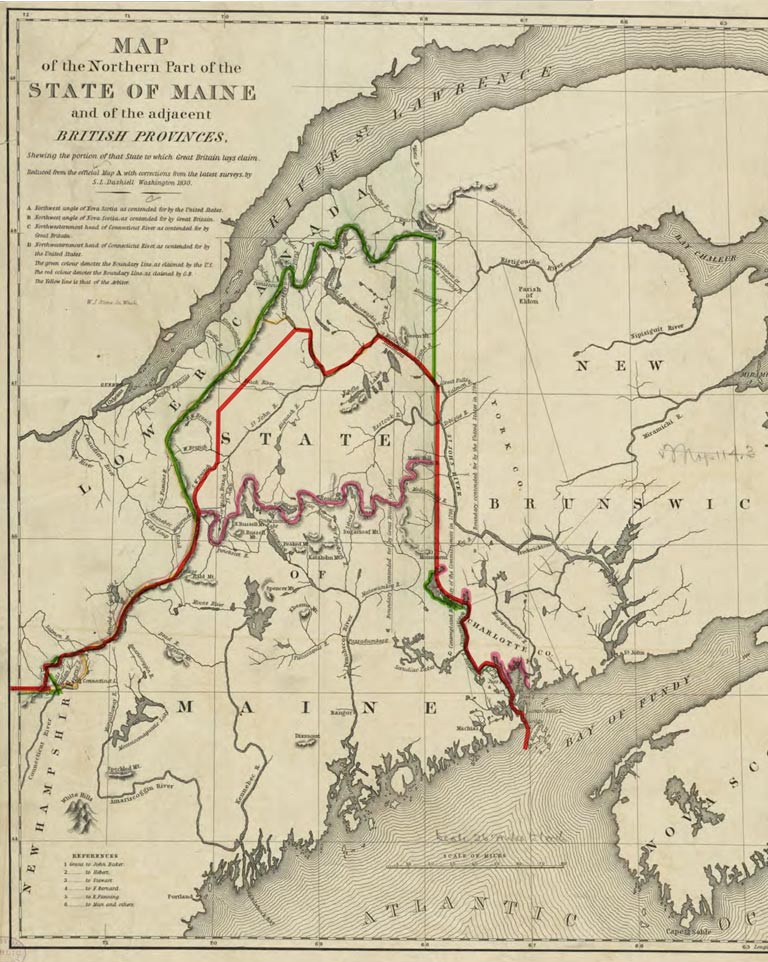

Under the Treaty of Paris, the border between New Brunswick and Maine would follow the St. Croix River to its source and, from there, extend due north to “the Highlands ... which divide those Rivers that empty themselves into the River St. Lawrence, from those which fall into the Atlantic Ocean.” The border would follow those highlands westward to the source of the Connecticut River, then it would cut due west along the forty-fifth parallel until it hit the St. Lawrence River.

In 1817, a small party with the two chief surveyors, the Quebec-born Colonel Joseph Bouchette and the American John Johnson, set out in an attempt to apply the description in the treaty to the facts on the ground; but this proved easier said than done. Upon reaching Mars Hill, about eighty kilometres north of the source of the St. Croix River, Bouchette declared that they had found the “Highlands” of the treaty. Not so, countered Johnson: In his opinion, the “Highlands” lay more than 150 kilometres further north, at the source of a small tributary of the Restigouche River.

To make matters even worse, when the teams surveyed the forty-fifth parallel, they found that it had been wrongly surveyed in 1772, putting American villages and settlements on the British side of the border and, most embarrassingly, leaving the newly constructed U.S. fort at Rouse’s Point on Lake Champlain almost a kilometre into British territory. Perhaps it is little wonder that, by 1822, British Commissioner Barclay and American Commissioner Cornelius P. Van Ness were unable to agree upon the boundary line.

In the event of such an impasse, the Treaty of Ghent provided for “a friendly sovereign” to decide between the two claims. King William I of the Netherlands was chosen, and in January 1831 he decided upon a compromise that divided the disputed territory roughly in half: The boundary he proposed would run from a point on the St. John River, along that river to the St. Francis River, and then along the highlands to the New Hampshire border.

However, this compromise was rejected by interests in Maine and Massachusetts, and eventually by the U.S. government, on the grounds that the king had to decide in favour of one claim or the other. The matter would remain unsettled for another decade.

The St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes

Tasked with drawing a line through the middle of the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes — and with divvying up the islands that fell on that line — this commission’s work parties spent several summers canoeing through those waterways, all the way to Sault Ste. Marie, at the eastern tip of Lake Superior. But, as time and expenses mounted, the U.S. Congress began to rebel.

The commissioners were each paid a yearly salary of £1,000 sterling, or $4,444. This was a lot of money at the time, and the other specialists — agents, surveyors, and secretaries — were also well-paid. In 1820 alone, the expenses for the American portion of this commission added up to $161,548 (or roughly $ 4.4 million in today’s dollars), provoking Congress to reduce the salary of the U.S. commissioner and agent.

In 1819, in the marshy areas of western Lake Erie and the Detroit River, a sickness struck that “effectually disabled the united Commission,” Bigsby wrote in The Shoe and Canoe. “Scarcely a man escaped either ague or bilious remittent fever under severe forms.” Illness claimed the lives of British Commissioner John Ogilvy and of two additional members of the British party.

“The distribution of the very numerous and often fertile islands caused great labour in soundings, measurements, and valuations,” Bigsby wrote. Nevertheless, by late 1821 and January 1822, with extensive maps completed, both American Commissioner General Peter B. Porter and the new British Commissioner Anthony Barclay — the son of Thomas Barclay, commissioner for New Brunswick and the Passamaquoddy islands — were able to compromise in allocating the islands in the St. Lawrence and Detroit rivers. With the approval of their governments, these commissioners reached an agreement in June 1822.

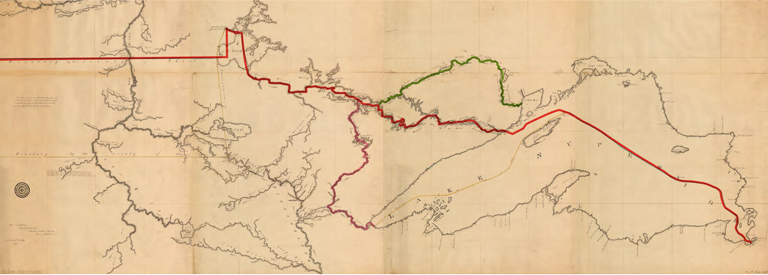

Sault Ste. Marie To Lake of the Woods

In many ways, this was the most difficult section of the border to settle. Travel from Montreal or New York City to the region beyond Lake Superior took almost two months, even using steamboats part of the way. To save time, the American surveyor James Ferguson and much of his crew wintered in 1822–23 at the Fort William fur-trading post at what is now Thunder Bay, Ontario.

While Lake Superior was a hazard, the region beyond it was rugged wilderness, consisting of exposed bedrock, rapidly flowing streams, impenetrable swamp, and forest. While well-travelled by Indigenous people and fur traders, the region was so remote that almost no U.S. or Canadian government official had visited it.

Beyond the western end of Lake Superior, according to the Treaty of Paris, the boundary would follow an unnamed waterway to the “Long Lake” and continue along another unnamed waterway to Lake of the Woods. The different routes from Lake Superior to Lake of the Woods led to a disagreement as “unexpected as it is unpleasant,” U.S. Commissioner Porter wrote to the U.S. secretary of state in 1820. Porter was convinced that Commissioner Barclay was “under specific instructions from his government” to make sure the border benefitted the Canadian fur trade.

The British surveyor was David Thompson, a famous explorer and map-maker who spoke Cree and Blackfoot. For the route from Lake Superior to Rainy Lake — which both parties agreed was the “Long Lake” — Thompson proposed the St. Louis River, which empties into Lake Superior at the present site of Duluth, Minnesota. But the Americans argued for the more northerly Pigeon River — or for the Kaministiquia River, which lay even further north.

At one point, it seemed that the Pigeon River might emerge as a compromise — and, indeed, this eventually became the border. But, at the time, the two governments refused to approve it. Thus, in 1827, the commissioners closed their proceedings and reported that they could not reach an agreement.

The boundary commissions produced what were perhaps the best maps, for the time and for decades after, of the borderlands between British North America and the United States. But, after years of work, two of the commissions — those tasked with the New Brunswick-Maine area and the region from Lake Superior to Lake of the Woods — had failed to agree on borderlines.

Negotiations in the 1830s proved fruitless, and threatening tensions flared along the New Brunswick-Maine border; but a change of governments in both Britain and the United States in 1841 created a climate for high-level negotiations. Lord Ashburton, appointed by the British government, and U.S. Secretary of State Daniel Webster met in Washington in the summer of 1842 ready to compromise. Using the boundary commissions’ maps, they agreed on borders and formalized the agreement in the 1842 Webster-Ashburton Treaty.

Ashburton wrote to Webster in 1843 that he believed “the treaty was a good and wise measure, and good and wise because it was fair.” Despite his assessment, the boundary commissions had neglected to consult one important group of people: the First Nations whose territories spanned the borderlands. Notably, the newly drawn border ran smack through the Mohawk community of Akwesasne — located on the forty-fifth parallel where the St. Regis River empties into the St. Lawrence River. Today, the community continues to straddle the international frontier, and members of the Mohawk Nation of Akwesasne possess dual Canadian and American citizenship.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Canada's History magazine was established in 1920 as The Beaver, a Journal of Progress. In its early years, the magazine focused on Canada's fur trade and life in Northern Canada. While Indigenous people were pictured in the magazine, they were rarely identified, and their stories were told by settlers. Today, Canada's History is raising the voices of First Nations, Métis and Inuit by sharing the stories of their past in their own words.

If you believe that stories of Canada’s Indigenous history should be more widely known, help us do more. Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share Indigenous stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement