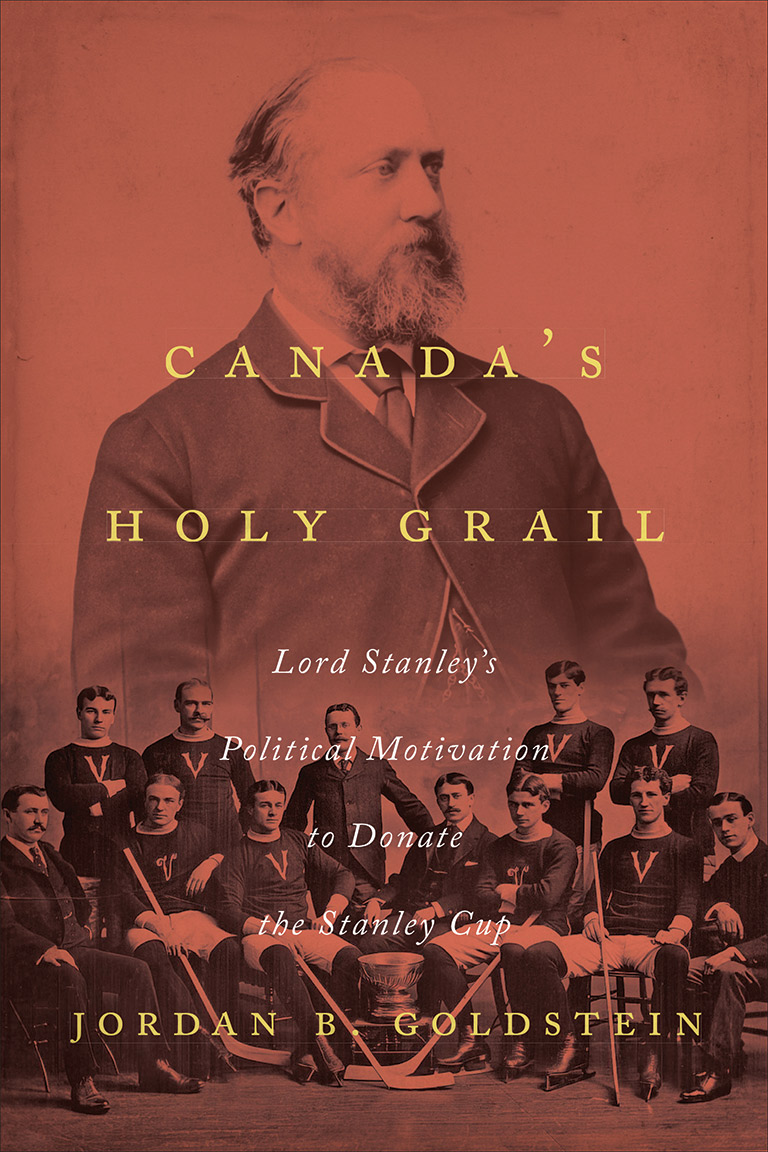

Canada’s Holy Grail

Canada’s Holy Grail: Lord Stanley’s Political Motivation to Donate the Stanley Cup

by Jordan B. Goldstein

University of Toronto Press

341 pages, $32.95

For a hockey-crazy country, it makes sense that hockey’s ultimate award — the Stanley Cup — holds a prominent place in the Canadian psyche. The cup is a Canadian icon, but how did a silver trophy donated by a Governor General in 1892 become a meaningful part of our identity?

According to Jordan B. Goldstein, author of Canada’s Holy Grail: Lord Stanley’s Political Motivation to Donate the Stanley Cup, it was by design. When Lord Frederick Arthur Stanley, Canada’s sixth Governor General, donated the Dominion Hockey Challenge Cup (later known as the Stanley Cup) in March 1892, he set out to foster Canadian unity and nationalism.

“Donating the cup was an attempt on [Stanley’s] part to build a nation through sport. Given that as governor general, he was head of the Canadian state, his act was political. Setting aside that he had a personal interest in ice hockey and desired to promote it, the creation of the Stanley Cup had political implications,” writes Goldstein, a professor in the Department of Kinesiology at Wilfrid Laurier University.

When Stanley served as Governor General from 1888 to 1893, Canada faced two potential outcomes: grow as an independent nation and remain close to Great Britain, or join the United States. He also recognized the division between French and English Canada as well as the difficult and fractious nature of Canadian politics at the time.

While Stanley wanted to help Canada mature, he understood that his role required impartiality, so he approached the task of building unity — an inherently political act — via his mandate of celebrating excellence.

Stanley chose to celebrate hockey. He envisioned a national championship and provided it with an award. “A physical symbol of national ice hockey supremacy would help support the Canadian state by inducing competition across a national system of ice hockey participants and thereby fostering a shared national sentiment,” writes Goldstein.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

In exploring Stanley’s motivation, Goldstein looks at Stanley’s life as it intersected with Canadian history, identity, philosophy, politics, and, of course, sports. He also explains why Stanley thought only hockey could be Canada’s national sport, and not baseball or lacrosse, both of which were popular at the time. Baseball belonged to the United States, while lacrosse — Canada’s national game at the time of Confederation — had lost its appeal as its supporters chose to remain true to the British Amateur Code rather than seeing lacrosse grow as a professional sport.

In short, to understand why Stanley donated the cup, we must also understand his time as Governor General and why, during a time of “national pessimism, especially in terms of national identity and culture,” Canada needed a strong symbol.

Even though Goldstein shares Stanley’s love of hockey, Canada’s Holy Grail is not a light read about the Governor General and his prize. Instead, it involves meticulous analysis that relies on primary and secondary sources. While historical analysis may not be everyone’s silver cup, Goldstein’s research is fascinating, and his book allows readers to understand a unique part of Canada’s history and identity. It also tells us how a trophy donated by a Governor General became an enduring symbol of the country.

As a result, Canada’s Holy Grail is well suited for anyone who loves hockey, Canadian history, and Canadian political thought — and who is not afraid of some intellectual work. In the end, we owe Stanley great thanks for creating a Canadian icon and, at the same time, helping to create a more unified Canada.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Our online store carries a variety of popular gifts for the history lover or Canadiana enthusiast in your life, including silk ties, dress socks, warm mitts and more!