Pier 21

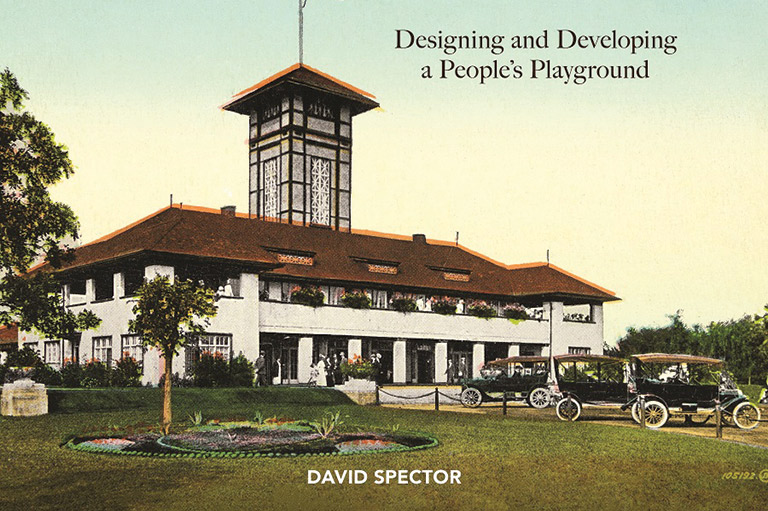

Pier 21: A History

by Steven Schwinghamer and Jan Raska

University of Ottawa Press

276 pages, $27.95

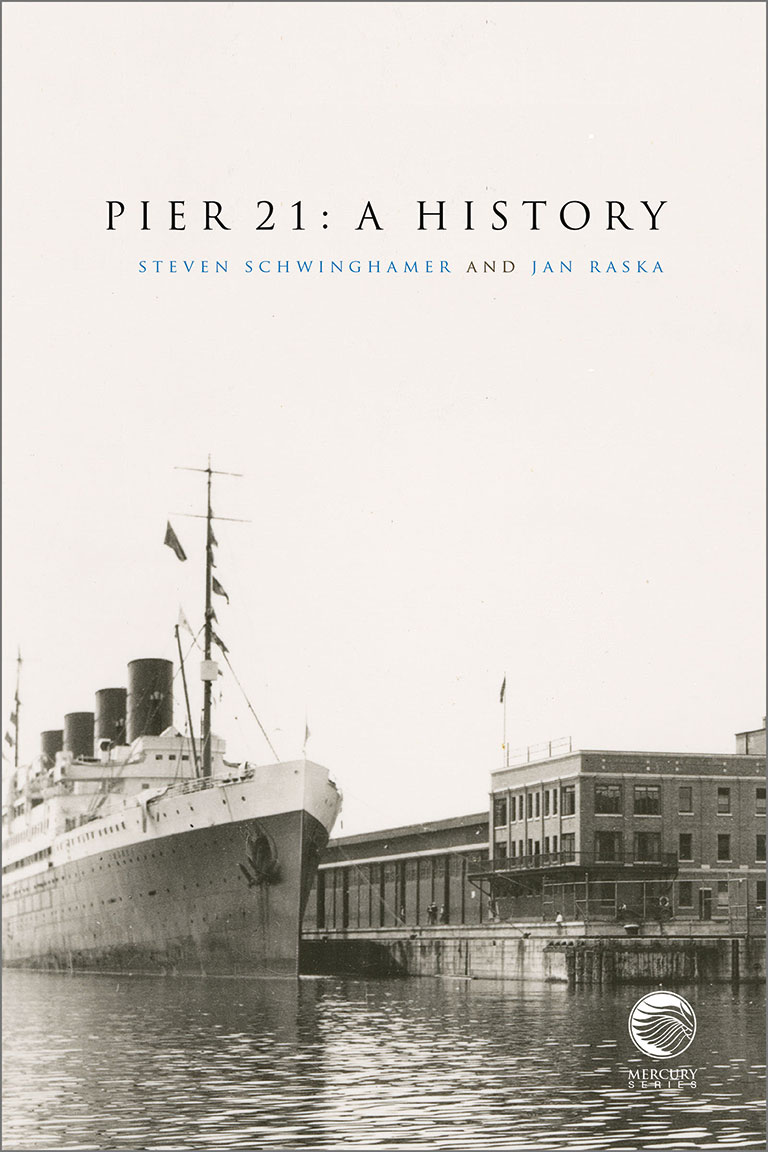

If you could pick a Canadian building and hear its walls talk, which one would you choose? Province House in Charlottetown? The Montreal Forum? The Banff Springs hotel? It’s hard to think of a building that would have more or better tales to tell than Pier 21 in Halifax. Those personal stories are what lift Pier 21: A History above a simple recounting of the immigration facility’s past.

The authors recount a list of delays, inter-agency miscues, labour problems, and wartime austerity measures that prolonged the construction of Pier 21 for thirteen years (cost overruns and unmet deadlines not being exclusively modern phenomena). But, when the new facility finally opened in 1928, so too did an important chapter in the story of Canada.

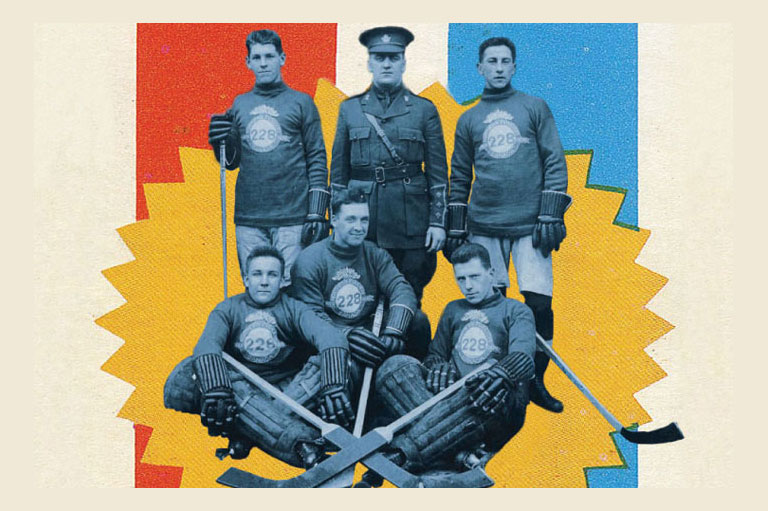

Pier 21 served as a critical military hub, sending personnel and supplies to Europe and receiving prisoners of war and merchant mariners from abroad. Its postwar years saw a boom in immigrants and refugees entering Canada from displaced persons and Baltic refugees to Jewish war orphans.

Tens of thousands of people in search of a better life disembarked, boarded trains, and spread out across the country, often completely unaware of what to expect. Celina Lieberman, a Jewish orphan from Poland, said she arrived in Halifax in 1948 “without a family or a country.” Lieberman added: “All I was told was that I was going to Regina, Saskatchewan, presumably to a Jewish family, but I was not sure.”

Co-authors Steven Schwinghamer and Jan Raska describe people who were driven by oppression and political upheaval to Pier 21 — including Hungarians fleeing Soviet invaders in the mid-1950s, followed shortly afterwards by Cubans who opposed Fidel Castro and, a decade later, refugees from Czechoslovakia’s Prague Spring. The authors also highlight the work of volunteers who provided comfort, such as the Roman Catholic Sisters of Service, who offered spiritual support and practical necessities, and United Church members who distributed “ditty bags” containing toiletries, candy, stationery, and stamps.

Details enliven the book and create vivid sensory images. Italian children rejected a bologna sandwich on white bread, finding the processed food too sweet. Dutch women dried hand-washed diapers on a line strung in a train car. An English girl marvelled at the lights of Halifax that, she said, were shining “like a miracle.” Even the authors’ accounts of medical screenings, the interview process, and life in the dormitories are descriptive and move briskly. Pier 21 also contains many excellent black-and-white photographs.

The book grapples with the unpleasant reality of Canada’s long-enduring attitudes towards immigrants and refugees, including the determination of who was desirable (typically white English, Irish, and Scottish immigrants) and who was not (Jews, Asians, and people with intellectual or physical disabilities) when it came to preserving, as Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King famously said, “the character of our population.” Whether officially enacted in racist legislation or simply enforced by garden-variety bigots, such judgments provide a bitter counterpoint to the more palatable stories of freedom and new beginnings.

With the opening of the Halifax International Airport in 1960, the numbers of immigrants arriving through Pier 21 declined sharply. It closed as an immigration facility in 1971. The building took on a new life as an interpretive centre and is today the main entrance to the Canadian Museum of Immigration, where both authors are historians. The museum is itself a fascinating place to visit and offers a wealth of archival information about the many people who entered Canada through Pier 21.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement