The Lost Wilderness

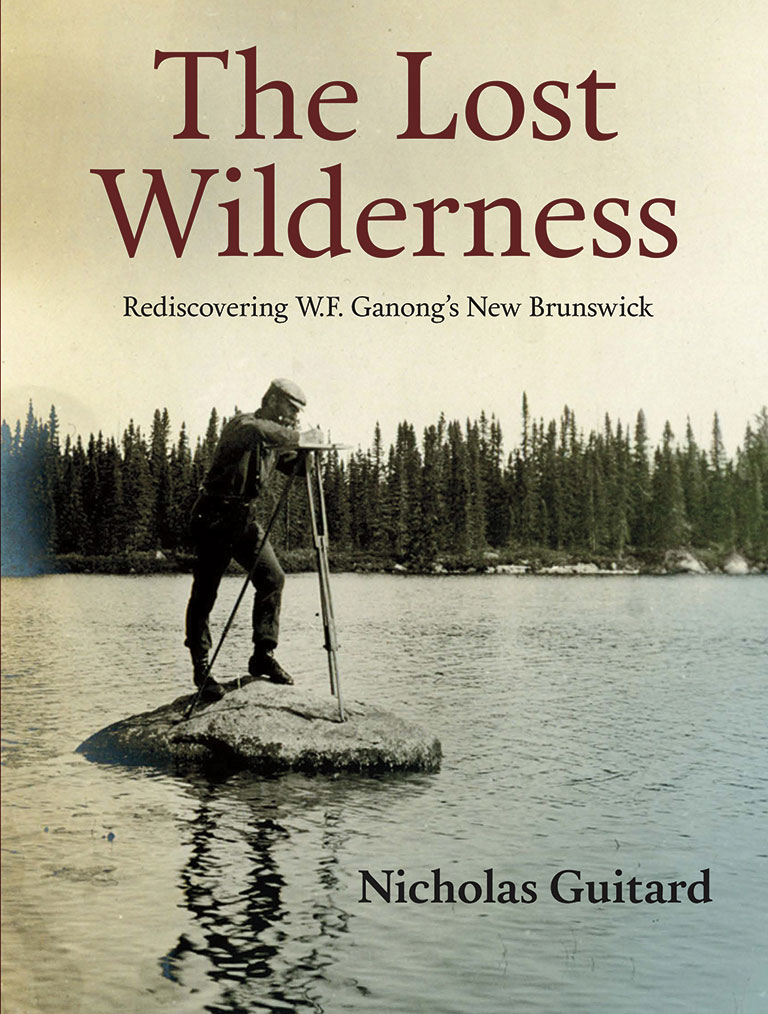

The Lost Wilderness: Rediscovering W.F. Ganong’s New Brunswick

by Nicholas Guitard

Goose Lane Editions

232 pages, $24.95

A double review with

New Brunswick Was His Country: The Life of William Francis Ganong

by Ronald Rees

Nimbus Publishing

260 pages, $24.95

Like many people who have been officially designated “Persons of National Historic Significance,” William Francis Ganong is not exactly a celebrity. If Canadians outside of New Brunswick recognize his name at all, it’s likely because of its connection to chocolate. Ganong Bros. of St. Stephen, New Brunswick, is Canada’s oldest candy company.

But W.F. Ganong never entered the family business. He became a brilliant scholar, cartographer, scientist, and geographer and is recognized for those accomplishments. Given his relative obscurity — he died in 1941 — it’s intriguing that two authors recently chose to reintroduce him to the public.

Nicholas Guitard, an acclaimed photographer and naturalist, turned his fascination with Ganong into The Lost Wilderness, a visually appealing book with maps or photographs on almost every page. Most interestingly, it juxtaposes photos of the landscape taken more than a hundred years ago with contemporary pictures of the same scenes. Sometimes the alteration is dramatic; other times there is little evidence of change.

Guitard’s focus is on a handful of the many field trips Ganong undertook during his summer breaks from teaching botany at Smith College in Massachusetts. These forays into New Brunswick’s wilderness yielded a wealth of information about the province’s natural history. Included are many quotations from the notebooks of Ganong and his travelling companions.

Ganong comes across as very focused and driven; his wilderness partners had a hard time keeping up with him. Mostly, this is an account of where Ganong went and what he did, and not so much of who he was as a person.

New Brunswick Was His Country, by Ronald Rees, a former professor of historical geography, is a more traditional biography. There are fewer illustrations but more details about Ganong’s life. For instance, as a child he was so “obsessively orderly” that he recorded agreements with his siblings and tracked responsibilities for household chores. As a young man, Ganong was philosophical and poetic: “What man, if he love beauty of form, could not be moved by the arrowy flight of the cuttlefish….” Later in life, less inclined to flights of fancy, he took pride in his intellectual rigour.

Ganong was good-natured but frank. After he insisted to the Anglican priest who was to conduct his marriage to Muriel Carmen (poet Bliss Carmen’s sister) that he was an atheist and a believer in Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, no Anglican church in the Dominion would marry them. They had to proclaim their vows at a more liberalminded church across the American border.

A man who mastered many subjects — botany, geology, zoology, Indigenous languages, map-making, history — Ganong is considered a great scholar. But, while he received many honours, he was never a star. As Rees explains, Ganong had no interest in promoting himself. He wrote for nonprofessional audiences; he took care to balance his research with good teaching; he attended few conferences and belonged to few professional societies. “He was as unlike the modern networking, career-oriented academic as it is possible to be.” For that alone, Ganong deserves our attention today.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement