Trudeaumania

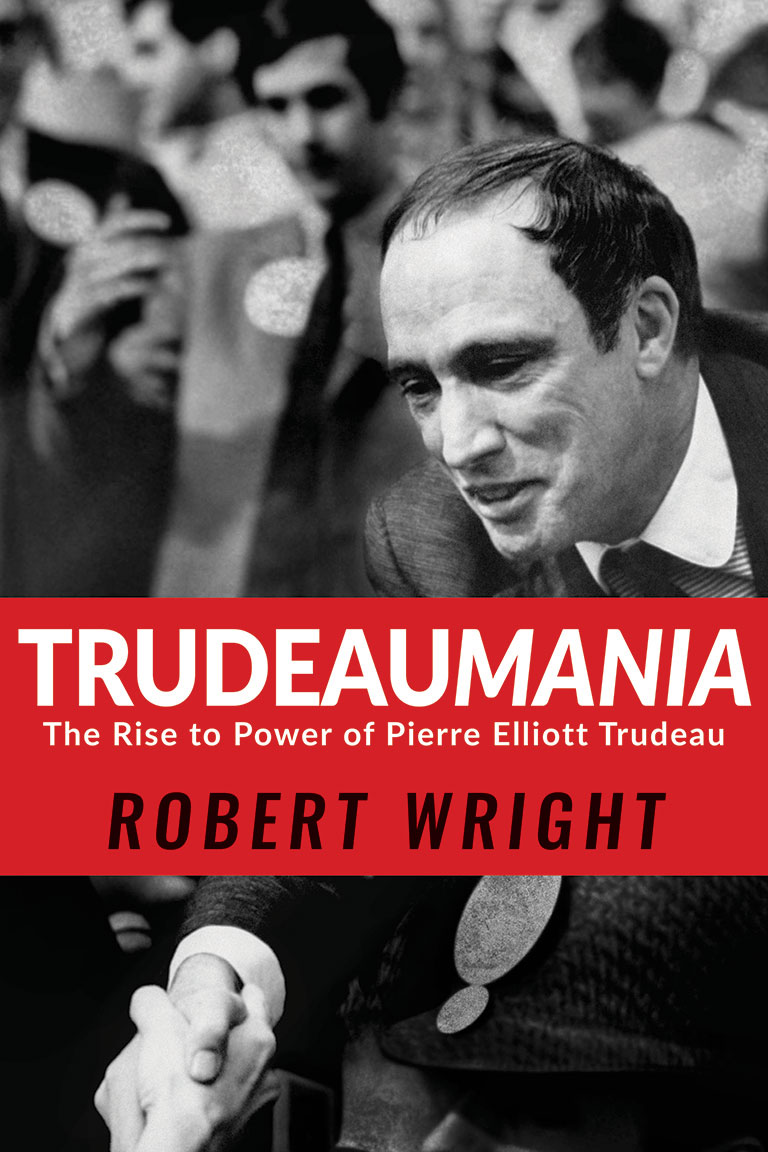

Trudeaumania: The Rise to Power of Pierre Elliott Trudeau

by Robert Wright

HarperCollins Publishers

384 pages, $32.99

A double review with

Trudeaumania

by Paul Litt

UBC Press

424 pages, $39.95

Here are two very good books, published simultaneously on the same subject — the ascendancy of Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau. The books’ authors offer very different interpretations of the same phenomena, and there is a large difference in the methodology the authors bring to their common subject. Robert Wright’s book is a well-written, engaging, but almost completely non-theoretical, narrative-type history, while Paul Litt, equally literate in his style and his ability to engage the reader, ventures into theories of technology and postmodernism that call on such philosophical luminaries as Jean-François Lyotard and Jean Baudrillard.

The objects of their gaze are the extraordinary events of 1967–68. In 1967 Canada joyfully lived its centenary year. Canadians, it seemed, were breaking free of prudery and convention. Expo 67 in Montréal represented the country as a place of experiment and creativity. Yet, as Wright emphasizes, Canada was at the very same time in crisis, its politics nearly broken and derelict. Nationalism was increasingly ascendant in Québec. The very year of Expo was also the year René Lévesque formed the movement that would become the Parti Québécois.

When all seemed lost, an unlikely saviour rode to the rescue. A relatively inexperienced intellectual from Montréal, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, came from nowhere and in an astounding rise to power won the Liberal leadership race in April 1968 and the subsequent election two months later. He won these, apparently, with a disarming display of charisma. Trudeaumania had arrived.

Wright’s argument is that Trudeau’s triumphs had nothing to do with charisma, or television, or the new nationalism of the sixties, but everything to do with Trudeau’s ideas. In Wright’s view, Trudeau was not a man of the future but a man of the past who had been honing his intellectual position since 1955 or thereabouts. He advocated an entrenched charter of rights, bilingualism, equality of opportunity, equalization, greater democratic participation, an independent role for Canada in the world, and, in regards to the constitution, opposition to special status for Québec. As Wright puts it very succinctly, Trudeau was not in fact a creature of the screen but of texts: “It was the power of his ideas that impressed the 45.5 per cent of Canadians who voted for him in 1968.”

Wright explicitly itemizes three “myths” about the rise of Trudeau that he wishes to refute, all of them, as it turns out, central to Litt’s position: first, that Trudeau’s triumph depended on the new nationalism of 1967; next, that he was victorious as a result of his ability to dominate and manipulate television; and, finally, that all of his triumphs flowed from a grand strategy of imagery and style.

Litt’s account is less categorical and much more nuanced. He does not doubt that Trudeau had a fine mind and that he had spent a long time refining his political views. He too notices that Trudeau expressed a steady opposition to Québec nationalism. But his view is that Trudeau was something more: He was innately comfortable with the new requirements of television, and he was, willy-nilly, part of the new nationalism that was taking hold of urban, professional, managerial English Canada and that helped to catapult Trudeau to high office. The year 1967 had spawned a new self-confidence among urban, middle-class Canadians; Expo 67 and its experimental, psychedelic, and even sexually subversive atmosphere stood in contrast to the travails of the United States at the time, especially over the war in Vietnam.

Suddenly it became possible to imagine Canada as the peaceable kingdom — and not just as unique, but avant-garde as well. Litt’s claim is that by 1968 journalists and commentators in print, television, and radio — especially in the “cosmopolitan” centres of Toronto, Ottawa, Montréal, and Vancouver — had grown tired of the boring rivalries of John Diefenbaker and Lester Pearson. They wanted a new politics, and they believed they had found it with the advent of Trudeau. Advertising executives, and artists, and fashion designers became cheerleaders for Trudeau, and for the Liberals as well. What they brought about, according to Litt, was a “mod” style of politics, an all-encompassing brand that was exciting and titillating but ultimately politically safe. A new Canada had been born.

Where Litt is impressive is in his theoretical reach. In a crucial distinction, he uses one of Baudrillard’s insights about how modern technology has displaced “reality” and created a world of its own, a world of “ephemeral images on screens,” a simulacrum of reality. In Trudeau’s case, through its fusion with an emergent nationalism, it created something he calls “simunationalism.” Part of the then-new media of television, Litt claims, made politics less about character and more about personality. To be successful the political leader must be a dramatic television performer. In this regard Trudeau was a stunning success. He delighted in playing to the cameras.

Litt’s advantage in this battle of competing interpretations is that his perspective is able to accommodate many factors, rather than emphasizing just one as Wright does. The latter’s point of view needs to be informed by that other integral feature of Trudeau’s character: his pragmatism. Trudeau was a fine intellect, but he was also a man of action who shaped his ideas as a prelude to actual engagement. As a pragmatist he was prepared to seize the moment and its context. Trudeau’s brilliance was that he could master the lecture hall and the TV screen. Appreciating such multiple talents fits more easily into Litt’s account of him than Wright’s.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement