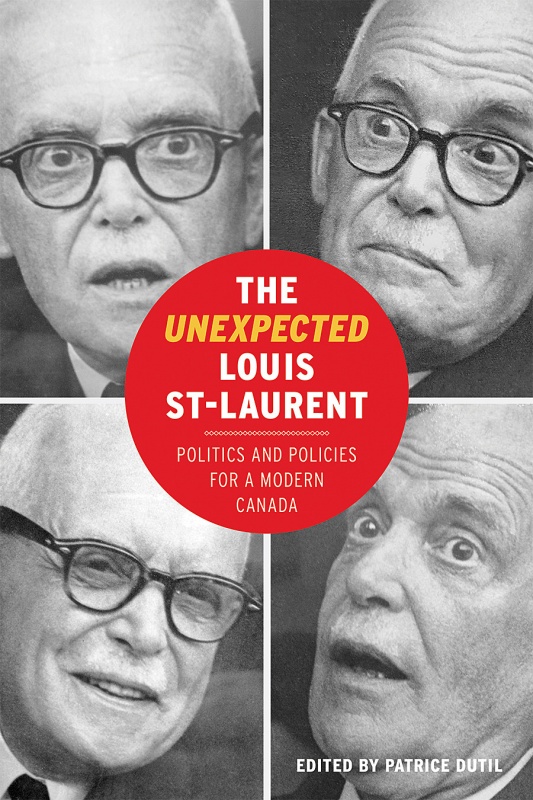

The Unexpected Louis St-Laurent

The Unexpected Louis St-Laurent: Politics and Policies for a Modern Canada

edited by Patrice Dutil

UBC Press

540 pages, $49.95

Louis St. Laurent, Canada’s twelfth prime minister, is largely forgotten today. Even as he guided Canada into the prosperous second half of the twentieth century, as prime minister from 1948 to 1957, he attracted few historians to write his story.

Part of the problem was his failure to leave a diary, or many personal letters — although for decades historians have called for a new study of his victories and defeats, his successes and failures. Finally, the talented political scientist Patrice Dutil, author of many books of political history and public policy, has brought together two dozen experts to study St. Laurent and his legacy in The Unexpected Louis St-Laurent.

In twenty-two articles, leading scholars such as J.R. Miller, David MacKenzie, and Stephen Azzi, along with St. Laurent’s granddaughter Jean Thérèse Riley and former Quebec Premier Jean Charest, shed new light on the elusive figure who has often been portrayed as a benign grandfather type — or Uncle Louis, as he was known. St. Laurent was these things at times, but one does not scramble to the top of the slippery political ladder without being willing to crush opponents and colleagues. He did that, and he governed with a firm hand, velvet over iron. He was not the mere chairman of the cabinet, as was often said of him; rather, he guided his ministers, absorbing advice, listening to different opinions, and reaching conclusions as he saw fit.

The book’s contributors elucidate many areas of study, including how St. Laurent came to power and kept it until his defeat in 1957 by John Diefenbaker; how his pragmatic realism was tinged with idealism; how he positioned Canada to engage in world affairs; and how he addressed matters of health, social policy, communism, crime, and finance. This is a book about St. Laurent as a leader facing insecurity abroad and prosperity at home. His time was also an age of conformity, sexism, racism, and bigotry, and several authors address these issues — especially through the lens of policy and actions that affected Indigenous people.

St. Laurent left a legacy of infrastructure projects like the St. Lawrence Seaway, the RRSP system, an influx of immigrants, and, his proudest accomplishment, guiding Newfoundland into Canadian Confederation in 1949. Several chapters explore St. Laurent as a Canadian nationalist, repositioning Canada to embrace its own cultural destiny, with more funding for the arts and for the creation of new bodies. He also led Canada forward, embracing a stronger international focus because, as he stated in some of his most famous words, in response to the vexing Suez Canal Crisis of 1956, “the era when the supermen of Europe could govern the whole world is coming pretty close to an end.”

The prime minister’s agenda was furthered by a strong cabinet and some of the best civil servants in Canadian history, and both groups are explored in most of the book’s articles. In particular, his dynamic relationship with Lester B. Pearson is presented in detail. St. Laurent later remarked of his protege, who was prime minister of Canada from 1963 to 1968, “I believe that our partnership during [the 1950s] enabled us to do together much that neither of us could have done separately to serve Canada.”

While thorough and wide-ranging in covering multiple subjects and themes, The Unexpected Louis St-Laurent is not definitive. I would like to have seen a chapter on St. Laurent’s role as a wartime prime minister during the Korean War as well as more about his policies to address the inequality faced by women. Nonetheless, what is clear, both in the parts and in the whole, is that the best leaders, like St. Laurent, make being prime minister look easy. It never is, and Dutil’s important book shows us how and why that was the case during the mid-twentieth century.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement