The Ward Uncovered

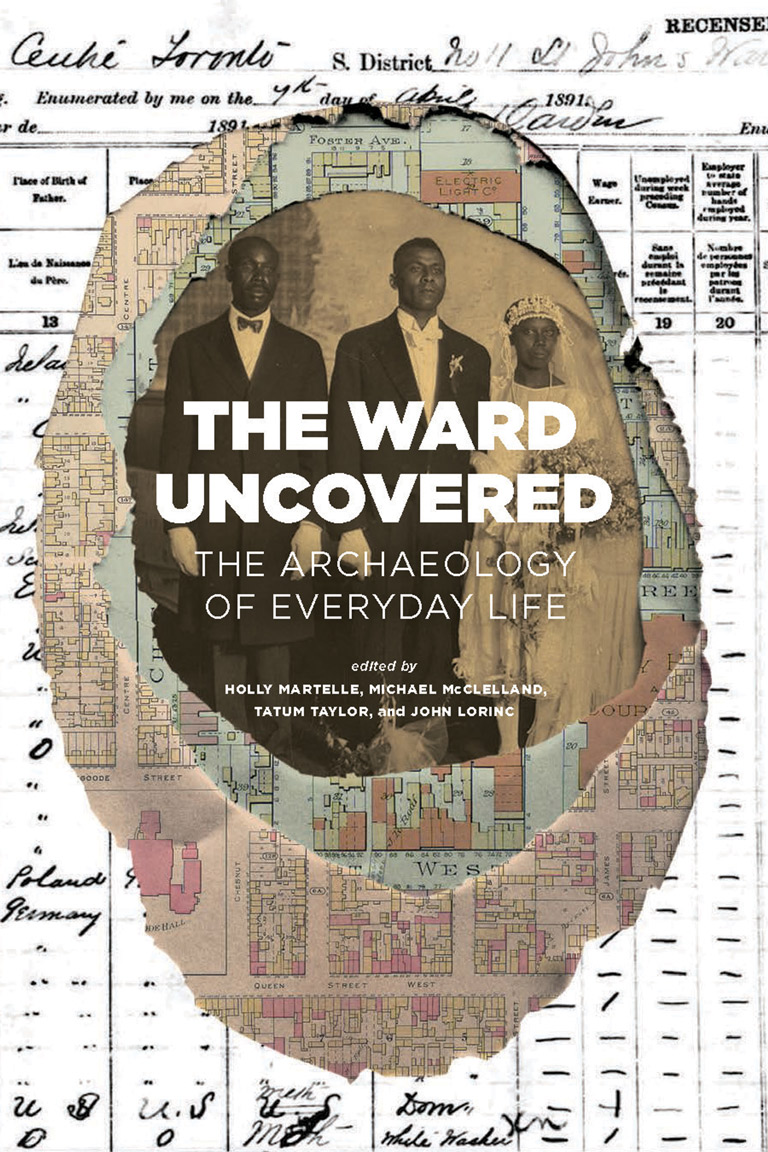

The Ward Uncovered: The Archaeology of Everyday Life

edited by Holly Martelle, Michael McClelland, Tatum Taylor, and John Lorinc

Coach House Books, 304 pages, $27.95

While tidying guru Marie Kondo’s method of purging items that don’t “spark joy” is sweeping the nation, archaeologists are bucking the trend. Indeed, our mess is their key to unlocking the past and its secrets.

In 2015, a team of archaeologists began an urban dig in the heart of Toronto’s downtown, uncovering the evidence of the Ward — a dense and diverse immigrant neighbourhood that thrived from the 1840s to 1950s.

The Ward Uncovered uses the ordinary objects its residents left behind — a soda bottle, a hat mould, an inkwell — to reconstruct the lives of these newcomers and to allow their voices to be heard.

From the first pages, the book’s editors declare that “the object is the subject.” This is more provocative than it might seem, when taken within the context of historic record itself. For generations, men with power shaped history, considering it their story to tell.

The counterculture of the 1960s broke down this monopoly, with new perspectives breaking through, including an approach called “history from below.” Mostly for the first time, the lived experiences of the working class, immigrants, the poor — in other words, men and women like those who occupied the Ward — were the subject of historic narratives.

However, The Ward Uncovered takes this one crucial step further, to the things that compose everyday life. We’re talking ordinary items — garbage, even.

And yet, those objects tell us a story, if we pay attention. No one really thinks about the history of a ubiquitous urban feature such as a parking lot; it might be hard to imagine that such a patch of asphalt once marked a vibrant “arrival city” for immigrants in Canada’s leading metropolis.

The book is composed of short essays by different contributors, carefully pieced together in thematic sections that are designed to peel back each layer of the lives of the Ward’s residents. It thereby mimics an archaeological dig in a highly effective way.

The artifact is always the starting point. Fish bones found in an excavation of a privy suggest that Irish-Catholic immigrants maintained “Old World traditions.” In other privies, gilded ceramic plates and coconut husks defy expectations as signs of luxury amid poverty. The foundations of a Russian synagogue and of a Black church reveal themselves to be more than centres of community and religious life — they were also safe havens for minorities escaping oppression and enslavement.

Readers get to encounter the residents, seeing their actual possessions through beautiful, full-colour photographs or hearing them in their own words through letters and interviews. As Holly Martelle puts it, archaeology is both “science and storytelling.” The Ward Uncovered gives readers both, but it’s the stories that shine through.

There is much to unpack in The Ward Uncovered, but the effect is intentional. Each essay builds intimacy between the reader and the subject. We begin to feel that we know each other as we learn what the Ward’s residents ate, where they worked, how they socialized, and how they fought for equality. We learn this in the smallest, most ordinary of ways and in big ways, too.

When I put down this book, one question lingered: How will archaeologists and historians truly know the stories of our present day-to-day experiences in another two hundred years? Key parts of our lives wind up in landfills. And is social media our dumping ground, our virtual privy?

The Ward Uncovered allows us to know people who have often been left out of history, and it not only leads us to our shared past but points to the future: How will we be known? What do we leave behind?

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement