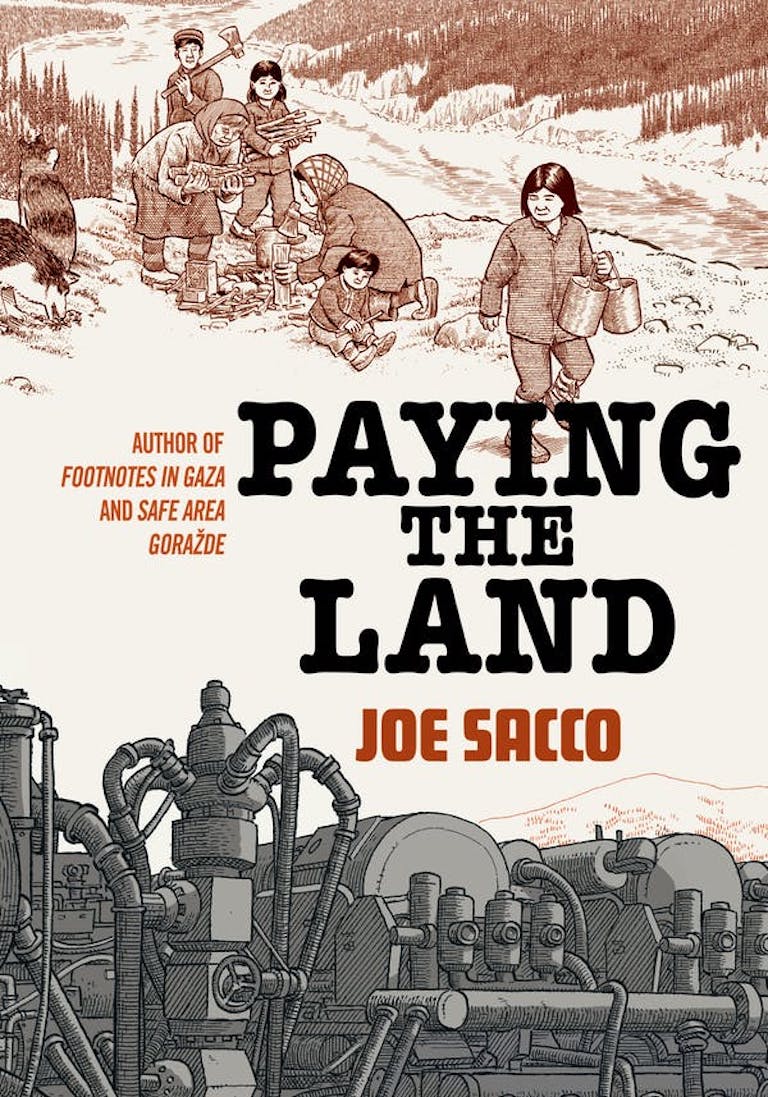

Paying the Land

Paying the Land

by Joe Sacco

Metropolitan Books,

272 pages, $39.99

If it seems difficult to imagine how a white man who was born in Europe and lives in the United States could create a moving, complex history of Dene life in the Northwest Territories over the past half century, just wait — it gets better. Joe Sacco manages to do all of that ... in monochrome comics.

But despite all the reasons why Paying the Land shouldn’t work, this graphic novel is in fact a breathtaking book that all Canadians would benefit from reading. It powerfully illuminates the dignity of life on the land, that life’s near destruction by outside forces, and the possibility of resurgence. The vast majority of the text comes directly from interviews with a range of Dene politicians, activists, and ordinary people as well as a few non-Indigenous observers. Sacco includes himself as a secondary character, mostly to highlight his ignorance, to fill in detail, or to move the story to a new time or location.

The focus, though, stays firmly on the Dene, presenting their experiences in their own blunt, devastating words. The book starts with a portrait of a community intimately connected to its territory, as Paul Andrew remembers it. People fish, hunt, set up camp, celebrate — all of it done together, the children learning by watching and listening as everyone plays a role. Without romanticism, Sacco deftly conveys both the hard work that is required and the beauty of a communal culture almost completely separate from Canada.

That life and that separation cannot, of course, continue. Soon the focus shifts to the encroachment of European colonizers who are keen on the rich resources the Dene have stewarded since time immemorial. Treaties and furs, mines and the doctrine of discovery, roads and diamonds, and alcohol and pipelines slowly, sickeningly work to corrupt the circle of community.

Sacco weaves together the narrators’ stories, moving back and forth through time while capturing a look or a posture that says much more than words ever could. Marie Wilson, who was one of three commissioners of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, flatly describes five-year-olds being raped on their first day at a residential school by older children who had been cut off from family and from their culture’s ideas of collective well-being. Those children then somehow had to figure out how to live with each other back home.

Perhaps the book’s greatest strength is its insistence on avoiding easy answers. Sacco literally illustrates the differing points of view among the Dene about how to handle resource extraction and land claims, laying out the agonizing complexity for readers but pushing no particular conclusions. He includes an interview with a genuinely kind priest, one with a residential school survivor who expresses appreciation for the chance to learn English, and another with a young woman who criticizes the lack of initiative among the men of her age. Throughout, Sacco highlights each person’s humanity, keenly aware of the history of people like him coming north to take without giving.

Indeed, his scorn is provoked by what he learns on a tour of the defunct Giant Mine, whose gold-mining legacy includes more than two hundred thousand tonnes of arsenic. He is told that the lethal waste is contained for a good one hundred years or so. “What is the world view of a people who mumble no thanks or prayers,” he writes over ever-darker panels, “who take what they want from the land, and pay it back with arsenic?”

It would undermine the book’s integrity to describe the ending as happy — there is no neat resolution, and nor should there be. After having met thoughtful young Dene activists and having seen the persistence of some traditional ways, the reader can only marvel at the most important conclusion of all: that, after all they have been subjected to, the Dene are still here, still vital, still connected to their territory.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement