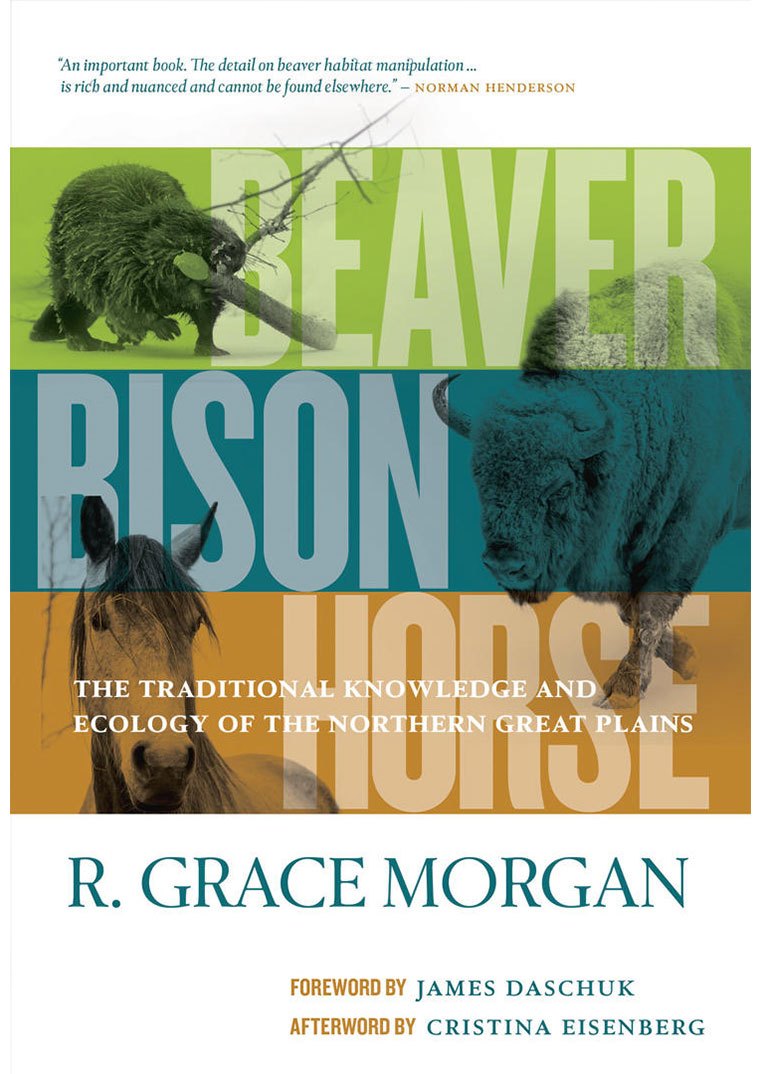

Beaver Bison Horse

Beaver Bison Horse: The Traditional Knowledge and Ecology of the Northern Great Plains

by R. Grace Morgan

University of Regina Press

352 pages, $34.95

One of the central arguments of R. Grace Morgan’s innovative new book is that, prior to trade with Europeans, Indigenous peoples of the prairie region did not hunt the beaver. They well understood the importance of this species to water management, specifically the role of beaver dams in creating water reservoirs that enabled both bison and Indigenous people to live on large tracts of North America that otherwise could not sustain their populations.

Previously studied in large-scale monographs by F.G. Roe and others, the bison and the horse are also part of Morgan’s history, entitled Beaver Bison Horse: The Traditional Knowledge and Ecology of the Northern Great Plains. But it is the beaver that receives star treatment for its little-known role in sustaining ecosystems that supported Indigenous people over many centuries.

Morgan’s book was an outgrowth of her earlier investigations into the ecological history of the Qu’Appelle River basin, which stretches across southeastern Saskatchewan from its source at Lake Diefenbaker to its confluence with the Assiniboine River in western Manitoba. For Beaver Bison Horse, the author expanded the scope of her research to infer that her thesis applied to the much larger great plains region; but she acknowledged that this inference awaits further empirical studies.

To address this history, Morgan applied three different forms of evidence — ecological, archaeological, and historical. The chapter on ecological evidence represents an outstanding analysis in its own right. This densely argued treatment displays Morgan’s in-depth knowledge of the ecology and natural processes of southern Saskatchewan and other prairie regions with similar characteristics.

She carefully studied grassland plant species to reveal the ways that bison most likely moved across the plains in search of diverse grasses as they cured in different seasons, reconstructing their movements from the growth cycles of the vegetation. The indispensable factor that enabled bison migrations was recurrent access to water — which was stored by beaver dams in reservoirs that ensured its supply, even in dry years and climatic eras.

The archaeological section also contains valuable insights. For example, Morgan applies archaeological analyses to Indigenous stone rings and their spatial distribution, and she combines them with other evidence to reconstruct the movements and seasonal patterns of Indigenous people as they sought bison across the region prior to contact. While the analysis sometimes relies on logic and inference rather than data, it represents a carefully reasoned attempt to compensate for the lack of hard evidence. Morgan’s imaginative approach enables a creditable historical reconstruction of precontact history by applying available archaeological tools to its study.

Morgan’s chapter on historical evidence represents a less successful effort to use secondary sources to test her theory regarding First Nations prohibitions on beaver hunting. The research in primary textual sources is slight, and the treatment of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is incomplete. Largely omitted is the role of another important Indigenous people — the Métis. Morgan references the Métis only in two brief discussions. Yet the Métis were engaged in hunting, processing, and trading bison products over much of the prairie and northern great plains regions, especially following the amalgamation of the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company in 1821.

Recent historical work by Brenda Macdougall and Nicole St-Onge has described the Métis practice of forming huge hunting brigades and establishing hivernants as bases of hunting operations across the west. Operating in different seasons, they staged especially large-scale hunts in the summer, overturning long-standing First Nations patterns of hunting in the fall and winter. The vast scale and spatial distribution of Métis hunting likely disrupted both bison movements and more localized First Nations hunting patterns; but the specific impacts are not treated here and await further investigation.

Beaver Bison Horse significantly expands our understanding of the interface between human and ecological histories of the prairie region. Given the subtitle’s reference to traditional knowledge, the lack of oral history research with First Nations Elders is disappointing. Nevertheless, Morgan’s book offers promising methodologies and ways of thinking about the history of Indigenous peoples as well as the animals that have played such influential roles in their histories.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement