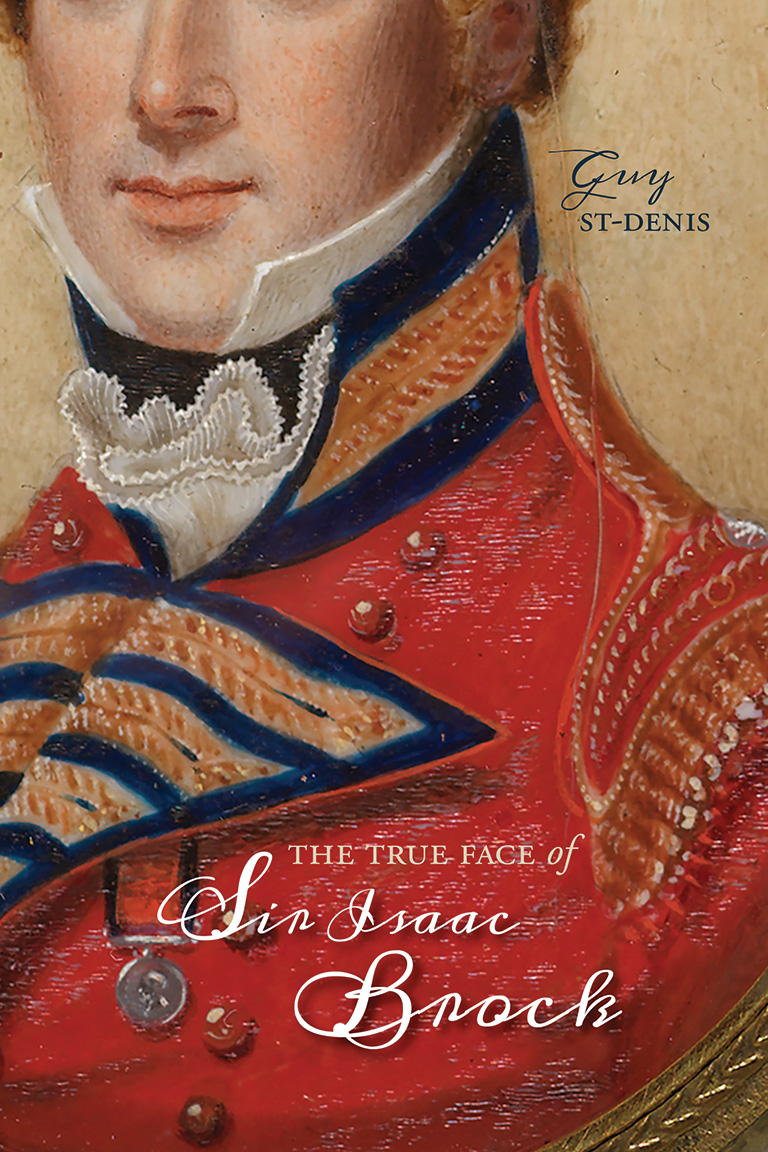

The True Face of Sir Isaac Brock

The True Face of Sir Isaac Brock

by Guy St-Denis

University of Calgary Press,

330 pages, $34.99

Canadians with even a loose grasp of their national story likely have a notion of what important historical figures looked like, or what they’ve been imagined to look like. The advent of photography roughly coincides with the road to Confederation; hence there is no shortage of real-life pictures of Sir John A. Macdonald and the Fathers of Confederation, and there are also quite a few reliable images of the mothers, wives, and daughters of Confederation.

Before the development of photography, though, historical portraiture was an infinitely more dubious and unreliable domain. A notable example is Samuel de Champlain, the undisputed colonial founder of Canada. The goateed face we see on innumerable statues and textbook illustrations is, as intrepid historians have revealed, a much-copied version of the portrait of an obscure French bureaucrat.

London, Ontario-based historian Guy St-Denis encountered the pitfalls of portraiture as he embarked upon what was originally supposed to be a new biography of Sir Isaac Brock, one of the most lauded heroes of the War of 1812. In rounding up illustrations for his proposed book, St-Denis soon found himself on a quest to determine, as the book’s title declares, Brock’s “true face.” That quest eventually produced enough material for its own book.

“After consulting diverse and farflung manuscript collections for the better part of a decade,” St-Denis concluded (spoiler alert) that there really is only one verified true portrait of Brock as an adult. (There is also an authentic portrait of him as a sixteen-year-old ensign). Brock sat for this one portrait, a twenty-by-twenty-three-centimetre profile pose, “sometime between May of 1809 and July of 1810” while stationed in Quebec City. The portraitist was Gerrit Schipper, described as a “Dutch itinerant artist.”

St-Denis has some experience unravelling historical mysteries. His 2010 book, Tecumseh’s Bones, explored what might have happened to the remains of the Indigenous war leader and Brock ally Tecumseh. It also provided the author with a considerable amount of research on Brock himself.

Perhaps St-Denis’s single most important contribution to the Brock record is the definitive debunking of one of the most commonly misidentified portraits of the fabled defender of British North America. The fullfaced miniature portrait of a handsome, blond, curly-haired young man in a British officer’s uniform, reputedly handed down by relatives of the fallen commander, was revealed to be the visage of another officer, Lieutenant George Dunn.

St-Denis credits German immigrant Ludwig Kosche, a historian at the Canadian War Museum, with doing the major detective work, including trips to Guernsey, Brock’s birthplace, where the hero’s family abounds, his memory is revered, and the original of his one authentic portrait hangs in the island’s museum. (The portrait made a return visit to Canada in 2012 for the bicentennial of the War of 1812; it was on display at the RiverBrink Art Museum in Queenston, Ontario.)

Kosche, incidentally, got the Brock bug through his mission at the war museum to authenticate one of its prized possessions, the scarlet coat Brock wore when he was cut down by an American sniper’s bullet at the battle of Queenston Heights, on October 13, 1812.

The True Face of Sir Isaac Brock is a bit of a challenge to read in some stretches because of the proliferation of versions of portraits and the multitude of characters trying to prove or to deny their veracity. Still, the occasional density of the text is evidence of the depth of research St-Denis has undertaken. To that end, he has provided thirty-four pages of plates, most in colour, of the works discussed in the text as well as summaries of their provenances.

The reader does not learn a lot more about the life and times of Sir Isaac Brock, the man and war hero; but St-Denis’s exploration of the trail of Brock’s portraiture reveals a vast amount of fascinating information about his family, his descendants, and his admirers, as well as their efforts to uncover, to authenticate, and to preserve his likeness.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement