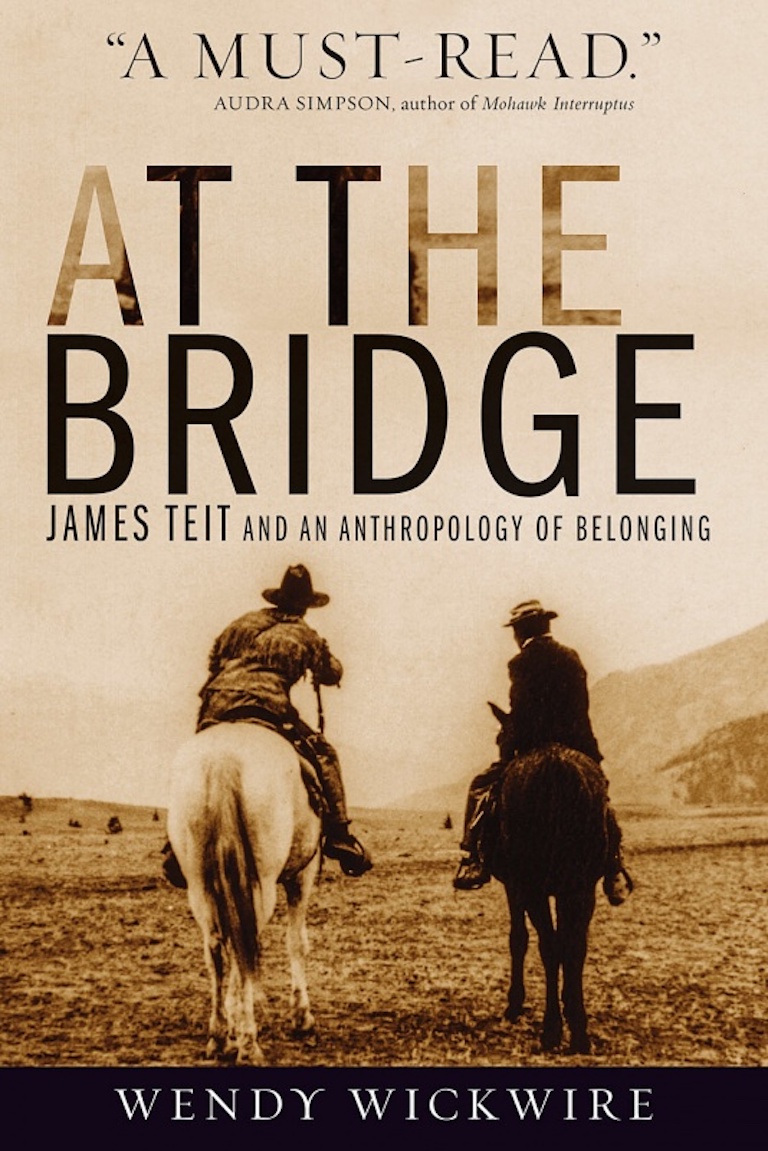

At the Bridge

At the Bridge: James Teit and an Anthropology of Belonging

by Wendy Wickwire

UBC Press,

400 pages, $34.95

“Only those few whites who help us ... uphold the honour of their race.” This statement was drafted by chiefs from the interior of British Columbia as part of a 1911 memorial to James Teit, who, as a “white agitator,” was one of their few friends. Both as a prolific ethnographer who lived among the people he studied and as an Indigenous-rights activist, Teit was a rarity in his time.

Teit was someone who made an appearance, made a difference, and then disappeared from the public record, according to University of Victoria historian Wendy Wickwire. In her book At the Bridge, Wickwire painstakingly unearths the life and legacy of someone who was undeservedly “invisibilized.”

How did this happen? Much of Teit’s work was done under the supervision of groundbreaking American anthropologist Franz Boas, who frequently published Teit’s field work without naming him. Teit also did valuable work for the Geological Survey of Canada, but references to him in the official record are few — probably because he ran afoul of the federal government for his activity on behalf of the Allied Indian Tribes of British Columbia. He also had no interest in self-promotion.

Wickwire first stumbled upon Teit’s legacy in 1977 while doing contract work to transcribe audio recordings of Syilx (Okanagan) songs. She discovered that Teit had recorded some two hundred songs on wax cylinders between 1912 and 1920, and she tracked down the recordings deep in the bowels of what is now the Canadian Museum of History, along with stacks of photos and handwritten field notes. “It was now clear that I was on the trail of a most remarkable ethnographer,” Wickwire said after immersing herself in Teit’s work.

James Alexander Tait was born in the rugged Shetland Islands of Scotland in 1864. He changed his name to Teit to honour the Scandinavian origins of the Shetlandic people. Since there were few opportunities for him in his homeland, he travelled to the British Columbia settlement of Spences Bridge at age nineteen to work for his uncle. He married a Nlaka’pamux woman named Antko and homesteaded on land adjacent to his wife’s village. Through Antko, he became part of Nlaka’pamux community life and attained fluency in three B.C.-interior languages.

In 1894, an encounter between Teit and Boas, who was just beginning to make his mark in the world of anthropology, changed the course of both men’s lives. Boas, a German-born, American-based scholar, had made several field trips to study the Northwest Indigenous peoples but found it difficult to get people to open up to him. He needed an “informant,” someone with good language skills and connections to the culture. Boas found that person in James Teit.

According to Wickwire, the arrangement gave Boas the data he needed to advance his theories of cultural difference, and it gave Teit the public platform and financial support to assist his Nlaka’pamux friends in their struggle against settler colonialism. Teit supplied Boas with data such as body measurements of Indigenous people and territorial maps as well as stories, songs, and artifacts. The latter included baskets and other articles, often made by women who were paid for their work.

The two anthropologists’ outlooks, however, were different. Boas, from his museum perch in distant New York City, sought to collect the remnants of what he viewed as a dying culture. The sooner the Indigenous peoples were assimilated, the better, he believed. Teit, immersed in the Nlaka’pamux community, saw that he was documenting a vibrant, living culture.

Wickwire attributes Teit’s sympathetic attitude towards Indigenous land rights to his Shetlandic background. In his time, many Shetlandic crofters were thrown off their lands and into abject poverty by greedy landlords. Teit saw the same thing happening in British Columbia as settlers encroached on Indigenous territory.

In an unusual move for his time, Teit superimposed a map of traditional Nlaka’pamux territory onto the official B.C. map and listed key Indigenous place names within that territory. Wickwire describes this as an “insurgent challenge to the imposition of new maps asserting the colonial presence.”

She does a thorough job of unearthing Teit’s legacy. Her book is filled with detail, anecdotes, and personal reflection. It’s an inspiring must-read for anyone interested in reconciliation today.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement