A Stunning Backdrop

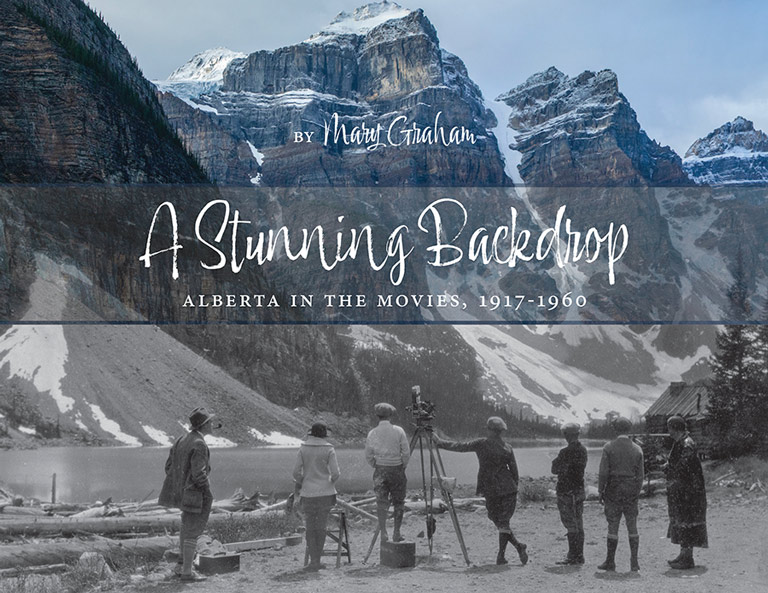

A Stunning Backdrop: Alberta in the Movies, 1917–1960

by Mary Graham

Bighorn Books

415 pages, $54.99

The title of this comprehensive book, which looks at more than four decades of moviemaking in Alberta, is partly ironic. As author Mary Graham makes clear, the peaks, plains, and rivers of Alberta are indeed stunning, but they are far more than a backdrop. Graham charts a complex back-andforth between Alberta’s landscapes, resources, film crews, and ordinary citizens, and the Hollywood productions that came in search of the province’s dramatic beauty.

Graham, a journalist and film historian, has done extensive research, digging deep into primary documents and archival photographs. She gives detailed summaries and behind-the-scenes stories of more than forty films shot in Alberta, while discussing how these American — and, occasionally, British — productions affected ranching communities, mountain towns, and the Indigenous peoples who lived in and around the southern Alberta foothills.

There is a great deal of raw information here. It can become repetitive, partly because the films themselves were often repetitive, especially in the early days of the so-called “Northwest melodramas,” which were almost always packed with menaced wilderness waifs, wrongly accused fugitives, sinister French-Canadian trappers, and upstanding Mounties (sometimes with “a curious tendency to burst into song”).

There’s a who’s who of Hollywood names, including directors Ernst Lubitsch, John Ford, and Otto Preminger and stars John Barrymore, Marilyn Monroe, Jimmy Stewart, and even the dog Lassie, who arrived in Banff “with a human entourage.” Graham recounts some funny anecdotes, whether it’s American actor Robert Mitchum getting around the puritanical liquor laws of 1950s Alberta, actress Shelley Winters showing up in Calgary in a three-quarter-length fur (in the middle of summer!), or filmmaker Billy Wilder finding Canadian conifers insufficiently green and having some shipped from California.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

There are also serious issues at stake. As Graham points out, Hollywood might have talked up the rugged “realism” of shooting in the Rockies, but many of the resulting films helped to manufacture a cinematic fantasy of Canada’s West as pure, remote, and unpeopled, playing into myths of “savagery” and settlement.

Graham discusses the overlap among the film industry, Canadian tourism, and the founding of the Calgary Stampede, a popular entertainment spectacle that likewise mixes up actual history and commodified dreams of the Wild West. And she raises the difficult question of why Alberta was often standing in as the American frontier, or the Austro- Hungarian Empire, or Nazi-occupied Norway, even as Canada struggled to develop its own film industry and tell its own stories.

Some of the book’s big ideas are raised but not fully followed up. Graham is most effective in fusing factual research with larger analysis in her account of the experiences of First Nations people working with the film industry, in particular the Stoney Nakoda. Through interviews with Elders who recall stories of Hollywood shoots, Graham shows that, far from being “simply part of the scenery necessary to the picture,” as one 1920s filmmaker dismissively remarked, Indigenous people were active participants on film sets, working as knowledgeable guides, skilled animal handlers, and cultural consultants.

As Graham writes, “Working in film provided desperately needed income, broke up the monotony of existence on the reserves, and, in many instances, allowed them to practise banned cultural rituals, such as the Potlatch or the Sundance.” This came at a cost, however. Indigenous people “learned well to represent themselves as ‘Show Indians’ to placate the unrealistic idealizations and expectations of the settlers,” Graham suggests.

A Stunning Backdrop needed closer editing. There are occasional typos, spelling errors (“free reign”), and awkwardly integrated quotations. But Graham’s research, backed up with extensive notes, an impressive bibliography, and hundreds of clearly identified photographs, will be an invaluable foundation for scholars while offering a good general-interest read for film buffs.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement