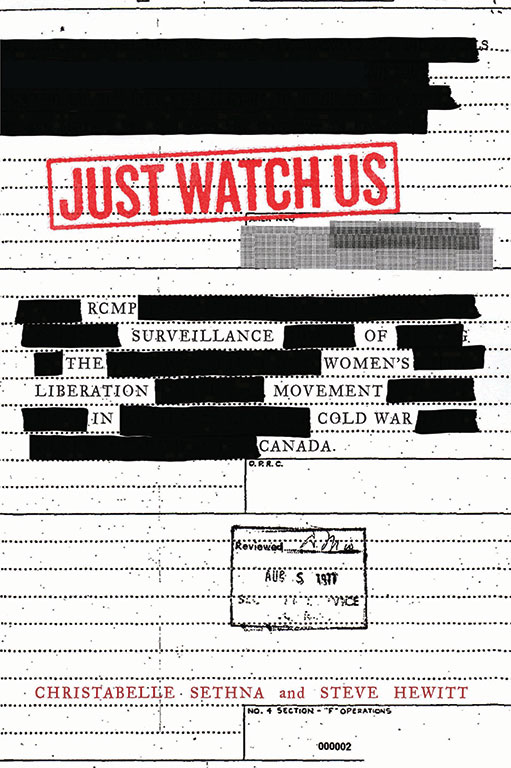

Just Watch Us

Just Watch Us: RCMP Surveillance of the Women’s Liberation Movement in Cold War Canada

by Christabelle Sethna and Steve Hewitt

McGill-Queen’s University Press, 316 pages, $34.95

A double review with

Spying on Canadians: The Royal Canadian Mounted Police Security Service and the Origins of the Long Cold War

by Gregory S. Kealey

University of Toronto Press, 286 pages, $29.95

It’s not paranoia if they actually are out to get you, and readers of two new books about the history of the RCMP’s security service may very well conclude that they are.

Christabelle Sethna and Steve Hewitt’s Just Watch Us examines RCMP surveillance of the “second wave” feminist movement in Canada over a fifteen-year period beginning in the late 1960s.

The core argument of their work is that the RCMP saw the women’s liberation movement through the lens of what the authors call a “red-tinged prism.” Largely ignorant of feminism and the authentically radical demands of the women’s movement, the RCMP instead searched for phantom communists in the movement’s ranks.

This in turn was part of a broader effort in the late sixties and the seventies to root out “red” influences in the New Left and its attendant social movements.

The RCMP’s activities, the authors note, should be of particular concern to Canadians, as the organization invariably targeted and further alienated already marginalized groups. Moreover, surveillance data was gathered not merely for its own sake but for its potential to disrupt, harass, and otherwise repress those communities when the government deemed it necessary to do so.

While Sethna and Hewitt focus on a period of about two decades, Gregory Kealey’s collection of essays, Spying on Canadians, ranges more freely. Forging links between the history of the security service and working-class Canadians, Kealey argues that unwarranted and often-paranoid domestic surveillance and, at times, outright repression have very deep historical roots, predating the creation of the RCMP and reaching back to the beginning of Canadian statehood.

These activities have been persistent over time but have waxed and waned with the times, intensifying in times of war, including during the Cold War and pseudo-wars — such as the “war on terror.”

Kealey’s essays, while scholarly and academic in tone, are not beyond reach for non-specialists. They focus in particular on the repression of labour and “suspect” immigrant groups. Of particular importance, as Canadians commemorate the end of the First World War, are Kealey’s essays on the repression of these same communities in wartime.

These chapters raise serious challenges to the uncritical claims, made too often at commemorative events, that the world wars were fought entirely to defend freedom and democracy.

Kealey’s essays were written between 1988 and 2003. It is something of a minor miracle that University of Toronto Press agreed to print a collection of papers that have been published elsewhere. But the force of Kealey’s indictment — and it is that — is greater when his essays are considered together.

The authors of both works, and Kealey in particular, stress that the issue is not merely passive surveillance but the violation of fundamental civil liberties. Kealey provides ample evidence of egregious acts of repression, directed in particular at organized labour, by the RCMP and its predecessors.

In their book, Sethna and Hewitt note that the redaction and outright destruction of certain records has made it impossible to discount the possibility that the RCMP carried out more serious acts of direct repression against the women’s movement and other New Left groups in the sixties and seventies.

Similarly — in two concluding chapters and an appendix that I urgently recommend to classes on historical method — Kealey writes at length about the trials, tribulations, and, indeed, risks involved in seeking access to information. As late as the mid-1980s, CSIS cited security concerns in attempting to deny his access to records from 1919 and 1920!

In their respective books, these writers emphasize that the history of the security service’s actions must be understood, lest renewed transgressions of the law and of the rights of Canadians be viewed as an aberration.

I began this review with a mild joke, but this is no joking matter. The RCMP’s domestic surveillance activities, of course, were not unique: American and British security services engaged in parallel acts and comparable acts of repression. But the revelation of these activities will surprise many Canadians and may even seem like an affront to others.

The current political situation in the United States, where the president himself has impugned the loyalty of the intelligence community, has resulted in the paradoxical sight of progressives rushing to the defence of the FBI and other national security agencies whose agendas they have in the past vehemently condemned.

Similarly, many Canadians today admire the bravery of members of the RCMP, embrace the myth of the agency’s nobility, and associate its uniforms and pageantry with Canadian identity. But, in their respective works, Kealey and Sethna and Hewitt have established a devastating counter-narrative: that of an RCMP that for decades imperilled the rights of Canadians whose security it purported to defend.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement