Love Story

In 1944 Vivian Keeler, an attractive, vivacious young white woman with deep roots in Nova Scotia, met Billy White, a charismatic member of a prominent Black family, at a Halifax lunch counter. Their mutual attraction turned to friendship, then courtship, a move to Toronto, marriage, and children — but not without obstacles that the bigotry of that time threw in their way.

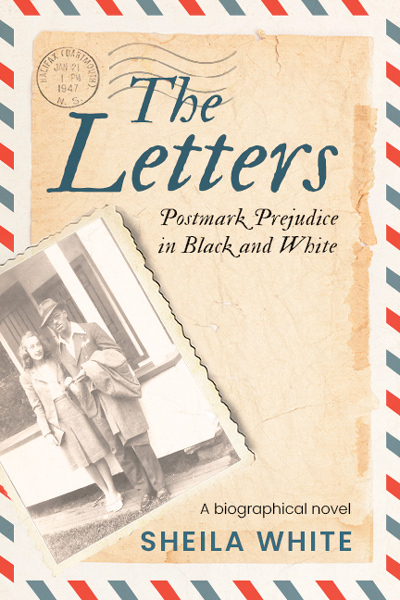

Their daughter Sheila White wrote The Letters: Postmark Prejudice in Black and White, a biographical novel that chronicles her parents’ struggles to stay together in the face of an orchestrated letter-writing campaign to keep them apart.

Canada’s History contributing editor Nelle Oosterom spoke with Sheila White about her book.

What inspired you to write this book?

The letters that my mother saved for seventy years had been kicking around for some time. She introduced the letters to her children and told us the story when we were very young, about how her mother didn’t want her to marry a Black man and had arranged for all these letters to be written by her friends and relatives. I felt that it was up to me to bring the letters and what they stood for to light. I felt it was a story of love, and courage, and positive race relations.

Your parents met and dated in Halifax in 1944. What was that like for them?

It was a unique situation because Billy’s family had a famous pedigree. [World-renowned contralto Portia White was Billy’s older sister]. He was extremely popular, and their coming together was not as complicated as for others, because of his stature. But still, they had to meet in restaurants or public places. It wasn’t that Vivian could say, “Come to my place.” There was no open invitation into the home.

Many of the letters your mother received in Toronto just prior to marrying Billy argued that their children would not be accepted by anyone. Did you and your four siblings feel like outcasts?

No, actually we were pretty popular kids. We all met with our own version of success. We all had wonderful recollections of our childhood. So that was all bunk, these racist ideas.

Your father received the Order of Canada in 1970 for his work as a social worker, activist, and musician. He could take a room full of people and have them singing four-part harmony in minutes. How important was music to his work of bringing people together?

I’m telling you, music dispels borders and boundaries faster than anything else. You can’t be in a room singing with people and feeling anything but love and joy. Once you have those two components activated, it’s very hard for hate to survive.

What would you like people to take away from reading this book?

The core message is that racism can be defeated. We need to explore the shopping basket of techniques at our disposal to make that happen. I would just like to show that all that time ago — in the forties, and fifties, and sixties — there were things being done that were making human relations more palatable for everyone.

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.