Into the Light

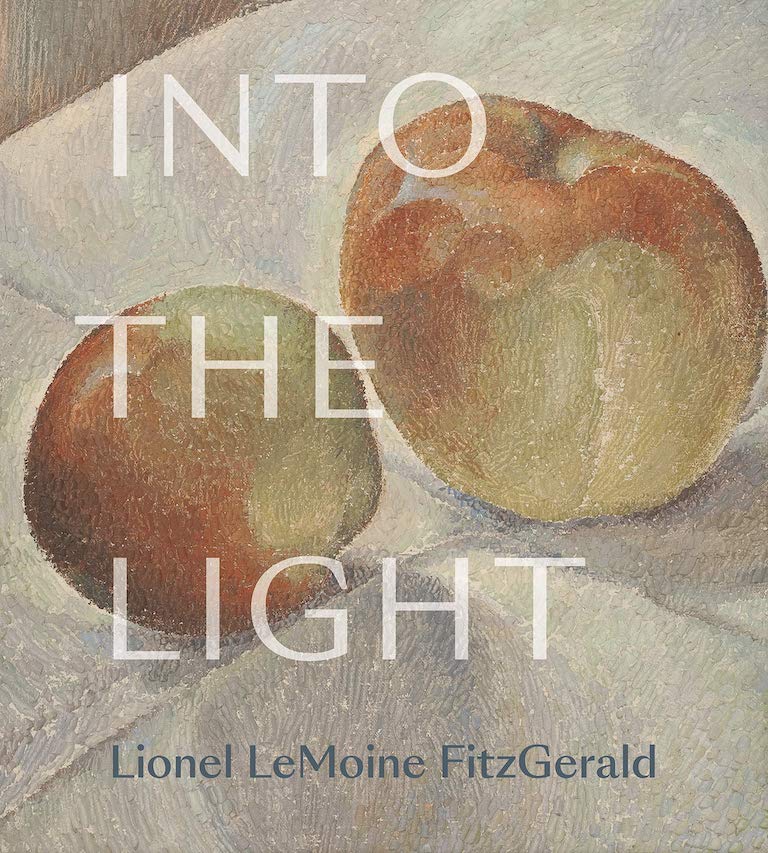

Into the Light: Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald

by Sarah Milroy, Ian A.C. Dejardin, and Michael Parke-Taylor

Figure 1 Publishing,

248 pages, $60

Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald is the least famous member of Canada’s most famous artists’ association. He joined the Group of Seven in 1932, but his patient, pellucid work has never received the attention it deserves. Into the Light, released alongside a major exhibition organized by the McMichael Canadian Art Collection and the Winnipeg Art Gallery, is a long-overdue examination of the Manitoba artist’s life and work.

It’s not just that FitzGerald joined the group late, only a few months before it disbanded. FitzGerald has been overlooked for other reasons. His genius was idiosyncratic and individual, not easily absorbed into the triumphant nation-building myths that surrounded the Group of Seven. While other members were known for iconic paintings of rugged rocks and pines, realized through intense colour and big brush strokes, FitzGerald’s poetic, precise style relied on line. He also painted the prairies — a landscape mostly ignored by the group — exploring its long, low horizons and subtle tonalities.

The text in this well-designed book combines hard research — filling in biographical gaps, tracking cultural influences and stylistic developments — with insightful analyses and evocative personal responses. Exhibition co-curator Sarah Milroy begins with a description of a small FitzGerald drawing — an utterly pared-down study of two blades of grass — and many of the book’s pieces are, likewise, elegant compressions of larger concepts.

Born in Winnipeg in 1890, FitzGerald grew up spending time on his grandmother’s farm near Snowflake, Manitoba. Winnipeg Art Gallery director and CEO Stephen Borys writes of FitzGerald’s deep connections to the cultural landscape of Manitoba, through both the gallery and the related Winnipeg School of Art. Many of the scenes FitzGerald painted, such as in the well-known Doc Snyder’s House, would be immediately recognizable to his hometown fans — winter views of snowbound yards, back lanes, fences, and garages.

He may seem like a regionalist artist, then. But Andrew Kear, in an essay rethinking FitzGerald’s early career, and Michael Parke-Taylor, in a piece examining a pivotal trip to the United States in 1930, demonstrate how the artist absorbed, adapted, and reworked international influences, channelling his observation of the Manitoba landscape through Cezanne, Seurat, and the American Precisionists.

Though FitzGerald worked mostly in the traditional genres of landscape and still life, he was a curious and tireless experimenter, often exploring the ground between representation and abstraction. Oliver A.I. Botar looks at some of FitzGerald’s erotically charged drawings and watercolours, enigmatic and inward-looking works he describes as “explicit without being pornographic.” Botar relates them to biocentrism, a confluence of scientific, spiritual, and philosophical ideas about the life force that circulated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Photographer Geoffrey James speaks of FitzGerald as a “painter’s painter,” and Into the Light features several artists responding to specific works. Robert Houle, who grew up in Kaa-wii-kwe-tawang-kak (Sandy Bay First Nation) on the shore of Lake Manitoba, connects the towering skies of Prairie Landscape to memories of storms coming in over the water. Wanda Koop recalls seeing Poplar Woods and recognizing, even as a child, that “it wasn’t quite about trees.”

The book includes long sections of visuals unbroken by text, a design decision that encourages the kind of close, patient looking these works require. There are hushed still lifes touched with inner light and living, breathing gold-and-green landscapes. A lot of attention is given to drawings and sketches, something that’s crucial with a master draughtsman like FitzGerald.

Though aspects of this private and somewhat solitary man’s life remain elusive, art historian Parke-Taylor has pulled together an extensive and illuminating chronology. The further-reading list, on the other hand, is brief — and not for want of trying.

Into the Light is a much-needed corrective to what has been a relative scarcity of writing on FitzGerald. Full of the kind of thoughtful, complex responses that FitzGerald’s art, in its own subtle power, seems to call forth, it is both an important academic resource and a good-looking opportunity for coffee-table-book browsing pleasure.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement