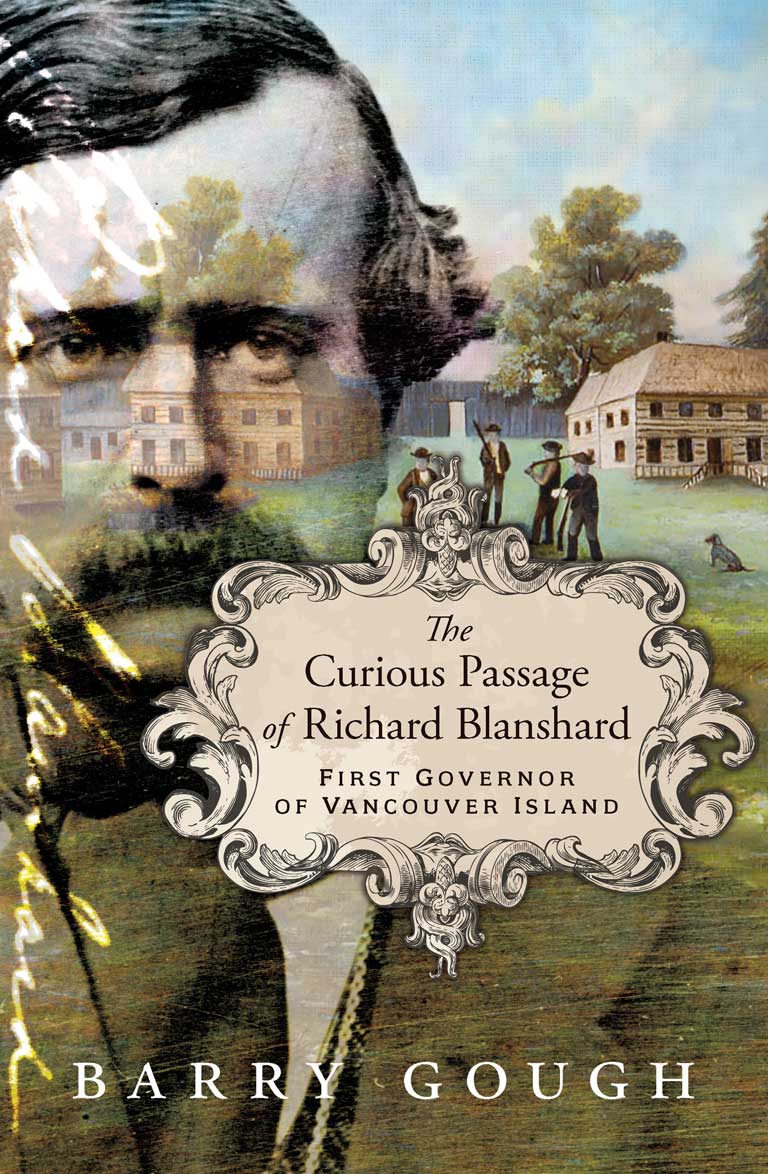

The Curious Passage of Richard Blanshard

The Curious Passage of Richard Blanshard: First Governor of Vancouver Island

by Barry Gough

Harbour Publishing

341 pages, $38.95

The scion of a filthy-rich family of coal barons, shipping magnates, and slaveholding plantation owners, Richard Blanshard found himself in the spring of 1850 homeless on Vancouver Island.

The London, England-bred industrial capitalist had applied for, and won, the position of governor of Britain’s newest overseas colony. But, upon arriving at the Hudson’s Bay Company post of Victoria in early March after a five-month sea voyage, Blanshard discovered that his promised residence had not been constructed. Not only that, but Vancouver Island was a colony without colonists: a fog-swathed, cedar-forested wilderness inhabited by some ten thousand Indigenous people whose language and customs Blanshard did not understand, and by a hundred HBC men who owed far more loyalty to their chief factor, James Douglas, than to the representative of a distant imperial motherland.

This is the absurdity at the heart of the The Curious Passage of Richard Blanshard, a curious tale about a curious personage who forsook his counting house in the British metropolis to take up an unpaid governorship on a distant island, where he “lived a life of exile” with only a single manservant as his staff and “no social club, no upto- date newspapers, and no telegraph or railway.”

The book begins by setting the scene on the Pacific coast in the late 1840s. The newly established border between the United States and British North America was a site of tension and uncertainty, a fluid line through a labyrinth of coastal islands that people on both sides opportunistically violated to nab resources from the other. South of the border, violence raged between settlers, drawn to land and gold, and Indigenous people trying to hold on to their territory and autonomy. North of the border, the HBC — with centuries of commercial and familial relationships with Indigenous people under its sash — generally lived in peace with First Nations.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Seeking to stop American settlers from overrunning the island and provoking violence with Indigenous people, the British government in 1849 created the “Colony of Vancouver’s Island and its Dependencies” and designated the HBC the “true and absolute lords and proprietors” of the island — an arrangement that would last until the company sold the territory back to the Crown in 1867. In exchange, the company promised to people the island with British colonists.

Chief factor Douglas was the company’s original choice for governor of Vancouver Island, but politics intervened to thwart his chances. Instead, British Secretary of State for the Colonies Earl Grey and HBC chairman John Pelly settled on the wealthy and well-connected Blanshard. Trained in the law, the thirtyone- year-old Blanshard had spent most of his adult life in London tending to family business matters. His only experience in the colonies was a stint in India in 1847–49, during which he volunteered with Britain’s Bengal Native Infantry to suppress an uprising against British rule in the Second Sikh War.

Blanshard’s motives in applying for the no-expenses-paid governorship remain unclear. There are indications that he envisaged using Vancouver Island as a stepping stone to positions of greater glory within the Empire. But, although he was the rightful ruler of the colony, he discovered on arrival that the HBC held the de facto power — and that the company had no interest in peopling the island with pesky settlers, nor in helping him to establish civil government.

Advertisement

Barry Gough’s book documents how, over the course of the year 1850, Blanshard’s governorship floundered and the man himself spiralled into a “state of ill health bordering on derangement and fear of death.” Blanshard resigned his position in November 1850 and returned to England the following year, ceding control of the colony to Douglas.

As in his other books, Gough excels at placing local events and individuals in the broader context of the British Empire. He depicts Blanshard in a sympathetic light, portraying him as a competent, well-intentioned man who never stood a chance against the entrenched power of the HBC and its formidable chief factor. A less charitable observer might interpret Blanshard’s trajectory as a classic case of hubris and nemesis — the hubris of a man who presumes to rule a land of which he knows nothing, and his nemesis (punishment and downfall) as he sinks into the morass where he ventured of his own accord.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!