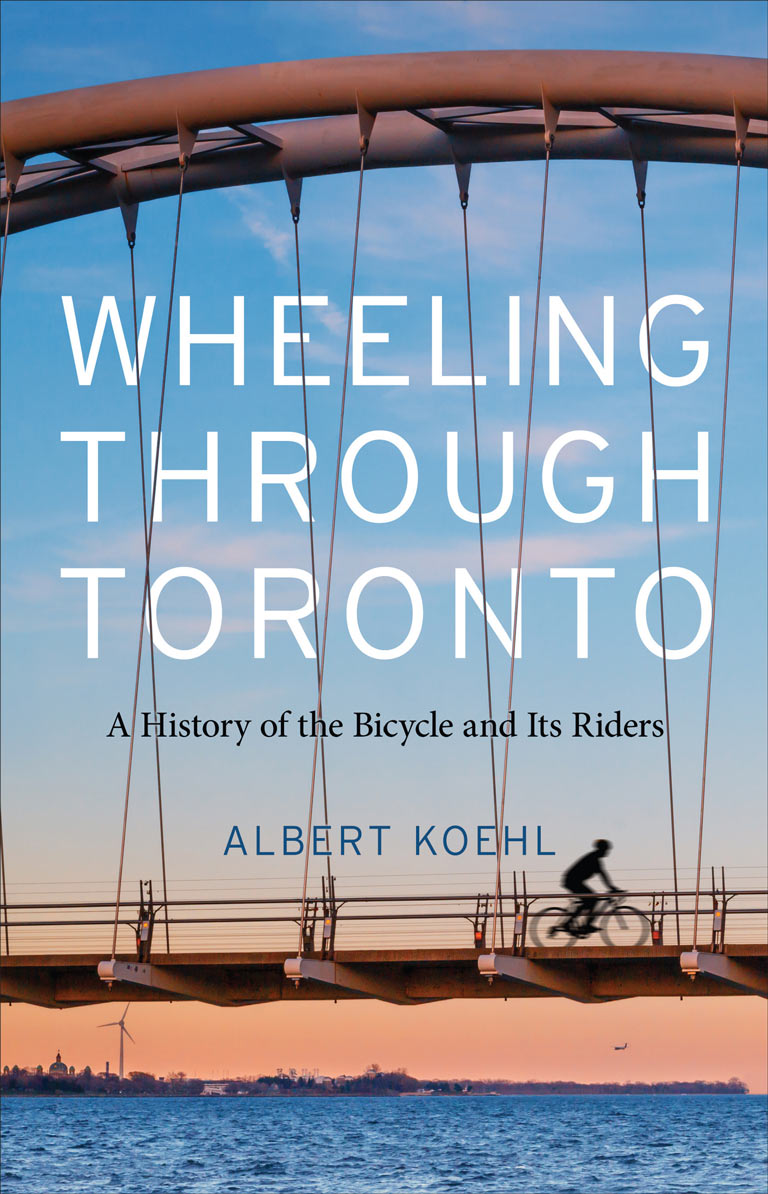

Wheeling through Toronto

Wheeling through Toronto: A History of the Bicycle and Its Riders

by Albert Koehl

Aevo UTP

441 pages, $29.95

On the same day Toronto City Council held a meeting to discuss Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s desire to remove bike lanes on Bloor Street, University Avenue, and Yonge Street, I went shopping for a used commuter bicycle.

It wasn’t an act of protest. I’d been devouring Albert Koehl’s book Wheeling through Toronto and was reminded that, for many reasons, pedal power makes sense. Whether for grocery pickup or a leisurely Sunday along the fifty-six-kilometre Martin Goodman Trail, it’s an essential vehicular tool in the big-city resident’s kit. But I’d never ride a bicycle to work unless, like the Dutch, the city built a network of fully-protected lanes — it’s hell out there.

Koehl, who begins our journey during the bicycle craze of 1896 — the safety improvements of equalsized wheels and a chain drive having turned the bicycle from a novelty, the penny farthing, into a popular invention — tells us that even then bicycle paths weren’t respected: “Cycling groups were quick to push for enforcement, especially on the popular Kingston Road cinder path, where farmers often parked their wagons, before going to nearby hotels.”

Things did not improve when the automobile arrived on Muddy York’s roads. By then, writes Koehl, bicycles had come down in price and had “graduated … from being merely a plaything for the rich to a useful tool” for average citizens, messengers, the police, and delivery people. While early adopters of the horseless carriage understood their “low rank on the road” — in 1910 there were only 2,000 cars in Toronto — by 1929, when there were 120,000 cars, newspapers had a field day reporting on the “menace” to the lives of pedestrians and cyclists.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Koehl describes the bicycle’s unfortunate demotion by the media to a mere child’s toy (in the 1930s the vehicle had indeed become very popular with children), which relieved “City Hall from any obligation to accommodate cyclists on roads,” as well as its brief return to the adult spotlight during the Second World War. The rise of suburbia and the creation of Metropolitan Toronto in 1953 brought their own challenges — as car culture became more entrenched, “contrary voices were difficult to hear.” This trend continued until the sea change of the early 1970s, when a “bicycle revival was in full swing.”

Why the cycling renaissance? Koehl suggests that it stemmed from the confluence of the “sexy and cool” ten-speed bicycle, the gas crisis, the counterculture’s rise, the election of Mayor David Crombie (who refused to widen roads or cut trees to accommodate more automobiles), and the death of the Spadina Expressway under Premier Bill Davis. Between 1970 and 1975, Bloor Cycle, a popular retailer, “reported a sales increase of 400 percent.”

Despite this, there was still an infuriating lack of infrastructure in downtown Toronto. Study after study had been commissioned, including a utopian vision of a 160-kilometre network of bike “freeways” in the 1960s. But by 1979 the 80 kilometres of existing trails were buried in the city’s ravines or hidden in parks, because the prevailing approach was to try to get bicyclists off roads. If for some reason cyclists had to use the road, they would be considered vehicles: Riders were expected to integrate into the flow of traffic, use the left-turn lane, and take their chances. Called “vehicular cycling,” the approach was gaining popularity in the United States.

Advertisement

The City of Toronto finally built its first bike lane in the summer of 1979, albeit on a windy, one-way street called Poplar Plains Road. Koehl writes that, despite being only six hundred metres in length, the lane “traumatized” the Toronto Star due to concerns over safety and heavy traffic.

By 2019, according to Koehl, Toronto was again “becoming a city of cyclists, even if it was still a long way from being a city for cyclists.” His frustration at the miniscule inventory of bike lanes practically jumps off the page, and he reaches back to the 1980s and 1990s to try to understand what kept cycling “subordinate … in the transportation hierarchy.” Was it bureaucracy? Vehicular cycling? Piein- the-sky plans with no real budget to implement them? The yo-yoing of political attitudes?

No matter. Albert Koehl, an environmental lawyer and a cycling advocate, is a good and thorough storyteller. He covers not only the politicking but also the 1899 birth of bicycle manufacturer CCM in what is now the Toronto neighbourhood of Weston, the years of bicycle licences (originally implemented to curb theft), and the rise of speed limits for automobiles. He also profiles characters such as avid early adopter Dr. Perry Doolittle (1861–1933) and Hilda Tiessen, who co-founded Sunwheel Bicycle Couriers in 1979.

Can a good story about two wheels, and the cycling ghosts it conjures, be enough to put a dent in Toronto’s love of the automobile? That’s still a good question.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!