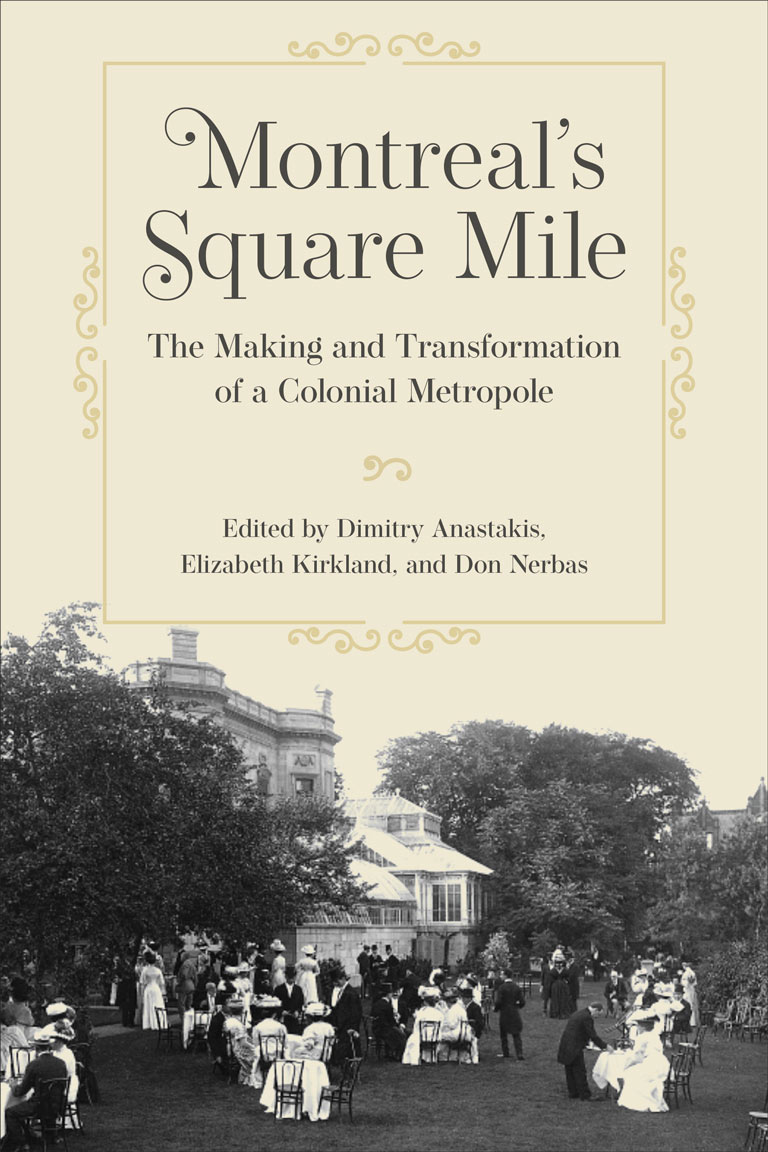

Montreal’s Square Mile

Montreal’s Square Mile: The Making and Transformation of a Colonial Metropole

edited by Dimitry Anastakis, Elizabeth Kirkland, and Don Nerbas

University of Toronto Press

464 pages, $39.95

A double review with

Casa Loma: Millionaires, Medievalism, and Modernity in Toronto’s Gilded Age

edited by Matthew M. Reeve and Michael Windover

McGill-Queen’s University Press

336 pages, $49.95

As Canadian society grapples intensely with its colonial past, two new essay collections bring us back to a time and place when imperialism determined the nation’s dominant values and, consequently, its architecture. Land grabbing, resource extraction, and fur trading swiftly made a good number of the new immigrants very rich and left them in need of homes that would boast of their wealth and status. In texts, photographs, and historic documents, the two books chronicle an arriviste’s castle in Toronto and a square mile of upper-crust housing in Montreal — hundreds of kilometres apart geographically, but very close in terms of their roles in our socioeconomic history.

Casa Loma is nominally focused on one man’s house, whereas Montreal’s Square Mile describes the urban matrix of its titular subject. But both books also describe entire neighbourhoods — entire cities, even — and the people who lived there. These enclaves of wealth housed the newly minted or soon-to-be elites. As essayist Roderick MacLeod observes in his contribution to Montreal’s Square Mile, in the centrifuge of social status certain Montrealers elevated their status and power simply by living there.

The square mile built up in the nineteenth century at the base of Montreal’s Mont Royal brought together the city’s haute bourgeoisie. Also known by its more unctuous nickname, the “Golden Square Mile,” the neighbourhood and much of its architecture still exists. It’s now a checkerboard of old and new, interlaced with contemporary public buildings and the ever-evolving campus of McGill University; but enough has survived to serve as a repository of architectural history and culture.

Around the same time that Montreal’s elites were scrambling for a stake in the Square Mile, a panoply of mansions sprouted up along the Davenport Ridge in what is now central Toronto. The pinnacle of this millionaire’s row was a two-hundred-thousandsquare- foot ensemble of castle, stables, servants’ quarters, and outbuildings — all for the family home of Sir Henry Pellatt. “Casa Loma is not merely a big house,” Pellatt asserted in a 1924 newspaper interview. “It is an architectural museum, something absolutely unique, the union, as it were, of the fortress architecture of the ages.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Designed by architect E.J. Lennox and completed in 1914, Casa Loma would go on to have a tumultuous history that in many ways reflects the undulating conventions of Ontario society in general. By the mid-1930s, Pellatt — who had grown rich by investing in the province’s hydroelectricity industry — had lost his fortune. Casa Loma was seized by the city for unpaid taxes, prompting an extended period of public debate about how much of it — if anything at all — should be saved for posterity.

Today the main castle is in decent shape, recently renovated, and respected — though hardly revered to the extent that Pellatt aspired. It is a tourist attraction, available to gawk at or to rent for weddings, parties, and movie sets, a very twenty-first-century fate for a century-old building.

As with Casa Loma, many of the Square Mile buildings were over-thetop in their ornamental excess — but, as MacLeod writes, ostentation was the goal. Even as the first seeds of Modernism were sprouting on the other side of the Atlantic, the upper crust of the New World still relied on corbels, cornices, columns, and every other kind of detail to advertise their wealth. Interestingly, both books at times suggest that this neoclassical building frenzy signalled a kind of beginning for a homegrown Canadian architecture. For this reader, the subject matter is more about the intense last gasps of architectural colonialism.

MacLeod, Annmarie Adams, and other contributors to Montreal’s Square Mile unpack the demographic and gender-related underpinnings and marginalizations embedded in the built landscape of that elite neighbourhood. Casa Loma is more physically descriptive, offering exhaustingly detailed descriptions of the mansion’s architecture, interior design, and construction. So be it: There is more than one way to unpack our built history, although architecture is always a kind of biography of the individuals and the society that have created it.

Both of these essay collections are fine contributions to our understanding not only of architectural history but also regarding the entangled matrix of political, economic, and social histories. Filled with vintage photos and renderings, as well as insightful texts from an array of scholarly minds, the books expand our understanding of architectural history. But arguably more pertinent is the larger story they unpack: about power, ostentation, and the Ozymandian need to write one’s name in the sand.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!