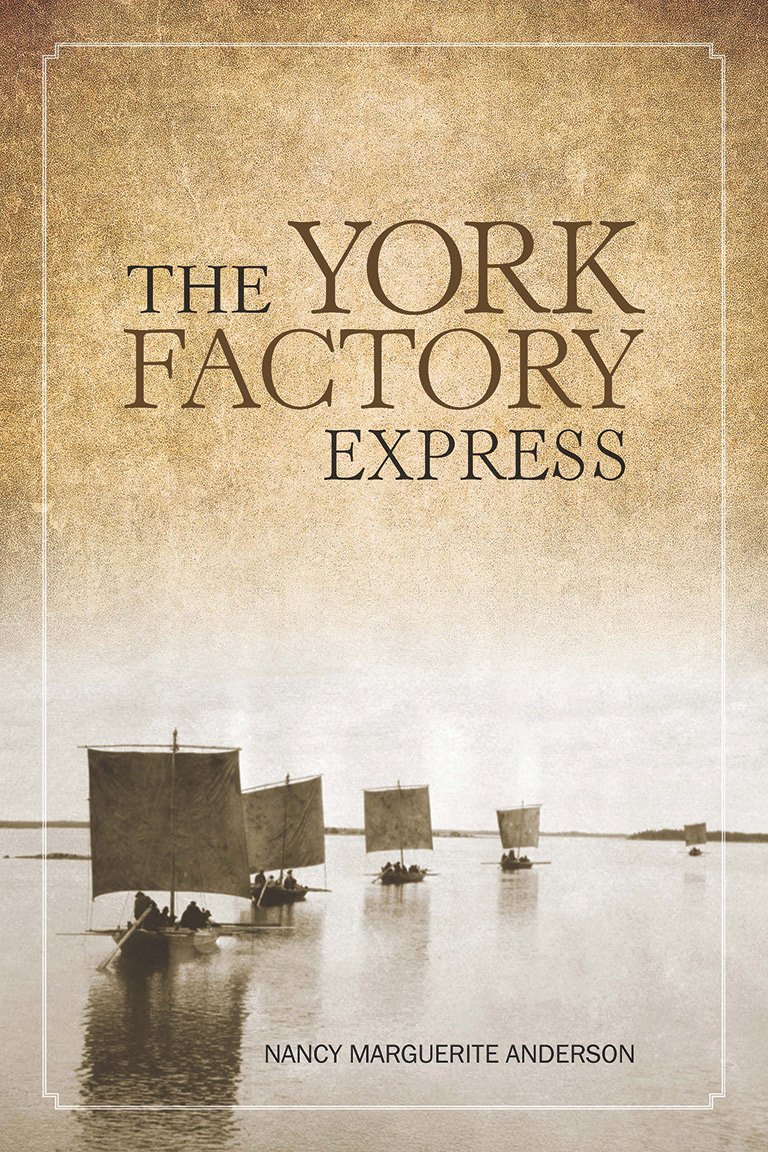

The York Factory Express

The York Factory Express: Fort Vancouver to Hudson Bay, 1826–1849

by Nancy Marguerite Anderson

Ronsdale Press

305 pages, $24.95

This fascinating book follows the journey of mid-nineteenth-century travellers along the route of the famed York Factory Express. The express was a special freight and communication service of the Hudson’s Bay Company that transported the company’s voluminous correspondence and records between its farthest-flung outposts in the Columbia District — the vast territory west of the Rocky Mountains that includes today’s British Columbia and the U.S. states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, along with parts of Montana — and the company’s North American headquarters at York Factory on the western shore of Hudson Bay.

The express involved about thirty men using canoes and York boats who departed Fort Vancouver, approximately 150 kilometres inland from the Pacific Ocean along the Columbia River, in early March and made an epic 4,200-kilometre return journey to York Factory, in what’s now northern Manitoba, and back in a single season. A remarkable feat of logistics, danger, and perseverance, it operated between 1826 and 1855, when it was supplanted by a sea-based route that included the new rail service across the isthmus of Panama.

The men who were selected to power the express earned boasting rights: They travelled fast while logging long days through dangerous conditions and enduring privations that were exceptional even for their time. The majority of the voyageurs who propelled the express were young Canadiens, Métis, or Iroquois who prided themselves on their abilities. Only the most skilled and vigorous voyageurs were allowed to undertake the journey.

Author Nancy Marguerite Anderson is the great-granddaughter of James Birnie, who travelled with the first York Factory Express. She sets the discussion and overview around six main characters — express leaders who wrote journals of their daily trials and adventures as they travelled east in the spring and back west in the fall. This is a good narrative choice, showing the journey as it would have been undertaken according to the seasons and highlighting the human aspect of the enterprise rather than a list of its technical accomplishments.

The six main stories are enlivened with interesting excerpts from the writings of others who travelled the route, bringing to life the enterprise and its legions of often-anonymous workers while providing a window into the experiences of the hundreds of young men who made the monumental traverse. Anderson is particularly interested in the daily details and stories that occurred along the route that was riddled with rapids, portages, snowy mountain passes, swollen rivers, prairies, and boreal forests. It was a truly epic undertaking to travel so far with such basic technology.

In addition to transporting documents that were vital to the management of the company’s widespread operations, the express carried paying passengers, employees travelling to meetings at York Factory, Norway House, or the settlement at Red River, and employees on furlough — a sort of sabbatical year given to senior employees. For outsiders desiring entry to the company’s domain — whether priests or missionaries, travelling gentlemen or botanists like David Douglas, or, as the century progressed, settlers who wanted to be near to company outposts for access to supplies — the express was the only regular transportation to the Far West.

Anderson peppers her story with thoughtful commentary that places the men’s experiences in the context of the times and invites thinking about the past in general. “They learned the names of old places we no longer remember,” she observes, and “they camped near the ruins of old posts and heard stories of battles and murders that happened half a century earlier.”

The narrative also includes littleknown details of life in that era. For example, regarding the maintenance of boats, Anderson writes that “their seams, which opened in the heat of the sun or under the strain of rapids, were stuffed with batten and pitched and gummed frequently to keep them afloat. … They melted the pitch into the seams of the boat by drawing two pieces of burning firewood along each seam, ‘blowing at the same time between the sticks, this melts the gum, and a small spatula is used to smooth it off.’ To a stranger, it appeared as if the voyageurs were ‘burning their boats behind them.’”

In her thoughtful epilogue Anderson notes that many of the voyageurs remained west of the Great Divide after their contracts with the company expired. As they settled and integrated with new waves of English- speaking immigrants, their distinctive culture and French language gradually faded. She writes that, when faced with persistent prejudice, “the fur trade descendants put their Indigenous past behind them and did not mention it … to be absorbed into whichever community we felt most comfortable in.”

The York Factory Express provides a fascinating window into the lives of a distinct group of men who led daring, adventurous lives and who were the driving force behind one of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s least known yet most epic transportation ventures.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement