A Brief History of Trees

In 1836 an unhappily married woman named Anna Jameson took a ramble through the New World. When it was over she did what most travellers to Canada did—she wrote a book about it.* This work, which has entered the Canadian canon and become a classic, contains a frequently quoted sentence: “A Canadian Settler hates a tree, regards it as his natural enemy, as something to be destroyed, eradicated, annihilated by all and any means.”

In fairness to Mrs. Jameson, Canadian settlers were definitely not tree huggers. They had their own attitudes toward trees and they had their reasons for having them. By 1822 the Military Settling Department had determined the tree to be a leading cause of death. “Drowned,” “deceased,” and “killed by a tree,” were fingered as the great culprits of Canadian depopulation. The first, of course, was “gone to the States.”

Often, as happened to the Reverend John Scadding, the tree fell on you. More typically the axe-head bounced and cleaved a foot or leg, leading to the most frequent injury in Canadian medical history: the chopped limb. Menard, a Jesuit and one of the first white men to reach Lake Superior, had a tree fall on him while paddling a canoe. In the timber camps of the 1920s, lumbermen stricken by typhoid and diphtheria were typically carried out in the blankets they died in, and buried in a ditch. Sometimes they had a tooth pulled by a camp dentist, and died of infection. There were countless ways to be killed by a tree. Even the Iroquois Book of Rites, which predates Columbus by half a century, tells of an axe that will have survived wild beasts, thorny ways, and … falling trees.

Most famously, death by trees comes in the form of fire. There is barely a town, settlement, ship, or even a lighthouse in the Dominion that did not burn to the ground or waterline at least once, and often twice. One of the first ordinances passed in English Canada was a law requiring homeowners to keep a pail of water on the porch at all times. When Toronto burned to the ground for the second time, wood, as a building material, was outlawed in favour of brick. Vancouver was destroyed by fire in 1886. Ottawa burned twice, and even the mill that sawed the boards that built Ottawa burned four times. The mining town of Cochrane, Ontario, burned three times. In the 1916 fire, more than two hundred people lost their lives. An equal number, caught out in the backwoods, are also believed to have died. Ships on the Great Lakes, blinded by smoke from forest fires, have plunged against rock shores and wrecked.

article continues below...

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Some of the fires that ravaged the eastern pineries blotted out the sun for days. These were the “crown fires”: they would explode the crown of one tree, race down its trunk to the bush floor, and go after the next one. It didn’t help that logging practices of the day left only one-third of every tree behind, making the forest floor a tinderbox. Over it, the great fires moved at almost thirteen kilometres an hour, hopping over bodies of water as wide as the Ottawa River. Some fires stretched more than a hundred kilometres across, with fuelled by the rich resins of the pine shooting up forty-five metres into the air; dirt itself was known to ignite.

A 1948 forest fire that swept Lake Superior’s north shore generated so much smoke that streetlights had to be turned on at noon as far away as Texas. In fact, it is not unknown for smoke from Canadian forest fires to reach England. The Great Miramichi fire of 1825, in New Brunswick, has been called “the most dreadful conflagration ... in the history of the world.” At least 160 people died in it. It stretched 112 kilometres on either side of the Miramichi River, and caused winds of such velocity that salmon were sucked out of the river and scattered in the trees.

Given this grim history, it is perhaps not surprising that Canadians were ambivalent toward trees. For Christian settlers there was a much deeper reason to distrust trees: Christ was crucified on a tree—a trembling aspen. The very reason the aspen trembles, wrote essayist Thomas De Quincey, is because it knows Christ was murdered on its back.

Mixing trees with religion is a long and honoured tradition. Indigenous gods blow on trees to make them grow. In the past, skilled First Nations are believed to have routinely made a rope of willow branches and lassoed the moon. To the poet, the breath of God does not just sigh in the trees, it soughs. This delightful Anglo Saxon word pronounced either “sows” or “suffs” originates from the lost verb swogan, “to sound.” Grey Owl, the world’s most famous pretendian and Canada’s original conservationist, called this the sound of trees “praying to be saved.” In what is perhaps the first ecological manifesto written in Canada, Grey Owl pinned a note to a tree that said, “God made the forest for the animals. Don’t burn it up and make it look like hell.”

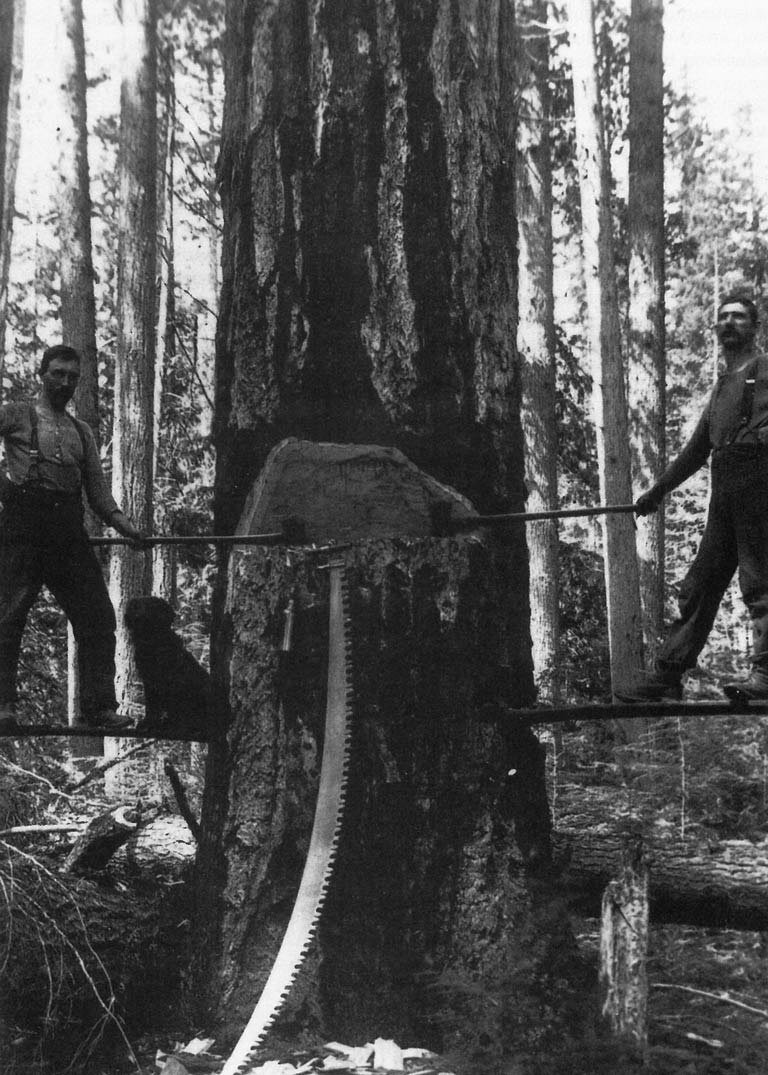

In pioneer times felling large trees was not easy. John Galt once discovered an oak tree in southern Ontario that was more than ten metres in diameter, with branches that started twenty-four metres above the ground. He speculated the only reason it remained alive was because “there was not yet a saw in Canada long enough to cut through it.” The beech trees of Christian Island, Ontario, were once so large they had to be drilled and brought down with dynamite before being fitted into a sawmill. Today the Sitkas of British Columbia are sometimes flown out, individually, by helicopter.

For many years, it was said and believed that the Canadian forest stretched to infinity. Even those who should have known better, such as economist Stephen Leacock, described with confidence the “trees flowing in from the inexhaustible northern backwoods.” In writing the timber barons predicted two hundred years of full cutting in Ontario and Quebec. Arguably, they got forty. In that time, from about 1870 to 1910, the largest piney on the planet was cut down and shipped east on a hundred different rivers. It was an act that staggers the imagination, cost the lives of an untold number of men, and was perhaps as grandiose and labour-intensive as the building of the great pyramids of Egypt or putting a spaceship on the moon.

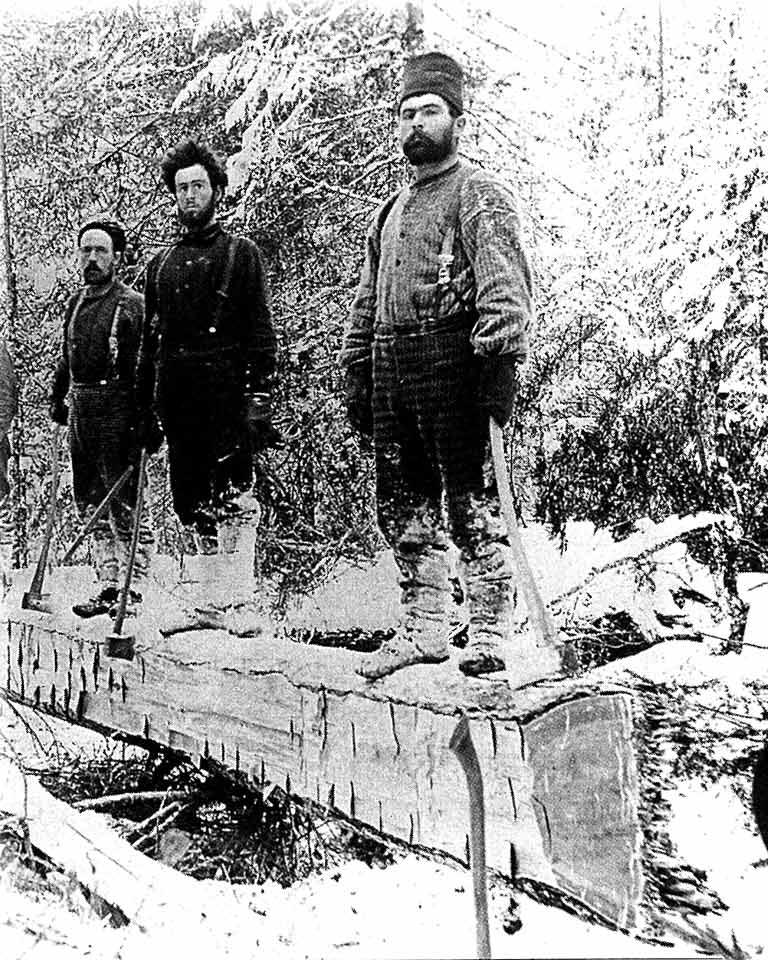

In those brief years there appeared on the earth an apotheosis of wood, a technology based on trees which today is almost impossible to imagine. When rivers were insufficient for transporting logs, artificial rivers—timber slides—were built above ground. These structures sometimes ran sixty-four kilometres. The men who built them lived in shanties constructed of the trees around them. Watertight scoop roofs were made from halved logs. Door hinges were carved from pine. Nails to hold wood together were made from wood. Timber trains ran on rails made of timber. Fully half the men in Canada were employed cutting down trees.

An entire country sprung up based on the removal of trees; pine trees in particular. This industry within a country soon developed its own history, its own code of ethics, a repertory of song, of poetry, even its own language. Some of the more renowned examples of timber jargon surviving today are “jackpot,” the heap of filthy clothing the timbermen left behind them at the end of the season; and “bushwhacker,” an itinerant timberman who moved from camp to camp, spreading lice. The term widow maker has its origins in the Canadian bush where it describes a dead but standing tree; also known by the French-Canadian word chicot, which corrupted into checko, a term still heard to describe a large stump.

The insularity of this language is sounded in the following exchange between an injured timberman and a nurse. The timberman, a man named Happy Murphy (apparently it was de rigueur for all timbermen to have nicknames) is asked by the nurse how the accident happened. He replies,

“Well you see, I was the skyman, and we were shy a grounder, and there was a gazabo come down the pike and the push took him on. The first thing he sent up was a big blue butt, and I yelled out to him to throw a Sagamaw into her, but the S. crollexed her, and then he gunned her, and she came up and cracked my stern.”

“I don’t understand,” said the nurse.

“I don’t either,” interrupted the top loader. “I think he must have been bughouse or jigrood.”

Behind such displays of rhetoric lay the elimination of the North American forest. By 1890, Wisconsin was practically denuded of trees, and American timber barons were buying up timber rights in Canada—where the policy of “cut out and get out” was in full swing. By 1920 the spoliation of the Lake Superior forests was complete. Stumpage fees were neither collected nor assessed, and the trees often went straight into American mills.

Arguably one of the first attempts at timber management undertaken by the Canadian forest industry occurred in 1865 when assassins were hired to murder E. Pauline Johnson’s father, the forest warden who resolutely guarded the trees of the Six Nations reserve. By the early twentieth century, the industry was so corrupt that Port Arthur, Ontario, became known as “the place where they manufacture affidavits.” When the Ontario Temperance Act came into effect, and it was no longer possible for hotel owners to make a killing in liquor, they found it an easy move into timbering.

By 1919 the “timber thieves” had created such havoc that the Riddell-Latchford commission was appointed to investigate. A timberman accused of cutting trees on private property offered the intriguing defence that trees belonged to God, therefore he could do what he wanted with them. When a piling and pulpwood operator was asked by the commission what he would do if he saw timber growing on land, he answered at once, “I’d wheel right into her.”

Wheel right into her, indeed. J.R. Booth, owner of the largest mill in the world, took out of the Algonquin area a million trees a year, and did not plant a single one in return. His mill at Ottawa churned more than three hundred thousand meters of board every shift. The largest sawmill in the United States at Duluth did not produce that much lumber in a year. A century after Philemon Wright had guided the first crib of pine trees down the Ottawa River in 1807, the cry was already ringing through the great eastern pinery: “Crooked trees make straight dollars, boys. Cut them down!”

Advertisement

By 1922 the Riddell-Latchford commission wrapped up its investigations with a series of recommendations that were ignored. In 1925 J.R. Booth transported the last squared timber out of eastern Ontario and then, at the age of ninety-three, died. The great pineries of eastern Canada were gone.

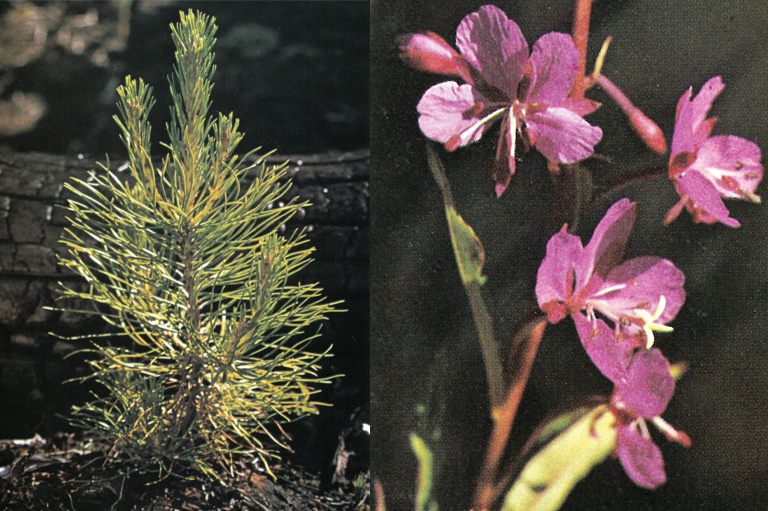

In western Canada it was a different story. There the compulsion to rid the land of trees was replaced by an equally potent urge to plant them. To the European, arriving in a land without trees was a second form of exile—the first one being from the biblical garden that trees symbolized. What followed in the West was an effort to reestablish Eden on a treeless plain. The apple tree was preferred: it was the first tree in the first garden, a potent Christian symbol, a good food source, and planting them was considered an act of faith and permanence (an apple tree can take years to yield). The first apple trees to reach the Okanagan Valley were planted by a Catholic priest. Father Charles Pandosy, in 1862.

Generally, apple trees were planted by the hundreds of thousands without success until the Saunder’s Hybrid proved capable of surviving the cold Canadian winter. The planting of trees became a moral passion. In the nineteenth century, a special “Arbor Day” was “set apart and consecrated” in the U.S. and Canada for the plan ring of trees.

We form our sense of space in relation to a tree. In southern Ontario, a mature hardwood is the size of a three-storey house. Its mantle fans over the roof in summer, and provides a windbreak in winter. Many of the neighbourhoods of North America are arranged on this principle.

Whether we know it or not, trees are a standard for judging distances. The visual standard set by trees accounts for the disorientation experienced on the prairies: the sense that things look closer than they arc. In the Arctic, where the tree is replaced by the rock, the feeling can be reversed: points that seem for away, are closer. Near the Arctic Circle I heard an Inuk woman boast of being “down South.” Curious as to how far she’d managed to get, I asked her. “Whitehorse,” she said. When I suggested Whitehorse might not qualify as “down South” she laughed at me. “Of course it does. They have trees there and everything!'”

Trees define the strength of this continent just as the removal of trees defines its deterioration. Henry David Thoreau, in a passage almost too cruel to read, once described an axe head cleaving into a tree trunk as though it were an assault on the human body. When John Galt cut down the first tree at what is now Guelph, Ontario, he observed, tellingly, “the genius of the Woods departing this place forever.” Author Malcolm Lowry’s favourite tree outside Vancouver was cut down in order that a small pan could be used to build a violin. Incensed, Lowry pinned a note to the stump: “Would you like this to happen to you, you pig dog? When you hear your lousy fiddle it will make a noise like slaughtered birds.” According to Oliver Wendell Holmes the best poems he ever wrote were the trees he planted on the banks of the Hoosatonic River in Massachusetts. The painter John Constable embraced trees the way he embraced children. Emerson hoped that all the pages of his books would bear the smell of pine.

It would seem that in our deepest imagination the tree constitutes a human being. When John Galt and his party felled that maple at Guelph “there was a funereal pause as when a coffin is lowered into the grave.” The killing of trees creates outrage, and the planting of seedlings is hailed as virtuous. The conflict resonates throughout the language of timbering. According to the industry, trees are “harvested.” But the term has not stuck. Trees are “felled,” “cut down,” “chopped down,” the language of warfare; the warrior “falls” in battle, men are “cut down” by machine-gun fire.

Whether it be the Tree of Life, painted fifteen thousand years ago on a Canaanite Megiddo vase, the tree of knowledge, the inverted tree or the Cabala, the Iroquois Tree of Peace, or the Green Man mythologies that reach back to the last Ice Age, trees are rooted so deeply in us that it is difficult to know where the tree ends and where the human begins. According to Pauline Johnson, her parents resolved their squabbles by walking along the hardwoods of the Grand River — the first known example of a successful couples therapy performed by trees. These massive maples, elms, walnuts, and oaks were, in her words, “the imperial trees ... voiceful and kingly.” Here is signalled the familiar notion of the tree as natural king. The white pine has long been called “the Monarch of the Forest.” Trees have “crowns.” For centuries we have attributed wisdom to them. Christ may have been crucified on a tree, but the Buddha became enlightened while sitting beneath one.

Save as much as 52% off the cover price! 6 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital.

The study of trees is known as dendrology. The tree, according to Morton and Lewis, is “a single stemmed perennial woody plant growing to a height of more than 10 feet.” Trees, like people and animals, migrate. Spruces, larches, birches, poplars, and willows sweep quickly across a continent. Oaks, the walnuts, the butternuts possess heavy seeds and require animals to move them, hence they travel slower. Regardless of their speed, all trees, according to Vladimir Nabokov, “are pilgrims, all trees in the world are journeying somewhere. They have their Messiah whom they seek.” Perhaps that Messiah lives in Toronto which occasionally calls itself “the City of Trees.”

There are approximately 130 local species of trees in North America. Each of them possesses its own Book of Wisdom. This wisdom was accumulated over many centuries by the First People who, fortunately, were willing to pass it on.

When Cartier arrived on the shores of North America in the 1530s with half his crew dying of scurvy, the Stadaconans supplied them with the boiled young twigs of the red spruce mixed with maple sugar and then fermented. The knowledge that this concoction cured scurvy could not have come easily. Untold years of trial and error were needed to discover whether the young twigs, not the mature ones, did the job, or that maple sugar and not sturgeon eggs was required for the concoction to work.

That the First Peoples possessed such knowledge was recognized early on by the Europeans who witnessed them extracting syrup from the maple tree as early as the 1600s. In 1824 Reverend William Bell, in his book Hints to Immigrants, advised using trees as a cure for being lost: “Large trees have always moss on the north side and the largest limbs generally on the south.” According to Bell, Indigenous people steered their way through the woods by following the longest branches of the birch tree, “which are said to point eastward.”

It would not take long to observe them using the white ash to relieve the itching of mosquito bites, or to learn that the roots of the eastern cottonwood were excellent for creating friction fires. South Ontario settlers were soon using dried beech leaves to stuff mattresses because it was springier than straw. Canadian pine, it was discovered, does not warp and gutter in the rain, which made it perfect for the masts of sailing ships and the windowsills of houses. In the absence of writing paper, French explorer La Hontain took to inscribing his notes on birchbark. For the constipated, the white walnut tree provides a soothing laxative. The inner root of the tulip tree makes an excellent heart stimulant, although it is not clear how this connection was made, or by whom. The same can be said of the witch hazel, which is used to divine water. Rope was made from the hackberry tree, ink from the pin oak. Arrow shafts from the western snowberry, bows from the yew and ash. The acorns of the white oak can be eaten, the oil extracted from it soothes painful joints. Rocky Mountain juniper was found to be excellent for the manufacture of pencils, the black willow for polo balls. The letters in Gutenberg’s printing press were carved from beech. And on it goes.

Perhaps the Vikings had the final word when they insisted the world was held together by a tree: the ash tree.

By 1860 southern Ontario was almost void of trees. Anna Jameson’s tree-hating (and penniless) Canadians had chopped down everything in sight and burned it. A contemporary, Samuel Strickland, once described the countryside of southwestern Ontario lit up night after night by as many as two hundred brushfires. The ash from these burnings would be rendered into potash, a cash crop, and sold to England to make soap. Perhaps in uttering her famous comment, Jameson was unaware that the government of Upper Canada demanded settlers clear a certain acreage of trees each year or face having their land repossessed.

After spending barely a year in the New World, during which time she made unflattering comments about the Irish, inaccurate and problematic observations about First Nations people and condescending remarks about Canadian settlers, Anna Jameson concluded that “the people here are in great enthusiasm about me,” then returned to England, where she wrote books about art, and died in 1860.

Five years later, paid assassins attacked Pauline Johnson’s father, the officially appointed protector of the “imperial” hardwoods of the Grand River. Attacked again a decade later, he finally died in his own bed beneath the oaks and the walnuts that suffed and soughed outside his window. He was just one of many who were killed by trees. He died not for his hatred of them, but for his love and his devotion. He was one of many martyrs who have given their lives to this complex and barely understood religion.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement