Arming and Disarming

Arming and Disarming: A History of Gun Control in Canada

by R. Blake Brown

The Osgoode Society

370 pages, $70

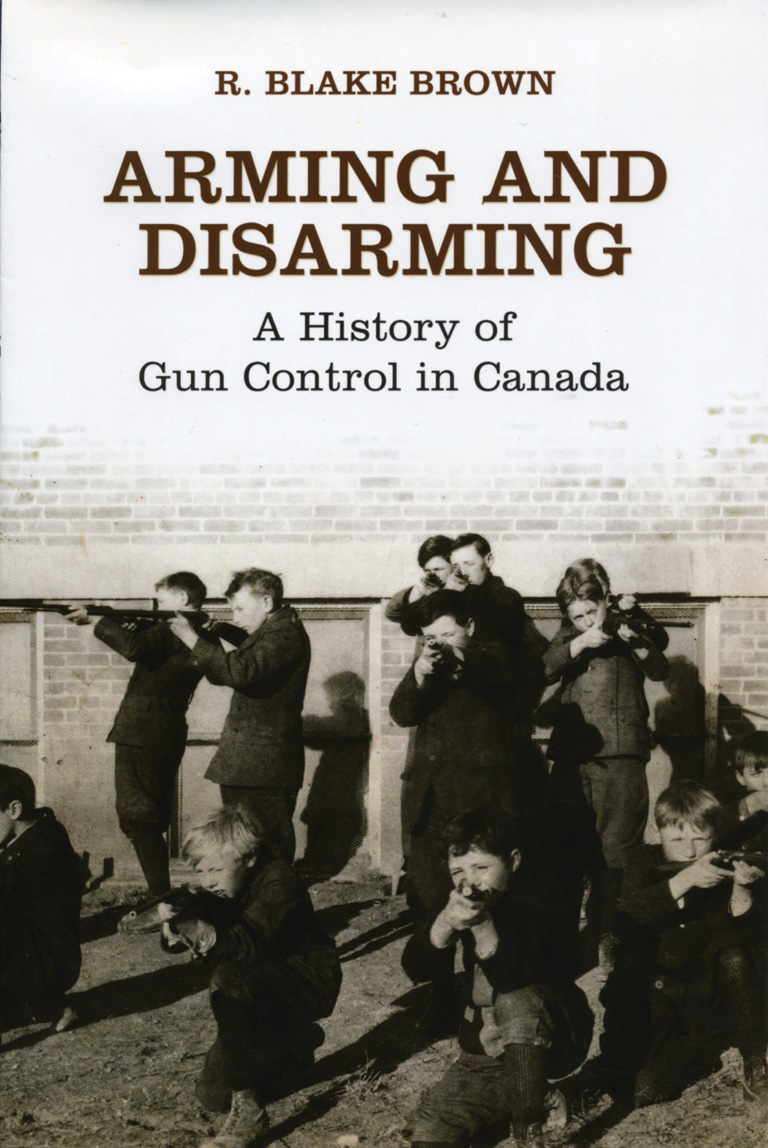

To modern eyes that have seen too many images of school shootings, the dust-jacket photograph on this book is disconcerting: Snapped in Saskatchewan just after the First World War, it shows a group of boys brandishing rifles.

In Arming and Disarming, Blake Brown undertakes a thorough review of the history of gun control in Canada and explodes the myth that we have never been as gunloving as our American neighbours. The prairie boys were not dangerous delinquents — Canadian lads under the age of sixteen could use rifles for hunting and target shooting without restriction well into the twentieth century.

Brown, who teaches history at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax, found that firearms were surprisingly scarce in pre-Confederation Canada. Militiamen mustered without guns or armed with outdated muskets, and gun violence was almost unknown. An incident in 1857 prompted the Toronto Globe to note that it was rarely called upon “to record man-shooting in Canada.”

That changed when the U.S. Civil War unleashed a flood of cheap, reliable firearms on both sides of the border. The threat of American invasion prompted the Canadian government to encourage rifle clubs and target shooting to ensure a body of trained marksmen was available if needed to defend the border. And, while Canada lacked a U.S.- style constitutional right to bear arms, John A. Macdonald and other political figures felt bound by the English Bill of Rights and its guarantee that His Majesty’s subjects could possess “Armes for their defence.”

But not everyone enjoyed this right. When gun-control measures were implemented, Brown shows, they left firearms in the hands of “trustworthy British men” while targeting ethnic groups considered potentially dangerous. Conquered Acadians and Canadiens in the 1750s, Aboriginals and immigrant labourers in the nineteenth century, and enemy aliens during the First World War bore the brunt of this double standard.

The distinction between handguns and long guns under Canadian law dates to the late 1800s, when access to cheap, easily concealed revolvers was blamed for a rise in shooting accidents, suicides, and crime. This “pistol fever,” as one newspaper termed it, led to a ban on carrying handguns and restrictions on their sale to young people.

As for rifles and shotguns, it is surprising to learn that Ottawa demanded the licensing and registration of all firearms — even those owned by trustworthy citizens — as a temporary measure during the Second World War. That move foreshadowed the controversial long-gun registry established in 1995 in response to the massacre of fourteen women at Montreal’s École Polytechnique in 1989. Brown takes the story into the present day and examines how ballooning costs undermined the public-safety rationale for gun control and enabled Stephen Harper’s government to dismantle the registry last year.

Arming and Disarming provides fascinating insights into Canada’s love-hate relationship with firearms. Macdonald, we learn, opposed an early gun-control measure in part because “lawless characters” from America “in the habit of carrying weapons” would be tempted to come north to prey on unarmed Canadians. And a Toronto gun dealer’s 1882 advertisement touting the Winchester repeating rifle’s ability to “kill sixteen Fenians in as many seconds without reloading” says something about prevailing attitudes toward Irish extremists.

One of the most intriguing nuggets is Brown’s discovery that the fledgling U.S. National Rifle Association turned to Canadian shooting clubs in the 1870s for inspiration and advice. Canadians “taught us practically our first rifle lessons,” a sportsmen’s magazine noted at the time, and Americans “owe her [Canada] a lasting debt of gratitude.” Given the gun violence and bitter gun-control debate gripping America today, Canadians can only wish we could turn back the clock.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement