The Right to Read

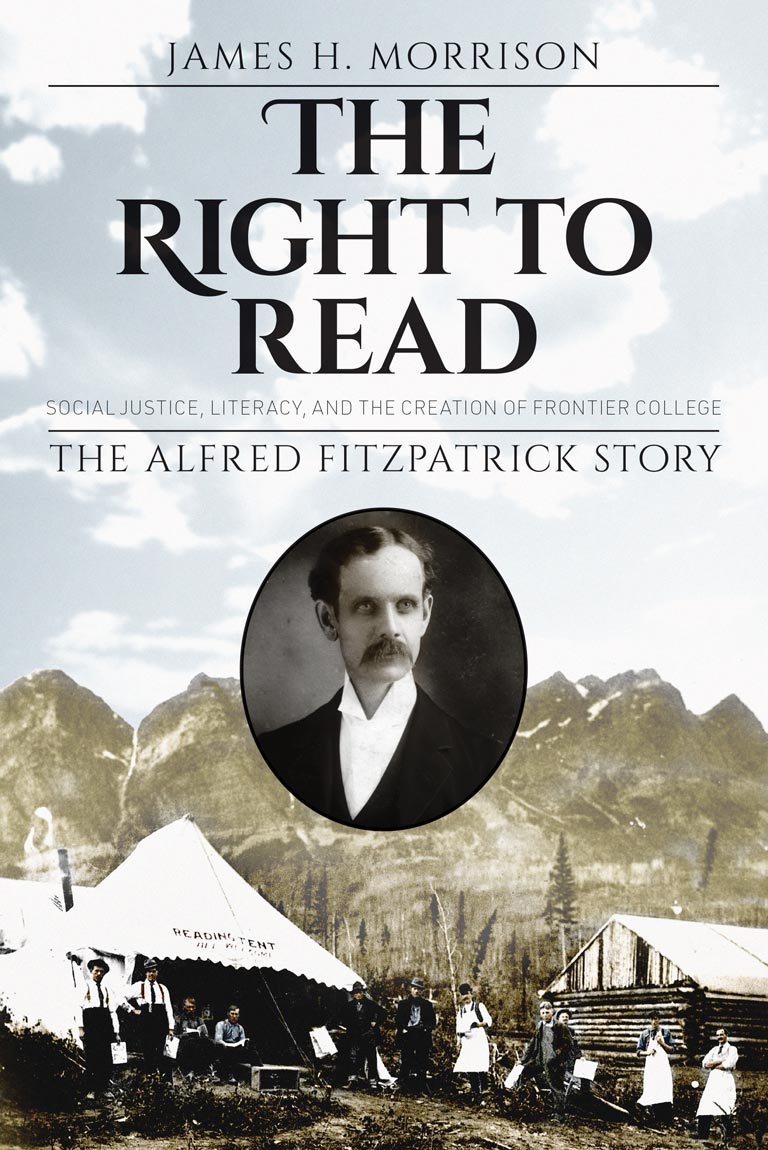

The Right to Read: Social Justice, Literacy, and the Creation of Frontier College: The Alfred Fitzpatrick Story

by James H. Morrison

Nimbus Publishing

288 pages, $24.95

It may not be immediately evident from the title, but this book feels current. The social-justice issues raised a century ago by visionary reformer Alfred Fitzpatrick have evolved, yet they’re still alive today. The fundraising challenges, personality conflicts, and power struggles of the past would be familiar to contemporary social activists.

Fitzpatrick held progressive views that were well ahead of his time. He sacrificed much to devote his life to a singular cause: bringing education to adult workers in remote locations. In 1899, he established what became known as Frontier College.

Fitzpatrick was born in 1862 on a farm in Pictou County, Nova Scotia, the eleventh of twelve children. Like the other Scots Presbyterian children of the region, he was raised on a strict diet of “oatmeal porridge and catechism.” He received scholarships to train for the ministry at Queen’s University, where he learned about the social gospel, a new movement that applied Christian ethics to the social problems brought on by industrialization.

Fitzpatrick was sent to Revelstoke, B.C., during a summer break for mission work in remote forestry camps. This changed the course of his life. It was there that the nattily dressed Fitzpatrick encountered illiterate labourers struggling under harsh conditions. The men, many of them new immigrants, worked dawn to dusk six days a week for low pay, living together in crowded, filthy bunkhouses. Death or dismemberment from the dangerous work of felling trees and driving logs was not uncommon.

The shocked young student minister realized that two of his brothers, who had gone to California to make a living felling giant redwoods, had been in similar circumstances. One of them, Leander — who was also his best friend — had died driving logs on a river. Fitzpatrick felt this loss keenly, and it likely fuelled his passion for reform.

Fitzpatrick never took to the settled life of the manse. He changed jobs frequently and eventually stopped ministering altogether to establish the Canadian Reading Camp Movement. University-student volunteers travelled to isolated work camps, bringing books and setting up reading tents while also toiling alongside the labourers.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, who thought illiterate adults were too old to learn, Fitzpatrick believed that everyone was teachable. He also believed that education would instill values of citizenship and morality while providing workers with opportunities for a better quality of life.

Volunteer worker-instructors included people like Norman Bethune, who would go on to pioneer mobile blood-transfusion methods during the First World War, as well as Benjamin Spock, who later wrote the influential The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care. Women like Dr. Margaret Strang, who worked on horseback in the Peace River district of Alberta, northwest of Edmonton, also joined the effort.

As the book frequently points out, Fitzpatrick had great confidence in women’s abilities and often relied on the judgment of his female employees. He leaned heavily on the steady wisdom of college registrar Jessie Lucas, who would spend forty-three years at Frontier College, outliving both Fitzpatrick and his successor, Edmund Bradwin.

There are many facets to this story, and author James H. Morrison — himself a labourer and teacher with Frontier College in 1964–65 — illuminates them very well.

For instance, the working relationship between Fitzpatrick and Bradwin was complementary but tense. While Fitzpatrick was slim, restless, and overflowing with big ideas and ambitions, Bradwin was tall, steady, and pragmatic. They respected each other, but, in the end, they clashed mightily over the college’s future.

The underlying story here is the struggle to obtain steady funding. Potential funders commonly saw educating the adult working class as a lost cause. Fitzpatrick spent most of his time tapping his contacts in government, universities, industry, and elsewhere for financial support. In doing so, he stepped on some toes.

For instance, his success in obtaining a federal charter to grant degrees alienated provincial governments, who considered universities their jurisdiction. Thus, the Ontario government cut off Frontier College’s meagre grant for several years in the 1920s — something that almost led to the school’s collapse.

Fitzpatrick spent much of his salary covering college expenses and lived frugally, usually in boarding houses. He never married, and he died with few possessions.

Frontier College still exists today. Now called United For Literacy, the charitable institution offers free tutoring for all ages — and, like its visionary founder, the organization maintains that literacy is key to “advancing social equity and prosperity.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement