Prairie Interlace

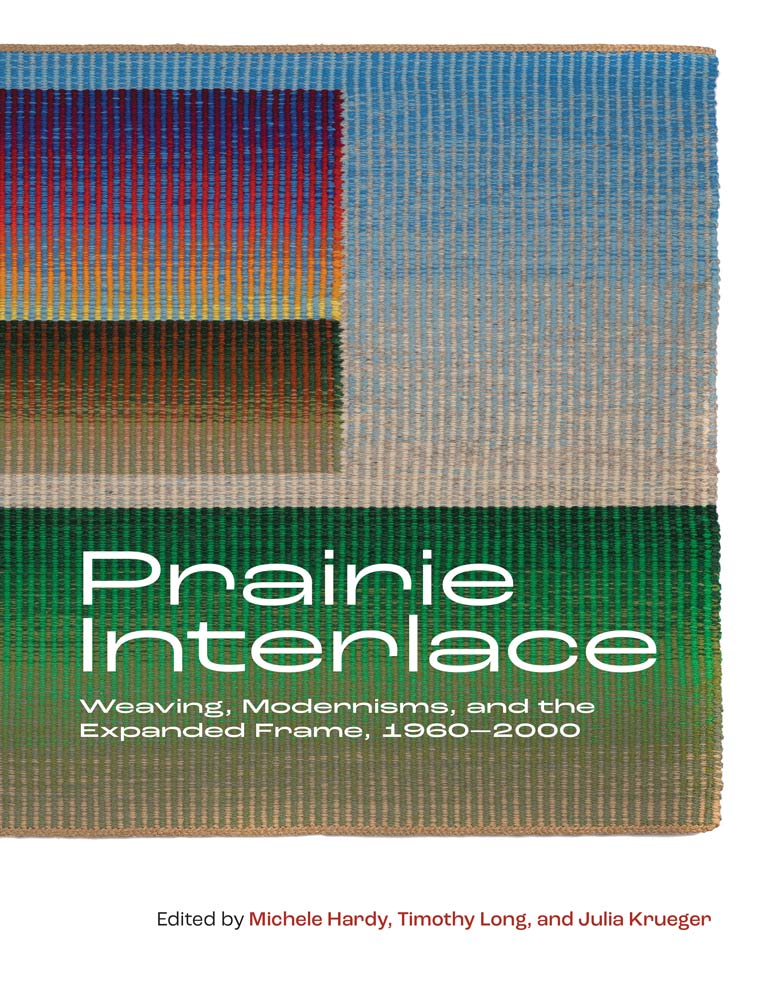

Prairie Interlace: Weaving, Modernisms, and the Expanded Frame, 1960–2000

edited by Michele Hardy, Timothy Long, and Julia Krueger

University of Calgary Press

248 pages, $59.99

A double review with

Weaving Modernist Art: The Life and Work of Mariette Rousseau-Vermette

by Anne Newlands

Firefly Books

192 pages, $49.95

Two recent books delve into the fascinating but overlooked history of the textile-arts scene in Canada. Through the postwar years and into the 1970s and 1980s, this unique art medium burgeoned in popularity — distinctive large-scale tapestries and weavings became valued additions to private and public art collections, while commissioned works graced the lobbies and interiors of major buildings.

Many of the practising textile artists were women. As noted in the introduction to Prairie Interlace, these were weavers who “harnessed scale to challenge fibre’s stereotypical associations with utilitarian craft and domesticity.” The book is a companion piece to a symposium, a website, and a travelling exhibition that feature more than sixty artworks by forty-eight artists. It was edited by curators Michele Hardy, Timothy Long, and Julia Krueger through Nickle Galleries at the University of Calgary and the MacKenzie Art Gallery in Regina.

Overall, the project foregrounds “ancestry” over “legacy” in order to “recover and record lost modernisms,” according to contributor Jennifer E. Salahub, a professor emerita of art, craft, and design history at the Alberta University of the Arts. Included in the book are essays about Metis and other Indigenous women textile artists in Saskatchewan. Several of their vibrant, woven-rug artworks were included in the exhibition.

Readers who are unfamiliar with fibre-arts history are rewarded with a veritable cornucopia of images that show striking, exuberant, and astonishingly innovative artworks. Many works are seen in situ — whether in historical photographs or as installed in the exhibition — thereby providing a clear sense of their scale and impact.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

A number of pieces fall recognizably within what is known as prairie modernism. They employ serene grid lines or allude to nature; they gesture to the near-abstraction of horizon, that “destination to which one may never arrive,” as described by contributor Mackenzie Kelly-Frere. Pat Adams’ woven wall hanging Prairie Sunset (1983) shimmers magically with refracted colours of land and sky, while Margaret Sutherland’s vertical weaving The Seed (1984) flows in a calming grid of earthy buffs and browns.

Fabric works such as these softened the concrete used in modernist buildings and in other public spaces. Kaija Sanelma Harris’s spectacular series of twenty-four coloured tapestry panels, called Sun Ascending, was originally installed in the foyer of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s TD Bank Tower in Toronto, while Susan Barton-Tait’s enormous three-dimensional weaving Northern Lights created a colourful vista in Winnipeg’s Manulife Building.

However, the woven artworks also moved beyond abstracted landscapes. The book mentions the ways many of these artists challenged colonialist paradigms of “empty” prairie landscapes, narrow ideas about “high” art, and the clean aesthetic and strong lines of modernist art — from which, as the curators point out, their art was often excluded.

This art was exhilarating. It drew on crafting traditions and underscored women’s labour and social issues; it championed ornament or overflowed frames, refusing to lie flat against walls. Inventive pieces that transformed weaving into sculpture include Charlotte Lindgren’s spare and haunting woven hanging Winter Tree (1965) and her dramatic work Aedicule, a large architectural structure of draped red mohair, wool, synthetic, and silk. Pieces like Margreet van Walsem’s Birth (1971) incorporated female bodily imagery, sometimes humorously and frequently with a feminist lens.

Prairie Interlace elucidates the forgotten contexts that fostered textile artists and cultivated the fibre arts movement on the prairies. One particularly noteworthy development was the ground-breaking program formed in 1941 at the Banff School of Fine Arts. Artist Ines Birstins recalled that, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, its Fibre Studio under the leadership of visionary Quebec weaver-artist Mariette Rousseau-Vermette was “the most exciting place you could ever imagine.”

Anne Newlands’ book Weaving Modernist Art tells the story from another angle and serves as an ideal complement to Prairie Interlace. Her subject, Rousseau-Vermette (1926‒2006), was one of the most celebrated and successful Canadian artists of her time — but, like many of these creators, she has been largely overlooked within art history.

An independent curator who worked for almost three decades as a researcher and writer at the National Gallery of Canada, Newlands has a special interest in Rousseau-Vermette. She seeks to share the stories and experiences of women artists “who deserve to be better known” and “textile artists in particular who have been sidelined in histories and exhibitions of Canadian art.”

Weaving Modernist Art skilfully recounts the excitement around textile arts as a form of creative expression through the postwar years into the 1960s and the “fibre revolution” of the seventies — including the significance of the work having been recognized alongside painting and other media at the time.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

For Rousseau-Vermette, there were collaborations with artists and architects (including Arthur Erikson); exhibitions in her home province of Quebec as well as nationally and abroad, including at the inaugural International Biennial of Tapestry in Switzerland in 1962; and commissioned private pieces and major public installations at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the National Arts Centre in Ottawa, Place des Arts in Montreal, and elsewhere.

Another interesting aspect of the book is how Newlands situates Rousseau- Vermette’s work and career within the wider history of weaving, as well as in relation to social and economic forces within Quebec and Canada.

Rousseau-Vermette acknowledged her debt “to the artisanal traditions of weaving in rural Quebec.” As these traditions declined in the early twentieth century, the Canadian Handicrafts Guild in Montreal worked to revive them. Following the global economic crisis of 1930, a program was established to expand domestic-arts skills through the Quebec teaching system. Rousseau-Vermette’s mother was president of a domestic-skills-sharing organization for rural women, as well as an amateur painter, and introduced her to the loom. Then the Quiet Revolution propelled a sense of freedom and buoyed creative expression, as Quebec society broke from the restrictive ideologies of the Catholic clergy and the repressive regime of the Duplessis government.

Like Prairie Interlace, Weaving Modernist Art captivates through its images. Even leafing through the book lends an appreciation for the immensity and magnificence of Rousseau- Vermette’s works. They include her glorious, massive masterpiece of suspended tubes swathed in knitted and felted wool that was installed in Toronto’s Roy Thomson Hall — before later, somewhat shockingly, being lost to short-sighted renovation plans.

Her 1977 entry for the International Biennial of Tapestry, Harmonia, is an impressive wall work of 150 aluminum tubes covered with knitted wool in a range of colours. A Swiss art critic then described it as “a marvellous ode to joy.” And so it is, along with this book.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement