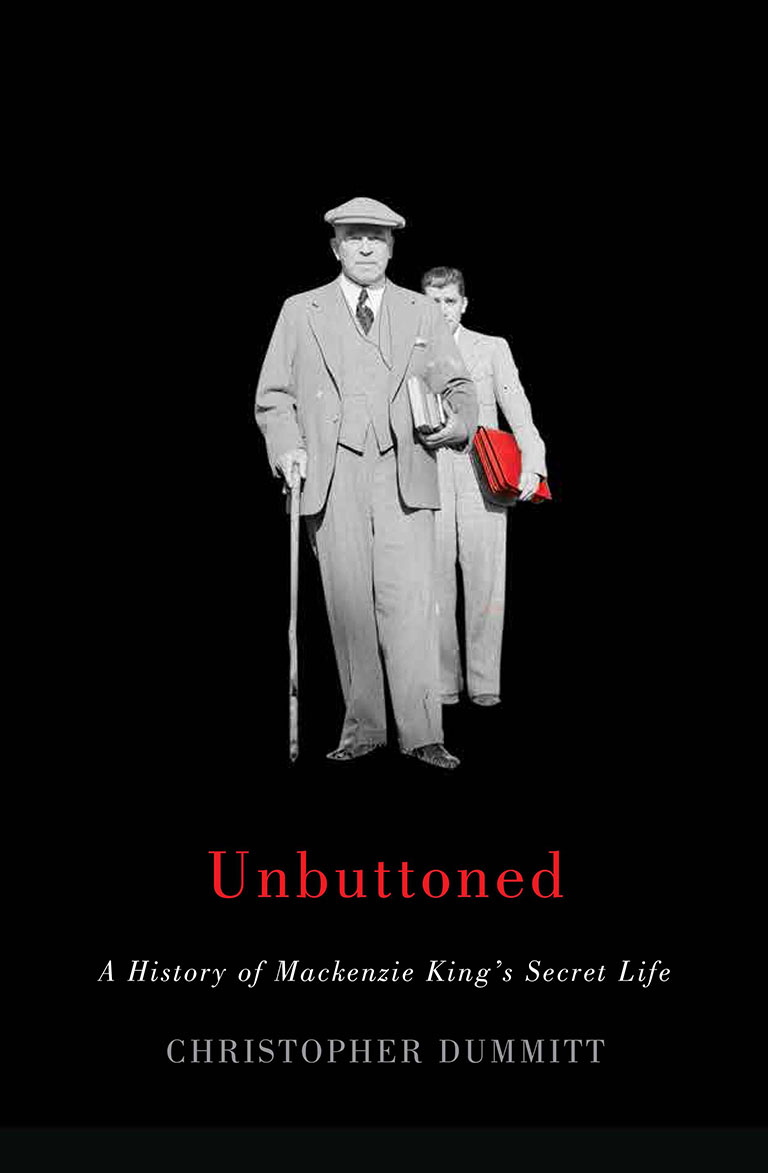

Unbuttoned

Unbuttoned: A History of Mackenzie King’s Secret Life

by Christopher Dummitt

McGill-Queen’s University Press, 341 pages, $34.95

Christopher Dummitt has written a fascinating book on the Mackenzie King diaries, and in doing so he has also provided much insight into King and the history of his reputation. The diaries, now readily available online, were written on a regular basis by Canada’s longest-serving prime minister from a very early age. They are a record of King’s thoughts, fears, prejudices, and daily expenditures, and they give us invaluable insight into his character and personality as well a chronicle of his age.

Dummitt’s focus is the saga of the diary itself. William Lyon Mackenzie King never intended that his daily log would become a public document. Indeed, he gave clear instructions in his will that the document should be destroyed by his executors. This never happened, because Norman Robertson, Jack Pickersgill, Fred McGregor, and Kaye Lamb quickly realized on King’s death in 1948 that this daily record was too valuable a public document to be allowed to succumb completely to King’s private wishes.

Yet, at the same time, the executors were determined to control what could be seen and what could be said about the diaries, an exercise in control and censorship that soon led to real battles. King’s diary was not, they discovered, just about public events. It also touched upon his personal thoughts and predilections, including, most notably, a lifelong interest in spiritualism. His participation in seances — efforts to reach his mother and other relatives “on the other side” — were known to his assistants and aides at the time and feature at many points in the document. The issue soon arose of what to do about the diaries’ “personal side.”

The bureaucratic culture of the time was one of great secrecy — and Dummitt insightfully describes the tensions around the clash between this culture and the demands of the academic community for greater openness and candour about the iconic document. Pickersgill, assisted by young academic Donald Forster, brought out volumes of The Mackenzie King Record, but these were carefully edited and were subsequently criticized for not showing the whole story. As time went on, more researchers insisted on greater openness and accountability, at times to their own detriment. Eventually, after many years, the decision was made by the executors to allow access to the entire diaries — except for one missing volume and a notable decision to burn an additional set of papers that were said to be “strictly personal” and “purely spiritual reflections.”

At the time of his death King was widely seen as a truly remarkable politician and statesman. The fear of his executors was that a full disclosure would lead to a series of attacks on his reputation. The first expression of this was a Maclean’s magazine piece by Blair Fraser on King’s trips to a spiritual advisor in London. This was followed by a critical analysis of King by H.S. Ferns and Bernard Ostry, based on the premise that King’s involvement with the wealthy Rockefellers made him an enemy of working people, rather than their friend.

Charles Stacey’s revelation of King’s tortured sexual experiences, entitled A Very Double Life, was exactly what the executors feared would happen. Colonel Stacey, a soldier and military historian who had a very negative view of Canada’s wartime leader, found what he concluded was proof that King consorted with prostitutes and led a double life. A more balanced view would be that King was never fully comfortable with his sexuality and that the particulars of his sex life remain uncertain. Stacey’s portrait of King was unflattering, to say the least.

We are now at a point where warts and all is the order of the day. The diaries don’t tell the whole story, not because they are incomplete but because no diary can tell the full impact of an individual on the events of his time. We know that King was an appeaser and had a completely unrealistic view of Hitler, as the diaries reveal; but we also know that King was an effective, if exasperating, leader of a country prone to division and deep sectarian quarrels. The self-centred fussiness revealed by the document does not do justice to his public achievements.

It is fascinating to see the difference between our own historical culture and that of our neighbours to the south. In the United States, no month passes without a new biography of leaders whose lives have been analyzed over and over again. Here, we are lucky to see more than a few in a decade. Narrative history struggles to stay alive in Canada, and Dummitt’s account of the ups and downs of King’s diary and his reputation is a welcome sign of vigour and life in Canadian historical scholarship.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement