The Roosting Box

The Roosting Box: Rebuilding the Body After the First World War

by Kristen den Hartog

Goose Lane

280 pages, $24.95

In this evocative history, Kristen den Hartog explores the legacy of Canada’s wounded Great War soldiers and Toronto’s Christie Street Hospital. It was a centre for the care of veterans, with thousands passing through it over the years. Some did not leave alive, too badly maimed in body or mind to ever again function in Canadian society.

The book’s title, The Roosting Box, comes from the name for a communal space that offers shelter for the vulnerable. Readers encounter dozens of patients, learning of their history of serving and fighting at the front as well as their terrible life-changing lacerations and injuries. “Man’s ability to repair,” wrote one surgeon, “must always lag a little behind its ability to destroy.” The incredible medical advances that were made during the war saved many from death, even if their bodies had been shattered and torn apart.

Based on her research into medical care, hospital culture, rehabilitation, and other life-saving developments, den Hartog writes with a novelist’s eye and tremendous sympathy for her subjects. She draws upon photographs, archives, and newspaper accounts as she reveals the veterans’ experiences and their slow recoveries.

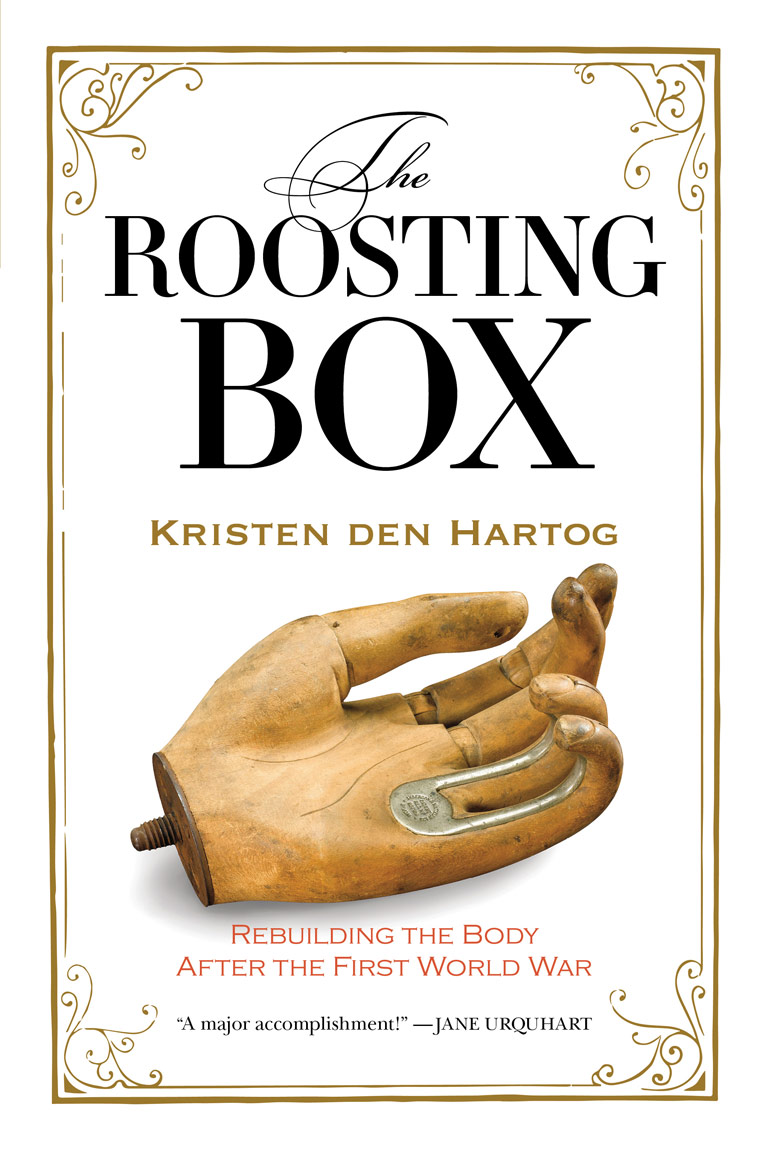

Not all patients could be relieved of their afflictions. Men with burned-out and ravaged lungs from chlorine, phosgene, and mustard gas wheezed and hacked from minimal exercise, desperate for any treatment to alleviate the pain. Rarely could they be helped. Victims of tuberculosis — a great killer of Canadians at the time — were given open-air treatment at the hospital, with the hope that sunlight would assist them in recovering their endurance. Those who had lost hands, arms, and legs needed to be fitted with prosthetics, and both the limb-making process and the steps involved in retraining the maimed make for fascinating if difficult reading.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The nurses at the hospital, many of them war veterans, gave much of themselves in their efforts to ease pain and to transition the injured out of the wards. Treatments often involved the use of X-ray machines, skin grafts, and facial reconstruction. Occupational therapists assisted those with dire wounds, although little could be done for soldiers suffering from the phantom pain they experienced from lost limbs.

Lorne Mulloy, a famed South African War veteran who was blinded in that conflict, lectured the wounded veterans about this even more terrible war and urged self-reliance: “Happiness is obtainable only through work — is possible only for a man who successfully finds his way back to productive activity.” The message of overcoming injuries echoed forth across society, and den Hartog might have made more of a poster she describes — its caption reads: “Once a soldier, always a man” — and what it reveals about fears of diminished masculinity for the physically disabled.

While the wounds and their treatments make for illuminating reading, The Roosting Box is strongest when drawing out the stories of the many individual veterans as they struggled to embrace their new lives. Hugh Russell was nineteen when he enlisted in London, Ontario. He had a love of horses and agonized over seeing so many of them killed during the conflict, writing that the screaming animals were “worse than seeing men cut up. The men have an idea what it is all about but the horses have to take it as it comes and say nothing.”

Russell was later buried by an exploding shell and suffered shell shock. His recovery was slow, and, like many of the soldiers with mental wounds, he could never leave behind the horror of the Western Front. Russell was treated at the Christie Street Hospital, where he and other patients screamed at night and twitched during the day.

Service records note that some veterans suffering from what we would now call post-traumatic stress disorder trembled with a “hysterical gait,” while others heard imaginary noises and ducked for cover. The soldiers’ enduring mental trauma is a metaphor for the darkness cast across Canada by the Great War, including long after the guns fell silent.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!