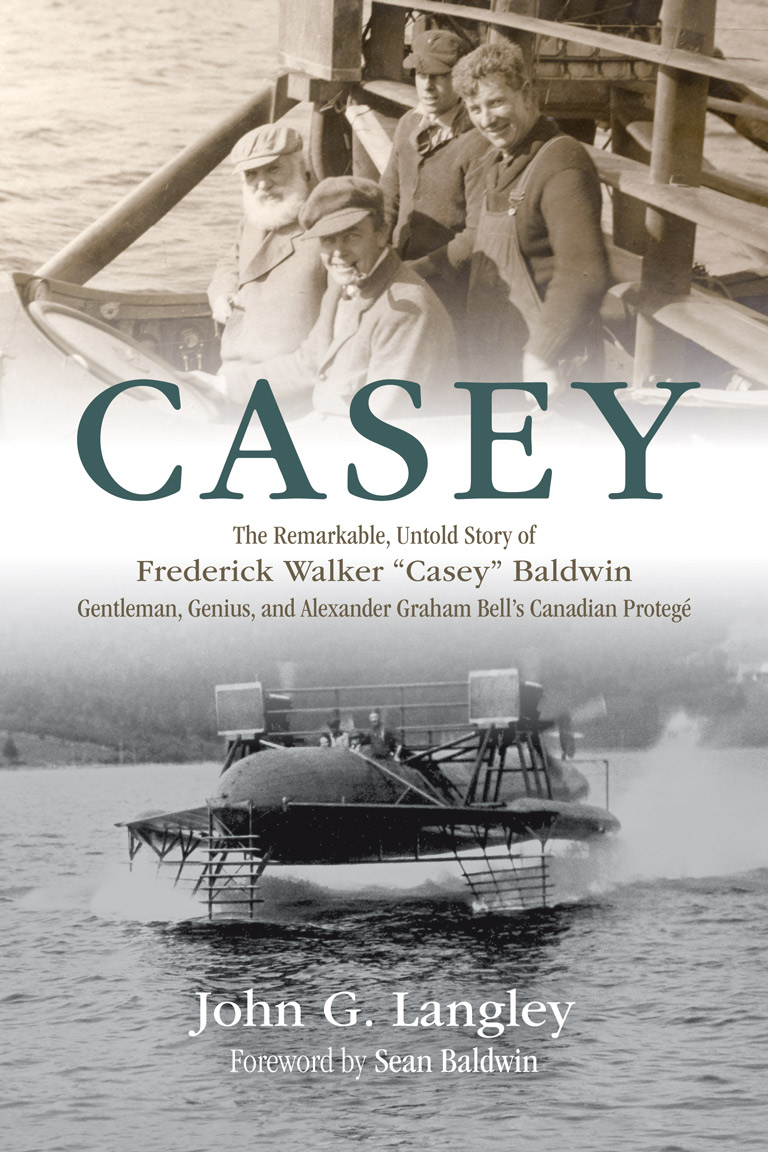

Casey

Casey: The Remarkable Untold Story of Frederick Walker “Casey” Baldwin: Gentleman, Genius, and Alexander Graham Bell’s Canadian Protegé

by John G. Langley

Nimbus Publishing,

312 pages. $24.95

The story of Alexander Graham Bell’s bold aerial experiments at Baddeck on Nova Scotia’s Cape Breton Island — tests of massive kites that culminated in the 1909 flight of the Silver Dart, the first powered craft flown in the British Empire — has been told in countless books. The pilot for that record-setting flight, local boy J.A.D. McCurdy, became a household name, at least in Nova Scotia. But he was not the first Canadian to fly; that distinction was earned by another young man in Bell’s orbit, Frederick Walker Baldwin.

Casey Baldwin, as he was known, was a Toronto-born, university-trained mechanical engineer who played a key role in Bell’s experiments and became a beloved member of the inventor’s inner circle. When Bell’s cigar-shaped, water-skimming hydrofoil, the HD-4, set a world speed record for a water-borne craft on Nova Scotia’s Bras d’Or Lakes in 1919 — topping seventy miles (112 kilometres) per hour — Baldwin was at the controls.

Nova Scotia author John G. Langley gives Baldwin his due in this biography of “a great, unheralded figure in Canadian history,” as Langley puts it, whose life and accomplishments have languished in the long shadows cast by Bell and McCurdy. Langley followed previous researchers through the vast archives at the Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site in Baddeck, where he lives. But access to unpublished private correspondence still in the Baldwin family’s hands offered fresh insights into his subject.

Baldwin came to Cape Breton with an impressive pedigree: His grandfather Robert was the reform politician who forged the Baldwin-LaFontaine alliance that brought responsible government to the Province of Canada in 1848. A star athlete in his university days — the poem “Casey at the Bat” was the inspiration for his nickname — Baldwin was enthralled with the Wright brothers’ test flights and designed a flying machine of his own, despite an engineering instructor’s admonition to stop “wasting class time on such foolishness.” His life changed in 1906 when McCurdy, one of his University of Toronto classmates, recruited him to help with Bell’s experiments.

The aging inventor and his twenty-four-year-old protegé hit it off, working closely on kite construction and the boat designs that culminated in the HD-4. Bell considered Baldwin “quite a genius,” and Mabel Bell was delighted to see her husband “working in company with a capable young man who so thoroughly believes in him.” A founding member of the couple’s Aerial Experiment Association, Baldwin became the first Canadian (and first British subject) to fly a heavier-than-air machine in 1908 — beating McCurdy by a year — when he kept a prototype in the air for a distance of three hundred feet (ninety- one metres) in upstate New York. Baldwin also devised the aileron, a horizontal control rudder essential for flight.

Langley, a retired lawyer who has written a biography of Halifax steamship-line founder Samuel Cunard, deftly traces Baldwin’s transition from aviation industry pioneer (he established a factory that briefly produced planes at Baddeck) to his work on Bell’s innovative hydrofoils. When the inventor died in 1922, his last wish was that his family “stand by Casey” and continue to fund his efforts to perfect the hydrofoil. In the 1930s Baldwin followed his illustrious grandfather’s lead and went into politics. Elected to the provincial legislature, he promoted Nova Scotia’s nascent tourism industry and was instrumental in the creation of Cape Breton Highlands National Park, which opened in 1941.

Casey is a well-researched biography of a man eulogized upon his death in 1948 as “a legendary figure” and “one of Nova Scotia’s most distinguished adopted sons.” Thanks to Langley, he now has the acclaim he deserves.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement