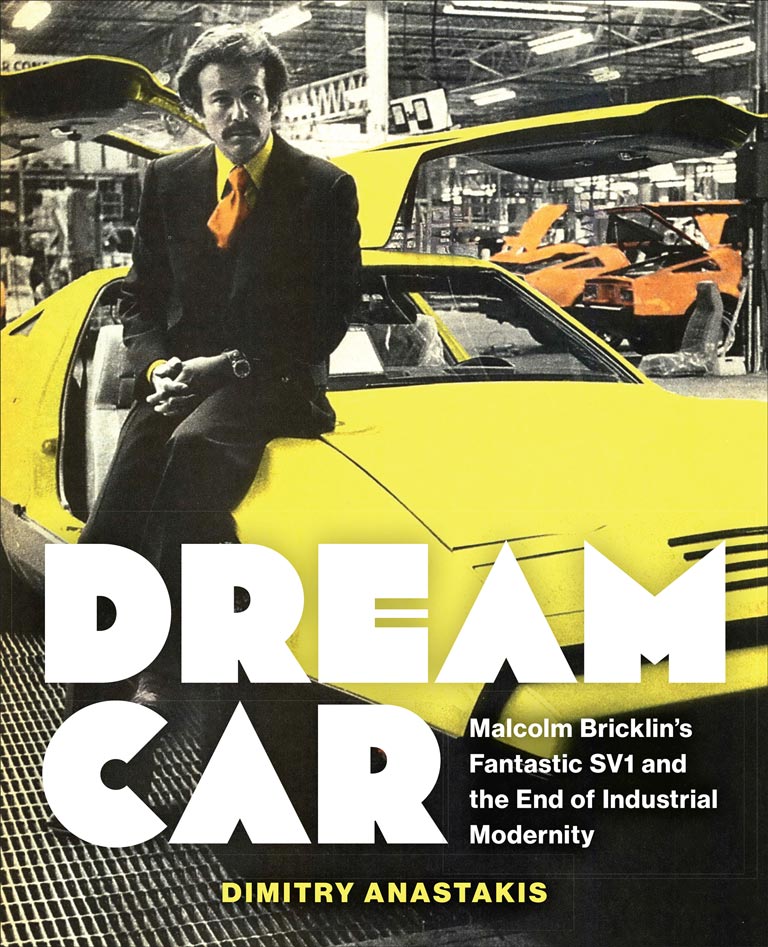

Dream Car

Dream Car: Malcolm Bricklin’s Fantastic SV1 and the End of Industrial Modernity

by Dimitry Anastakis

University of Toronto Press

450 pages, $39.95

Of all the costly scandals and taxpayer-funded boondoggles in recent New Brunswick history, only one elicits a wistful sigh or a hint of pride. That was the Bricklin, the 1970s-era sports car built in the province and shepherded into existence by two iconoclastic men decidedly of their time — serial huckster Malcolm Bricklin and flamboyant politician Richard Hatfield, the province’s longest-serving premier. Within two years, the venture failed and the car became a punchline, a memorable symbol of government hubris. “If you’re going to have a politically embarrassing failure,” Hatfield once declared, “it should be something you have a lot of fun with.”

Hatfield had a lot of fun with the Bricklin, driving the car around the province to summer festivals and making it, literally, the vehicle of his 1974 re-election campaign. Dimitry Anastakis has fun with it, too, in this engaging story of the infamous car and its makers. Anastakis positions the Bricklin not only in the context of automotive history but also of pop culture, sexuality, and political philosophy.

After a slightly overlong prologue and introduction, Dream Car accelerates to a thrilling speed. The car lore is strong here. Anastakis, a professor of business history, understands the broad cultural currents that shaped the car-manufacturing sector and gave rise to the Bricklin. This is an ambitious book of big ideas.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

After a slightly overlong prologue and introduction, Dream Car accelerates to a thrilling speed. The car lore is strong here. Anastakis, a professor of business history, understands the broad cultural currents that shaped the car-manufacturing sector and gave rise to the Bricklin. This is an ambitious book of big ideas.

The crisply argued central premise is that the Bricklin failed but was not quite a failure. Malcolm Bricklin built almost three thousand cars in New Brunswick, the first time since the 1940s that any manufacturer other than the Big Three had achieved that on this continent, “thus forever carving his name into American auto industry lore.”

This moment occurred, Anastakis argues, as the golden age of bold, archetypal inventors who sold North Americans the freedom of mobility was ending. It was the dawn of a new era marked by cold, bottom-line profiteering, reliance on government subsidies and bailouts, and concerns about the safety and environmental impact of the automobile.

There were, of course, inherent contradictions. Hatfield wanted well-paying manufacturing jobs; Bricklin sought low-cost labour. To launch his company, Bricklin played the role of a swashbuckling, innovative cowboy; but to make it succeed he needed to be a conventional, straitlaced, by-the-numbers manager. That eluded him, and it continued to elude him for decades after as he leapt from one faddish venture to another.

Advertisement

Still, as Anastakis shows in a chapter titled “Demise (Rebirth),” the Bricklin moment was unforgettable. The name became synonymous with failed government job-creation schemes, but today hundreds of Bricklin owners lovingly maintain their cars. Last fall, dozens of them from around the world gathered in Saint John, New Brunswick, to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the car and to tour the one-time manufacturing plant where it was built.

Bricklin himself continues to explore new opportunities and has met with the man to whom he was a “spiritual precursor,” Tesla CEO Elon Musk. As for Hatfield, Anastakis traces his scandal-ridden political demise; but, unfortunately, he barely nods at the late premier’s own grudging rehabilitation in New Brunswick — now that history has come to focus more on his continuation of major social reforms, his support for official bilingualism, and his moderate Tory government.

The final reckoning for the Bricklin saga is that, five decades later, it provides rich raw material for an astute and able historian like Anastakis. New Brunswick lost $23 million in the deal, and the province wasn’t modernized in the way its flamboyant premier had hoped. But, by the metrics of myth and cool, it got back far more than it invested — and it got a great story. Hatfield surely would consider that a success.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Save as much as 52% off the cover price! 6 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital.