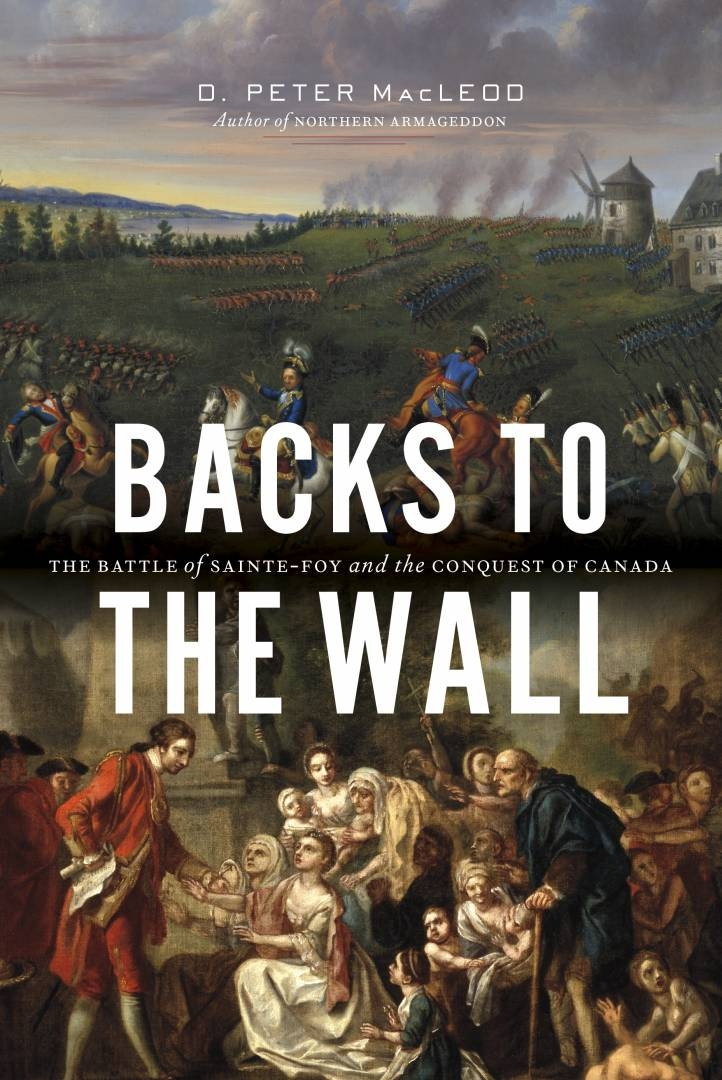

Backs to the Wall

Backs to the Wall: The Battle of Sainte-Foy and the Conquest of Canada

by D. Peter MacLeod

Douglas & McIntyre

271 pages, $34.95

Every student of Canadian history learns at one time or another that in September 1759 the British led by James Wolfe defeated the French under the command of Louis-Joseph de Montcalm at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. For all intents and purposes, Wolfe’s victory marked the end of the French empire in North America, which was confirmed four years later by the Treaty of Paris negotiated at the conclusion of the Seven Years War. These events and decisions had lasting consequences for the Frenchspeaking inhabitants of Quebec and their First Nations allies.

But history is rarely as neat and tidy as the textbooks might have it. While the French were indeed beaten in 1759 — “a day that I’d like to forget for the rest of my life,” remarked one French captain who had fought in the battle — the fight was in fact not quite done. French military leaders, including the clever and courageous Fran- çois-Gaston de Lévis, who replaced Montcalm, were confident that they could still drive the British out of Quebec. Indeed, in Lévis’s view, the so-called decisive battle of 1759 had not settled anything.

Creatively utilizing an array of primary source material, D. Peter MacLeod, the preConfederation historian at the Canadian War Museum, takes us back to the late fall of 1759 and the beginning of 1760 to carefully chronicle the French attempt to undo the British occupation. The fact that this military effort was ultimately not successful does not detract from the importance or suspense of the story MacLeod skilfully tells, or from the fact that painting history in broad strokes often misses significant details in determining how past events unfolded.

Central to MacLeod’s narrative are the events leading up to the Battle of SainteFoy, close to Quebec City, at the end of April 1760 — a battle the French won. In the months after the confrontation on the Plains of Abraham, the British, under the command of James Murray and headquartered at the Quebec garrison, were in rough shape. Without proper provisions of fruits and vegetables, more than 650 British soldiers succumbed to the ravages of scurvy. The British were weak and demoralized, but they still controlled the heavy guns mounted on the walls of Quebec and all the other artillery that once belonged to the French.

In the spring of 1760, Murray and Lévis, both dealing with an assortment of problems of manpower, weapons, and the absence of their respective navies, were locked in a dangerous game of chess. When the two men and their respective troops finally faced off at the Battle of Sainte-Foy on April 28, 1760, Lévis, assisted by French-Canadian militia and First Nations, came out on top.

The all-but-forgotten French victory, asserts MacLeod, was “a remarkable feat of arms, arguably the greatest single military achievement of the Seven Years War in North America.” Yet it was not enough. The French in North America, lacking naval support and receiving little help from France — which was fighting with the British and Prussians across Europe and Asia — could not retake the Quebec garrison and other occupied territory. British warships based in the Thirteen Colonies were able to reach Quebec in time and made all the difference. “We are,” wrote Lévis in late June, “no longer able to remain in the field, lacking provisions, munitions, and generally everything. It’s amazing that we manage to survive at all.” Quebec, and with it New France, was truly lost to the British for good.

History is full of what-ifs. Following the French success at Sainte-Foy, had Lévis and his men somehow attained a second victory at Quebec, who knows what would have transpired or how the terms of the Treaty of Paris might have been altered. This type of “alternative history” seems “absurd,” MacLeod concedes. From our perspective more than 250 years later, the events of 1759–60 are seemingly “engraved in stone.”

But up close, as MacLeod suggests, history is “considerably more fragile.” In 1760, he points out, “the future remained a world of unknown possibilities and opportunities, and Canadian militia, French soldiers, and the Seven Nations warriors expended a great deal of effort to shape what is to us our fixed and unchanging past.”

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement