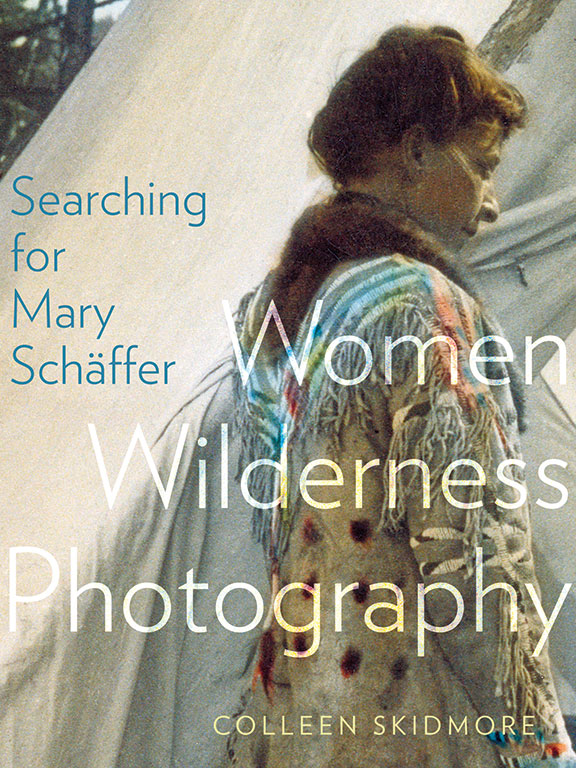

Searching for Mary Schäffer

Searching for Mary Schäffer: Women Wilderness Photography

by Colleen Skidmore

University of Alberta Press, 372 pages, $34.95

Significantly titled Searching for Mary Schäffer, this nuanced study by Colleen Skidmore, a social historian of photography at the University of Alberta, does not claim the final word on Mary Townsend Sharples Schäffer (later Warren), a photographer, writer, botanical artist, and mapmaker known primarily for her work in the Canadian Rockies.

Integrating newly available archival material into a clear, comprehensive, and generously illustrated overview of Schäffer’s life and work, Skidmore covers key issues in women’s history and historiography. She also discusses, with discernment and intelligent scepticism, the ways narrative texts and photographic images can reveal — but also at times conceal or confuse — the facts of biography and history.

Born in 1867 in West Chester, Pennsylvania, Schäffer later settled in Banff, Alberta, near the mountain landscape of her best-known book, Old Indian Trails: Incidents of Camp and Trail Life, Covering Two Years’ Exploration through the Rocky Mountains of Canada (1911).

Schäffer’s writings and “magic lantern lectures,” illustrated with hand-coloured slides, had great popular appeal, feeding those turn-of-the-twentieth-century hungers for “exotic” adventure travel, for a vision of nature as a refuge of moral and physical health, and for the colonial project of mapping, claiming, and controlling territory through rational, scientific study.

Establishing some basic biographical facts, including Schäffer’s explorations of the Rockies and her later trip to Japan with fellow American and frequent travelling partner Mary “Molly” Adams, Skidmore offers a deft overview of the existing work on the photographer. Early reports could be condescending, dismissing her as a dilettante, a socialite, a “Philadelphia lady.”

Later accounts often focussed on her emotional relationships, playing up the mythology that Schäffer’s wilderness excursions were a personal response to the death of her first husband. In fact, Schäffer valued her work as work, and her financial situation was by no means set, as shown by anxious, detailed letters about income and expenses.

Skidmore also challenges the tendency to view Schäffer’s texts and photographs as straight-up documentary evidence, instead viewing her published travel accounts as forms of creative non-fiction that developed the literary persona of “Mary Schäffer,” a self-deprecating and undaunted female traveller who makes light of hardship with wit and spirit.

As Adams wrote in a 1908 letter to a friend: “I kept a diary of facts. Mrs. S. kept one of facts and fiction, very amusing.” Comparing accounts of events by different people, as well as material intended for public consumption with that meant as a private record, Skidmore suggests Schäffer sometimes embellished for the sake of a good narrative, “rather in the spirit of a campfire gathering.”

Skidmore sees Schäffer’s photographs as valuable material artifacts that convey a great deal of information about habits, dress, and dwellings, but she also views them as created works that came about through a complex negotiation between photographer and subject as well as an ongoing collaboration with the viewer. Many of her images, especially those dealing with Indigenous subjects, will be read differently by a contemporary audience.

This is where Skidmore navigates some tricky junctures of intersectional feminism. Schäffer was often disadvantaged as a woman, in her unconventional roles as alpinist, adventure traveller, cartographer, and botanist. But she was also a socially privileged white woman whose view of Indigenous life, though generally sympathetic, shared many of the common colonial prejudices of her era.

As Skidmore points out, Schäffer was credited with “discovering” Maligne Lake, even though she was walking in the Indigenous knowledge of the Iyarhe Nakoda people (then sometimes called Stoney), who had long referred to the lake as Chaba Imne. At the same time, Schäffer’s photograph of her guide, Sampson Beaver, and his family is a striking and complex image that can’t quite be reduced to being an example of the “colonial gaze.”

Interpretations of Schäffer’s work, Skidmore acknowledges, have shifted over time and will continue to be analyzed and contested. “The fact that readers and viewers remain interested in, and at times highly critical of, Schäffer’s works (and Schäffer herself) a century or more later,” she writes, “is testament to the quality, reach, and significance of her images and narratives in her day and our own.”

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement