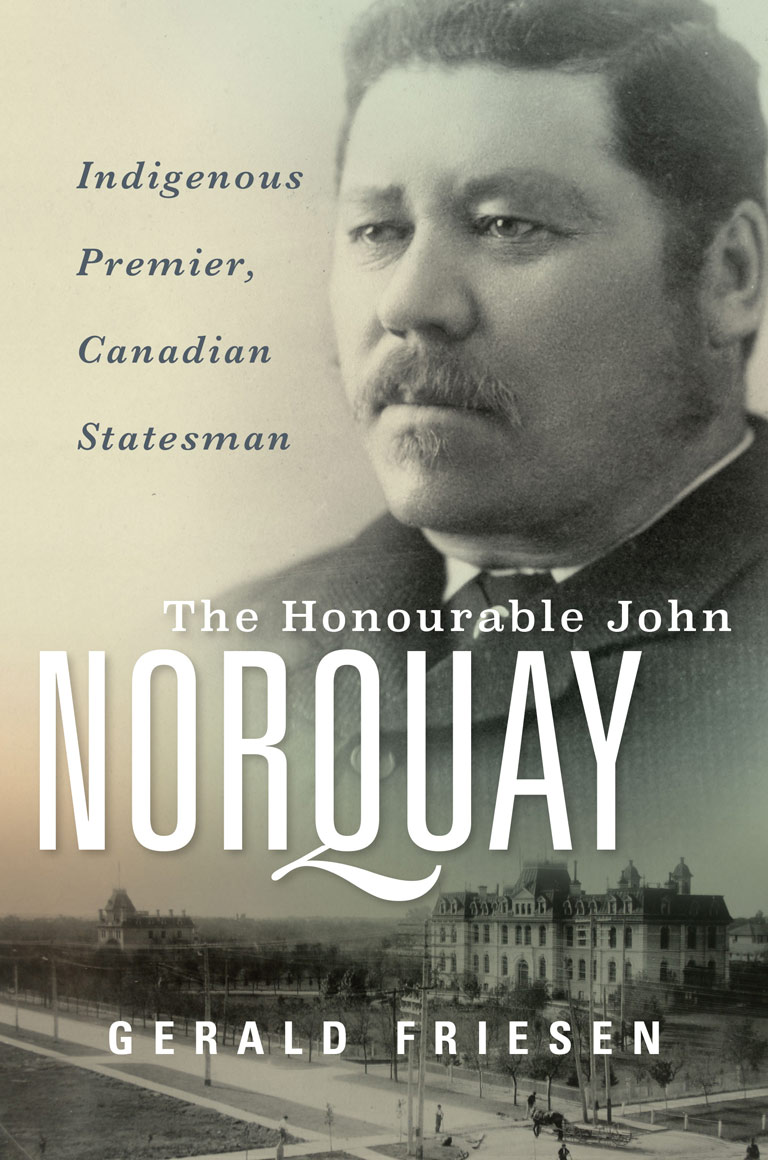

The Honourable John Norquay

The Honourable John Norquay: Indigenous Premier, Canadian Statesman

by Gerald Friesen

University of Manitoba Press

667 pages, $39.95

It is truly fortuitous that Gerald Friesen’s newest book has arrived this spring. Just last fall, several media outlets in Canada were claiming Manitoba’s new premier, Wab Kinew, to be the nation’s first Indigenous provincial leader. Then, in February of this year, the Manitoba government officially recognized Métis leader Louis Riel as the province’s honorary first premier.

Yet John Norquay, a contemporary of Riel, was the same province’s premier from 1878 to 1887. Friesen’s The Honourable John Norquay: Indigenous Premier, Canadian Statesman offers a look into the personal and political life of a man whose contributions have gone largely unheeded.

Born in the Red River Settlement, Norquay was orphaned by the age of eight. His great-grandmother was an Indigenous woman, and his paternal family line consisted of labourers for the Hudson’s Bay Company. He was among the Bungee/anglophone peoples of the community who “played a special role as bridge builders and mediators in the settlement.” Bungee is a variant of English that was spoken by people of mixed Indigenous-British ancestry. Friesen refrains from identifying Norquay as Métis — a term he uses foremost regarding Michif/French-speaking people of mixed ancestry — even though many others consider Norquay a Métis leader.

Norquay grew up next to an Indigenous burial ground, was taken under the wing of teachers at the Anglican St. John’s Collegiate School, worked as a teacher, farmer, and fur trader, and traversed the cultures embedded in the six languages he spoke — Bungee, English, French, Cree, Saulteaux, and Dakota — all of which laid the foundation for “different ways of thinking about people with mixed ancestry, about ‘nation,’ and eventually about Canada’s confederation.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

In December 1870, his fellow English-speaking Métis of High Bluff sent him to serve in Manitoba’s first Legislative Assembly after an election he won by acclamation. These were not easy times to be in politics. The small “postage stamp” province was in its infancy, and Louis Riel had fled into exile just before the arrival of Canadian and British troops in August. The Manitoba government was divided into factions: old guard Bungee/English-speaking Métis, Michif/French-speaking Métis, newly arrived Orange Order Ontarians, and Catholic Québécois.

His election was a turning point for the twenty-nine-year-old Norquay, as he accepted the challenges put forth by a role in provincial politics. Friesen notes that leadership “pivoted on quiet conversations and an individual’s ability to express ideas in a forceful, convincing manner,” and he suggests that Norquay’s tutelage in Métis buffalo-hunt protocols serendipitously prepared him for political life.

Between 1870 and 1887, Manitoba’s population grew tenfold. Newcomers inundated the area, bringing outside ideas and a quest for land, along with systemic racism. The new provincial government was controlled mostly by outsiders, not by people native to the Red River Settlement.

Friesen notes that “throughout the 1870s Norquay continued to acknowledge his connections to Cree, Saulteaux, and Dakota neighbours while asserting the distinctive claims of peoples of mixed ancestry.” After he held several ministerial positions, Norquay’s moderate stance on most issues, coupled with his oratory skills, brought him to the forefront. When Premier Robert Davis retired, Norquay formed a new government and became premier in October 1878.

His role as premier was multifold — in addition to tempering the increasingly factional politics in the Legislative Assembly, Norquay worked to define the province’s connection with the federal government in Ottawa. During his premiership he made ten trips to the nation’s capital. As he navigated an undulating relationship with Prime Minister John A. Macdonald and jockeyed for provincial rights within an asymmetrical federal state, Norquay’s expert statecraft made him Manitoba’s first diplomat.

At a time when the average man was five-foot-seven, Norquay stood six feet tall and weighed over three hundred pounds. According to Friesen, at a Conservative Party banquet in 1879 Norquay quipped that Manitoba “might be the smallest province but it had the largest premier.”

He remained premier until 1887, resigning in the wake of a series of scandals. After winning his seat in the 1888 election, his sudden death in 1889 took away his chance to redeem his political reputation.

Collaborator? Yes-man? Quisling? Being a political moderate can bring an assault of adjectives, not all of them complimentary. Regardless, Norquay was the designer, if not the driver, of the basic institutions we have in Manitoba today. Lasting testaments to his work include the expansion of the province’s boundaries; his spadework in the building of roadways and branch railways; the creation of municipalities, court districts, and school districts; and his deft hand in federal-provincial relations.

Friesen, a former professor of history at the University of Manitoba, presents a life and times of John Norquay that is meticulously researched and that is often presented in Norquay’s own words. In doing so, he gives the “engaging ally” and “loving family man” overdue standing in the annals of Canadian history. Leaving nothing in the weeds, Friesen lets readers know that John Norquay is the founder of the Manitoba we know today.

Canada's History magazine was established in 1920 as The Beaver, a Journal of Progress. In its early years, the magazine focused on Canada's fur trade and life in Northern Canada. While Indigenous people were pictured in the magazine, they were rarely identified, and their stories were told by settlers. Today, Canada's History is raising the voices of First Nations, Métis and Inuit by sharing the stories of their past in their own words.

If you believe that stories of Canada’s Indigenous history should be more widely known, help us do more. Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share Indigenous stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!