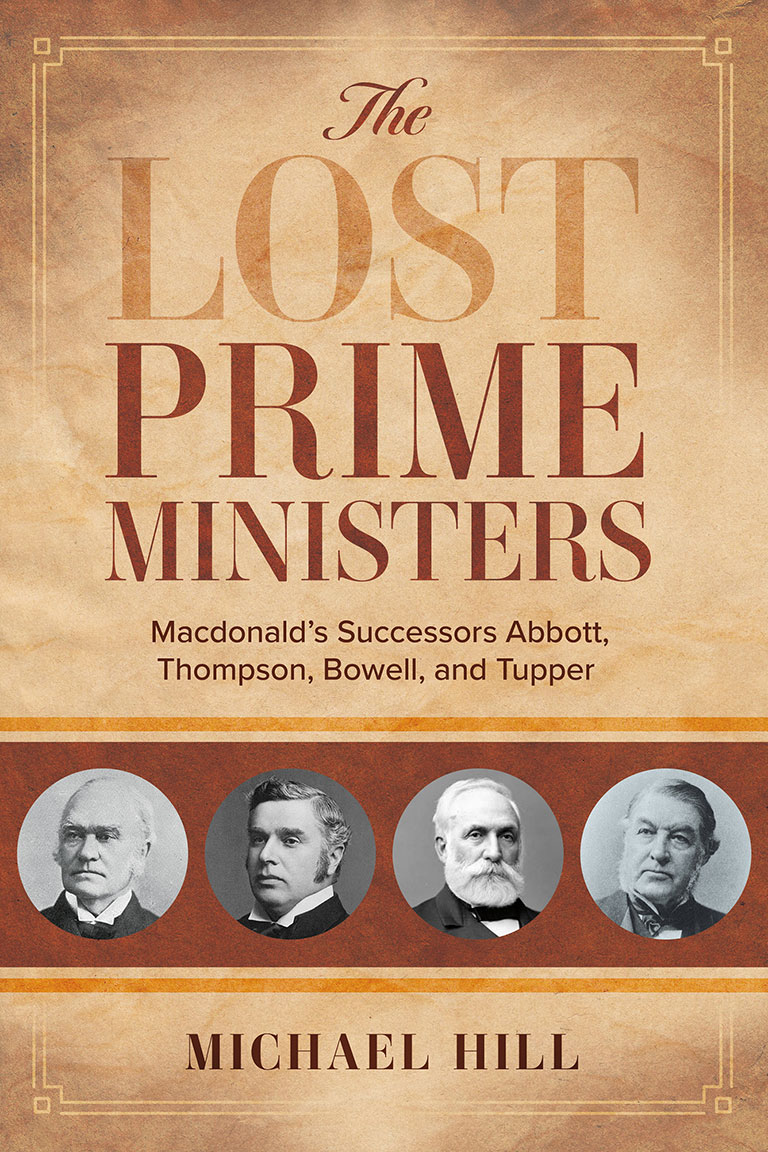

The Lost Prime Ministers

The Lost Prime Ministers: Macdonald’s Successors Abbott, Thompson, Bowell, and Tupper

by Michael Hill

Dundurn Press

279 pages, $24.99

Test your knowledge of Canada’s political history with this question: Who were the four men who succeeded Sir John A. Macdonald and served as prime minister between 1891 and 1896? If you said John Abbott, John Thompson, Mackenzie Bowell, and Charles Tupper, take a seat at the head of the class.

This quartet of Conservatives has been eclipsed by the giants who came before and after them, Macdonald and Wilfrid Laurier. Ontario writer Michael Hill, a former history teacher and Toronto Star columnist, gives this forgotten four the star treatment in The Lost Prime Ministers, an enlightening, entertaining, and easy-to-read account.

“I hate politics … I hate notoriety,” Abbott noted shortly before he was handed the highest office in the land. When Macdonald died at age seventysix in June 1891, three months after winning his sixth general election, there was no succession plan and no obvious successor to lead the fractious party. Abbott was dragooned into serving, despite the fact that he was a senator, and even though Macdonald himself had believed that the seventyyear- old former mayor of Montreal possessed “none of the qualities needed in a prime minister.”

A reluctant caretaker, he lasted seventeen months until ill health forced him into retirement and John Thompson, a former Nova Scotia premier and judge, stepped up to the plate. The smartest man in the cabinet room, he was the justice minister who had introduced the Criminal Code during Abbott’s tenure, standardizing the law across the country, and who had been Macdonald’s obvious successor. But his conversion to Catholicism did not sit well with Ontario’s Protestant Tories, who balked at his taking power until there was no one else up to the task.

Canada’s first Catholic prime minister, Thompson was “the right choice for the party” and “the right person to lead the country,” Hill writes. He was only forty-seven when he took office and should have led the Conservatives into the next election. Tragically, he had little time to make his mark; in December 1894, two years into the job, he died of a heart attack at Windsor Castle during an official visit to England. Canada lost “a thoroughly decent, moral, and dedicated man,” laments Hill, who calls him the “great might-have-been” prime minister.

It was all downhill from there. Mackenzie Bowell was an Ontario senator and former newspaperman who was next in line simply because he had been in cabinet longer than anyone else. He was in his early seventies — his fellow ministers called him “Grandpa Bowell” — and was quick-tempered, indecisive, and ill-suited to lead. Unable to deal with the divisive dispute over Frenchlanguage education in Manitoba, and with his cabinet in revolt, he resigned after fifteen months in office.

His replacement, the fifth prime minister in five years, was Sir Charles Tupper, a Macdonald loyalist called home from his sinecure as High Commissioner in London to rally the troops. At seventy-four the doctor turned politician was in no position to put a fresh face on a tired government that had been in power far too long; he was truly yesterday’s man, a Father of Confederation who had forced his recalcitrant fellow Nova Scotians to become Canadians three decades earlier. It was time for a change, and Laurier and his Liberals cruised to victory in the 1896 election. Tupper still holds the record for the shortest tenure as prime minister — a mere sixty-nine days.

Hill digs into his subjects’ professional and political careers before their stints as prime minister and explores what they were able to accomplish in office as well as the shortcomings, missteps, scandals, and internal party bickering that undermined their effectiveness. He takes pains to include the ways their spouses contributed to their careers. There’s even some contemporary resonance, as today’s still-fractious Conservative Party struggles to find someone to lead it.

The fact that Abbott, Thompson, Bowell, and Tupper have been relegated to the footnotes of history is proof of the long shadow our first prime minister cast over his colleagues. Thanks to Hill’s book, readers can rediscover Sir John A.’s once-lost successors.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement