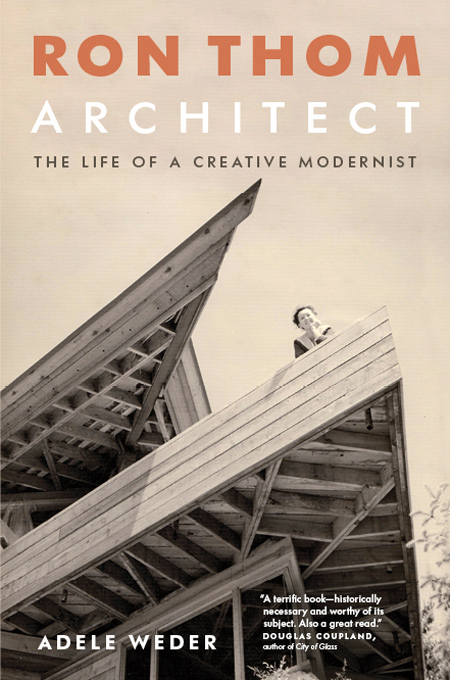

Ron Thom Architect

Ron Thom Architect: The Life of a Creative Modernist

by Adele Weder

Greystone Books

336 pages, $37.95

Charles Edward “Ned” Pratt — an Olympic bronze medallist and principal at the Vancouver architecture firm Sharp and Thompson, Berwick, Pratt — famously separated architects into two categories: “neck-up” and “neck-down.” Neck-up architects, writes Adele Weder, were “practical men … who managed the day-to-day logistics” and worried about plumbing and mechanicals. Neck-downers were “like artists, who felt their way around the design process and relied on gut feelings.”

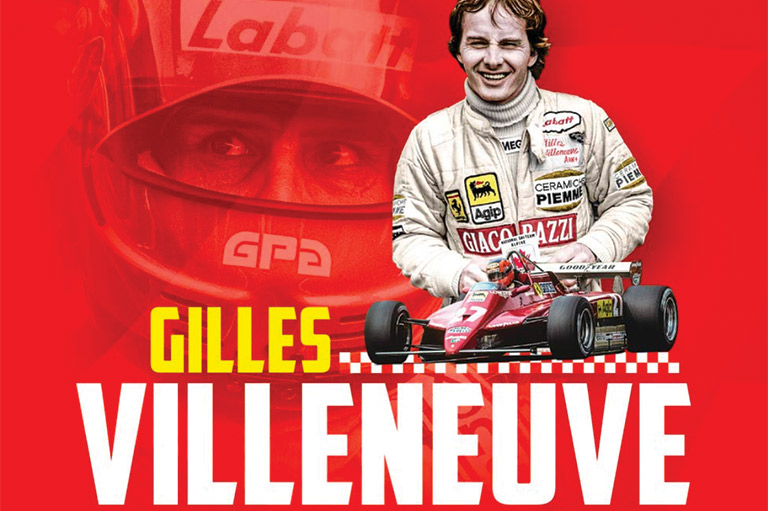

Ronald J. Thom (1923–86), the subject of Weder’s book Ron Thom Architect, was so much about heart, gut, and groin that he could have been the neck-down poster boy.

Through Weder’s detailed research and vivid writing, readers all but smell the ponderosa pines of Penticton, B.C., where the Scotland-born James Thom and his Ontario-born wife Elena — the fourth woman called to the bar in that province — welcome little Ronald into the world, before moving to Vancouver and watching as he almost becomes a concert pianist (but was “a little violent” on the keys), only to find his footing as a visual artist at the Vancouver School of Art. At the VSA, he met instructor Bertram Charles Binning, a semi-abstract artist who would build one of Canada’s first International Style/Modernist houses in 1941.

Joining the Royal Canadian Air Force at nineteen, Ron Thom switched from “social” drinker to “soused,” writes Weder, and married his first wife, Christine Millard. After missing out on combat action, Thom returned to graduate from the VSA. His first child on the way, and in need of a regular paycheque, the young artist was introduced to architect Ned Pratt by his former instructor Binning. In short order Pratt was listing Thom as “design lead” on projects (despite his having no formal architectural training), and by 1950 Thom had designed the entirety of the much-lauded D.H. Copp house, which laid bare his love of American architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

Around this same time, Thom had his first extramarital affair. Major triumphs, such as the B.C. Electric Building or his many house commissions, were counterbalanced by the “domestic battles” with Christine, and by 1961 the couple, now with four children, had divorced. Thom didn’t have time to contemplate his darker side, however, as he was awarded his first Toronto job, the one that would become his masterpiece: the University of Toronto’s monastic, mysterious, and achingly beautiful Massey College.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

On the Massey job, Thom worked closely with graphic designer Allan Fleming — creator of the iconic CN logo — and fell in love with Fleming’s assistant, Molly Golby. After a long-distance relationship, Thom moved to Toronto to marry Golby in 1963. For their honeymoon, the couple travelled to England to research old university buildings for Thom’s next project, Trent University in Peterborough, Ontario.

While Massey College and Trent University are lovingly rendered by Weder’s words — and Thom’s romance with Molly is richly supported by love letters saved by the now ninety-one-year-old woman — it is while documenting Thom’s other Ontario work that the book falls a little flat. The same rich detail about the Shaw Festival Theatre in Niagara-onthe- Lake, the Metro Toronto Zoo, Sir Sandford Fleming College in Peterborough, Atria North in North York, and Toronto’s Prince Hotel is lacking. “The balance is uneven,” agreed Molly Thom when I interviewed her recently. “I expect it’s because Adele is a West Coaster and the work there is accessible and really speaks to her.”

There is also the question of Ron Thom’s alcoholism. While mentioned in passing, Weder gives the impression that it wasn’t entirely an issue until, perhaps, the late 1970s or early 1980s. “Ron’s drinking became a problem for me quite early in our marriage, escalated after the birth of our children" — one, Adam, became an awardwinning architect, which Weder fails to mention — "and was quite serious by the time we moved to Scarborough in 1974,” Molly added. “Associates in the firm had already complained about it, and friends warned that if he continued he would lose his family, his health, and his practice.” Which is exactly what happened.

By choosing to, in Molly Thom’s words, “write discreetly … to avoid giving pain to the family,” Weder has done Canadian history a small disservice. Then again, after Douglas Shadbolt’s 1995 book Ron Thom: The Shaping of an Architect painted too gloomy a portrait, Weder, at least, has pinned Thom’s elusive beauty like a butterfly under glass — at the risk of coming off as a bit of an acolyte. “What demon caused him to throw everything away, including his reputation?” Molly Thom asked. The answer to that, unfortunately, likely lies in the ether, unobtainable by the written word.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement