The Unsettled Past

A decade ago, the historians and exhibit planners on Parks Canada’s Yukon field team sought advice from Rae Mombourquette, a heritage researcher with Tlingit, Northern Tutchone, and Tagish roots — and some Acadian, too — who was working on projects for the Kwanlin Dün First Nation in Whitehorse. The Parks Canada team had a new interpretive plan in the works for the handsome paddlewheeler SS Klondike, once a workhorse of Yukon River shipping and transportation that was retired in 1955 and since 1967 has stood as a National Historic Site on the Whitehorse riverfront. They wanted Indigenous input. One of the park staff shared an idea with Mombourquette: Maybe the site should include a welcome sign in all eight languages of the Yukon First Nations.

Mombourquette had worked on questions of First Nations self-government and land title in Yukon; she knew the issues. She told me recently, “One of my first comments about that welcome sign was, ‘It’s assuming a lot that Yukon First Nations are welcoming.’” Parks Canada’s consultation was not having a promising start.

There’s a happy outcome to this SS Klondike story. But before we get to that, let’s acknowledge that it has a familiar ring. From the national parks system’s beginnings at Banff, Alberta, in 1885, the creation of “wilderness” areas often began with the driving out of Indigenous and other communities. In Whitehorse, Kwanlin Dün elders remember when the SS Klondike site was one of their fish-drying camps. As recently as the 1970s, Parks Canada evicted twelve hundred people, mostly Acadians, to create Kouchibouguac National Park in New Brunswick. I knew that practice personally: I went to work for Parks Canada at the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site in Nova Scotia in the early 1970s, and I saw the foundations of homes in the former west Louisbourg neighbourhood that had been expropriated and torched to create a magnificent isolation around the fortress.

Today, more than two thousand of Parks Canada’s familiar plaques present designated places, people, and events of historic significance around the country. Parks Canada administers close to two hundred National Historic Sites — from mighty Louisbourg and the preserved gold-rush landmarks of Dawson City to melancholy Batoche, Saskatchewan, and charming Green Gables, Prince Edward Island — that are visited by millions of Canadians and other tourists every year. Surveys have suggested that, for many Canadians, historic sites — along with museums — are the most important and most popular sources of Canadian history.

Yet to long-established Indigenous communities, local governments, and deeply rooted settlers, Parks Canada’s arrival to establish a national park or historic site has sometimes felt like an invasion by big government, and its historical exhibits have often failed to draw on the different communities who were part of that history. So Mombourquette was hardly the first to suspect that being consulted by Parks Canada might not be a positive experience.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Nature parks like Banff may be the icons of Parks Canada, but historic sites have their own deep roots. Parks Canada’s first venture in historic site operation began at Fort Anne at Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, in 1917. Two years later, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada (HSMB) was established. In the Canadian government’s history-and-heritage world, the HSMB stands at the top of the heap. HSMB board members — historians, heritage professionals, and cultural administrators appointed by the Crown, one per province and territory — receive and assess nominations from the public and ultimately recommend which persons, places, or events Canada will officially designate as being of national historic significance. Parks Canada is the civil service agency that advises on, and implements, broad policy decisions around national parks and historic sites.

“In the early years, it was basically a matter of celebration,” long-time HSMB chair Richard Alway said of the board’s original objectives: a celebration of great men and great things done by the settlers of Canada. Indeed, the board once debated whether the Halifax explosion of 1917 was too sad and horrific to be declared of national historic significance. But over time the board, and Parks Canada, moved to an approach “that includes all the complexities of history,” Alway said — commemoration, not celebration.

The approach of commemoration, not celebration, has worked well for Parks Canada. At its historic site on the Plains of Abraham battlefield, would it celebrate the British victors or the French defenders? At Batoche, would it be the embattled Métis or the Canadian militiamen? It’s better, surely, to present and commemorate the event than to take sides.

“Commemorations from the early years … were largely military, and constitutional, and political, or trade — your nationbuilding,” Alway said. As the system became larger, new sites continued to emphasize explorers, colonizers, and builders and managers of fur-trade posts, railroad lines, and steamships — like Whitehorse’s SS Klondike. Yet, gradually, “historic significance” expanded to include social history, women’s history, and the experience of cultural communities — and, most recently, respect for Indigenous perspectives. “What we have to do is make sure that complexity, the broad scope of history, is truly recognized in the program,” Alway said.

In 2000, a new historic sites plan committed Parks Canada to placing more emphasis on Indigenous history, which it acknowledged to be an “underdeveloped” aspect of its mandate. Between 2000 and 2015, designations related to Indigenous history increased by thirty-one per cent. Meanwhile, the agency began to co-operate with First Nations and to co-manage some parks and historic sites — an initiative that started when the southern part of the Haida Gwaii archipelago off the coast of British Columbia became Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve, National Marine Conservation Area Reserve, and Haida Heritage Site, co-managed with the Haida Nation. Still, in 2015, sites addressing Indigenous history remained only twelve per cent of all designated Parks Canada historic sites. And the tragedy of Indigenous children’s forced attendance at residential schools — often far from their families and under appalling conditions — remained without official commemoration.

Then in 2015 came the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Funded by the survivors of residential schools as part of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement with the federal government, the commission went beyond exposing the truth about residential schools. It initiated a search for “the basis for a new relationship” between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians “based on a commitment to mutual respect.” Virtually all aspects of Canadian society needed to be reconsidered, the commissioners declared, adding: “Reconciliation will take some time.”

Time’s guardians at the Historic Sites and Monuments Board and on the history-and-commemoration side of Parks Canada were not spared the commission’s blunt assessment of their lack of respect and attention to Indigenous history and Indigenous expertise. The commission’s Call to Action 79 declared that the federal government, in collaboration with school survivors, Indigenous organizations, and the arts community, should “develop a reconciliation framework for Canadian history and commemoration.” It called for “a national heritage strategy for commemorating residential school sites” and their history and legacy, and it urged the integration of Indigenous peoples’ history, heritage values, and memory practices into Canada’s national heritage and history.

Some of those ideas are contained in Bill C-23, the Historic Places of Canada Act, which is currently before Parliament. If passed, the law will require the HSMB to take into account Indigenous knowledge, community knowledge, and academic knowledge in reaching decisions and to appoint First Nations, Inuit, and Métis board members. (Already, individuals from the three communities have been confirmed as representatives of three of the provinces and territories — including Mombourquette, who fills Yukon’s seat.) However, Call to Action 79, like the majority of the TRC’s Calls to Action, remains unfulfilled pending passage of the legislative amendments. “History is always evolving, and changing, and shifting,” Alway observed. “What you want is a program that is responsive to that — in a measured way.”

Let’s get back to Rae Mombourquette and the SS Klondike in Whitehorse. After telling me of her own tart comment — that Parks Canada should not presume a welcome from First Nations — Mombourquette went on to say, “I said that in one of the first meetings. And people were like, ‘Absolutely! We’re not going to have that. We definitely want something more meaningful.’ And that’s what we got. We made it such an inclusive and meaningful Indigenous-led and partnered project.”

Karen Routledge, a British Columbian who had recently obtained her doctorate in history, had just joined Parks Canada as the SS Klondike reinterpretation project began. She recalled how the first tentative encounters turned into genuine consultations with Elders and heritage workers from Kwanlin Dün, Ta’an Kwäch’än, Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in, and other First Nations of the Yukon River. They made the case that Yukon riverboats, previously seen mostly as pioneer technology, were also Indigenous history. Indigenous people worked on the boats, travelled on the boats, and shipped their trade goods and supplies in and out on them. Elders also spoke of the boats taking children to the residential school in Whitehorse and of the homes and fishing camps they once had on the flats where the SS Klondike National Historic Site now stands. For Routledge, attention to Indigenous knowledge opened up a fuller view of what the steamship should represent. “They spoke about how the exhibit should really have the river at its centre. It really did shape how we created that exhibit,” Routledge said.

“When you see historic images of First Nations people, often [the caption] will just say ‘unidentified, unidentified.’ So we worked with First Nations to source photographs where we could name the people. Anne-Marie Miller of Ta’an Kwach’an spent a lot of time calling around trying to identify people in one photograph in particular, a large family group. And so, when you go about the exhibit, most of the photos have people identified in them. With this exhibit, I really want visitors to come and recognize that they’re in Indigenous homelands and how integral Indigenous people were to the running of these boats. But I also really want Yukon First Nations people to come and feel welcome and at home there, and I think having people identified in the images ended up being a big part of that.”

Looking back, Mombourquette said, “I’m very proud of the way the exhibit turned out. We really changed the project.” Already, other opportunities for Parks Canada to co-operate on Indigenous and Yukon heritage matters have arisen from it. Routledge is sure that Indigenous partnership has meant that the SS Klondike now expresses a bigger, broader, more ambitious vision of Yukon history. And today there is a multilingual welcome sign in English, French, and eight Indigenous languages.

Parks Canada’s historic plaques are one program affected by the complexities of history and the commitment to commemoration, not celebration. Plaques were among Parks Canada’s earliest ventures into historical commemoration, and the traditional bronze tablets on stone cairns are iconic Canadiana; there are more than two thousand of them across the country. To convey what or whom is commemorated in only 642 characters (not words — every letter and space is a character) is no small challenge, and many plaque texts have given little space to Indigenous perspectives.

Parks Canada — in consultation with external experts and stakeholders, and sometimes prompted by public requests or controversies — has identified more than two hundred designations and their associated plaque texts for review and possible revision. This includes some that have honoured prominent statesmen or dedicated missionaries without mention of their roles in the residential school system. On its website, Parks Canada notes: “Some designations and their commemorative plaques include dated or insensitive content that does not reflect what is known or important to say about the country’s history today.”

A Parks Canada analysis of the plaques in 2019–20 found four main types of concerns with the designations and their corresponding plaque texts: “outdated or offensive” terminology; “absence of a significant layer of history,” usually Indigenous; “colonial assumptions,” meaning designations of colonial figures and nation-building events “from an overly European perspective”; and designations of persons whose views, actions, and activities are controversial or “condemned by today’s society.”

The review, which includes the opportunity for public comment, covers many well-known people, places, and events. The plaque honouring Canada’s first prime minister, John A. Macdonald, is being reviewed for colonial assumptions and absence of a significant layer of history. So are those of French explorer Jacques Cartier, founder of Quebec Samuel de Champlain, Mi’kmaw Grand Chief Membertou (or Anli-Maopeltoog), founder of Ontario’s public school system Rev. Egerton Ryerson, Cree-Assiniboine Chief Payepot (or Piapot), and Arctic explorer Martin Frobisher, among others.

Plaques commemorating forts, battles, treaties, explorations, and religious orders across the country are being reviewed for colonial assumptions, the absence of significant layers of history, and/or outdated or offensive terminology, as are commemorations of several national historic events, including the creation of the North West Mounted Police, the creation of the provinces of Manitoba and British Columbia, and the “discovery” of Prince Edward Island.

Inventor Alexander Graham Bell’s designation is being reviewed for controversial beliefs and behaviours, as are those of groundbreaking feminists Emily Murphy, Irene Parlby, and Nellie McClung. But critics point out that not everyone with potentially controversial beliefs is being scrutinized: Mohawk leader Thayendanegea, or Joseph Brant, whose plaque text fails to mention that he held people in slavery, is not currently under review. Nor is Quebec politician and newspaper editor Henri Bourassa, who opposed voting rights for women.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Bill Waiser, a widely published prairie historian and, until recently, Saskatchewan’s representative on the HSMB, offers Cumberland House, a fur-trading post in east-central Saskatchewan that was designated a National Historic Site in 1924, as an example of why plaque texts need review. The plaque there states: “For a century after its founding in 1670 the Hudson’s Bay Company was content to draw Indians down to the Bay to trade; but in 1774, after Canadian ‘pedlars’ on the Saskatchewan had begun to intercept this trade, Samuel Hearne was sent from York Factory to establish Cumberland House, the first of the Company’s great inland posts. Under Hearne, Matthew Cocking and William Tomison, this became the nerve centre for competition with the North West Company until the union of the two companies in 1821. Thereafter it remained an important trading establishment for many years.”

This text misunderstands who really brought Cumberland House into being: the Cree traders and trappers. “That was decided because of First Nations geography,” said Waiser. “They told Hearne where to put the post. It wasn’t Hearne who did it — and that needs to be reflected in the story of Cumberland House.”

This review of plaque texts has sparked controversy. In 2022 Larry Ostola, former vice-president of heritage conservation and commemoration at Parks Canada, who is now retired, raised the alarm in the National Post about “a new woke perspective” being imposed on the history of Canada. Ostola wrote that he had no problem with changing texts to remove offensive or outdated language, or to add an absent layer of history. However, he criticized the review of “controversial” views, asking: “Who gets to decide on the definition of today’s standards?” And he questioned why “colonial assumptions” and an “overly European perspective” are specifically called out in the review, arguing that the addition of an “absent layer of history” would be a sufficient remedy in these cases.

He also raised a concern about a provision in the proposed Historic Places of Canada Act that would permit the federal minister responsible for Parks Canada to revoke a designation of national historic significance, albeit only on the recommendation of the HSMB and only if the minister is of the opinion that the place, person, or event is no longer “of national historic significance or national interest.” Although Parks Canada’s 2019 Framework for History and Commemoration states that such a recommendation would only be made “in exceptional circumstances,”

Ostola argued that “we already live in a time of ‘extraordinary circumstances’ ... [when] Macdonald’s name and visage is being steadily obliterated throughout the country — a country that he almost singlehandedly willed into existence.” Ostola charged that political pressure was pushing Parks Canada to eliminate giants of Canadian history from its plaques and from public view. “Rather than adding further to our history, it appears Ottawa may be planning to subtract from it,” he wrote.

When I spoke with Ostola late in 2023, he described his critique as “a bit of a warning — and it doesn’t apply only to Parks Canada.” Noting the toppling of statues and the “cancelling” of historic figures, he expressed his hope that Parks Canada would “approach the past with humility, and with some degree of tolerance and understanding.” As his article says: “Where [national heroes] diverge from modern standards — or even from the standards of their day — it is appropriate to point that out. But that should not deny their other monumental achievements.”

Asked about the controversy, former HSMB member Waiser responded: “I never thought of removing anybody that’s been recognized. We are adding to the story, making it fuller. History doesn’t stand still.”

Alexandra Mosquin, principal historian at Parks Canada’s history and commemoration unit, was deeply involved in developing the 2019 Framework for History and Commemoration that now guides the agency’s work. Drawing on recent scholarship about historical thinking and best practices for public history, the framework explores fundamental principles of how Parks Canada should fulfill its mandate of “meaningful engagement” with Indigenous history, and with the needs of all its millions of visitors. For Mosquin, Parks Canada’s intention is not to subtract from history but to provide opportunities for people whose perspectives were previously ignored — particularly Indigenous people — to share and communicate their history on their terms.

Revisions to exhibits and plaques are “nothing new,” said Mosquin. “This is the work of historians: to ask questions in their own time, build upon the work of historians who came before them, and rethink to address the current interests of our time,” she said. Parks Canada has routinely revised wordings, particularly as other languages have been added or when faded or damaged plaques or cairns were refurbished. But a visit I made to Bellevue House in the spring of 2024 made it clear that the scale of the reconciliation-driven review is indeed new.

Bellevue House, set in a leafy neighbourhood in Kingston, Ontario, has a comfortable mid-Victorian English-Canadian homeyness; but when Parks Canada reopened it in the spring of 2024 after a lengthy renovation, a five-language multilingual sign stood at its entrance. The site now announces a “two-voice” presentation of the home of future Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, its famous tenant of 1848–49, when he was just beginning his career in law and politics. The new displays pay abundant tribute to Macdonald as “a nation-builder whose energy and political skills were essential to the success of Confederation.” But the house also presents that second voice: the one raised in criticism of Macdonald and his governments for the forcible assimilation of Indigenous nations through the Indian Act and residential schools, the one the truth and reconciliation commission calls on Canada to recognize.

These new Bellevue House exhibits quickly became controversial. Toronto Metropolitan University professor Patrice Dutil, a noted Macdonald scholar, denounced the presentation as a “fiasco” and a “national flagellation” designed “to demonize Canada’s past.” Dutil urged a boycott of Bellevue House, and he blamed the whole thing on the current prime minister. (Although, if Justin Trudeau must accept personal responsibility for all that is done during his tenure, why should John A. Macdonald not be held to the same standard?)

It’s true that Bellevue House is no longer what anthropologists call “a lineage shrine,” a place to worship our political ancestors. Like stately homes around the world, it now presents an “upstairs/downstairs” story, one attentive to the servant in the house as well as the master. Indeed, it skilfully opens visitors’ eyes to a global upstairs/downstairs, showing Macdonald’s Kingston in the 1840s as no backwoods outpost but one that the British Empire furnished with tea and cotton from Asia and sugar from the Caribbean, and where the First Nations of British North America had been very nearly removed from consideration.

A reconciliation take on a historic site is still a new thing in Canada, perhaps even something shocking. There may be places in Bellevue House where the messaging is heavyhanded. But Macdonald (and other Canadians) have ceased to be uncontroversial heroes whom we all admire. The Canadian public knows that and would be bored by, and skeptical of, a Parks Canada presentation that glossed over the controversies. What would drive Canadians away today is official history that pretended its audiences have never heard of things like residential schools or the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Advertisement

Similar issues came quickly to the fore when I talked to Anne Marie Lane Jonah, a Parks Canada historian in Halifax who was part of a small team responsible for the exhibit Fortress Halifax that opened at the Halifax Citadel in 2022.

A dominant presence in the heart of Halifax and a National Historic Site since 1952, the citadel has long — and quite appropriately — presented a military story: of the defence of Halifax and the British redcoats in garrison there.

With the truth and reconciliation report and Parks Canada’s reconciliation commitments in mind, Lane Jonah realized, “This changes everything!” She told me that there is a British story of Halifax and its location on the Chebucto peninsula — visible in fortifications all around the city — but there is also a Mi’kmaw story of Kjipuktuk and a French and Acadian story of Chebouctou. “They are all in the same space, and nobody’s story has to override anyone else’s,” said Lane Jonah. The Parks Canada team began to work with a new vision of Halifax as a place of power over centuries, where contending forces fought for empire and autonomy.

“Multiple perspectives multiplies work,” became Lane Jonah’s mantra, as the Parks Canada team — stripped down by budget cuts in 2012 — struggled with a much-expanded vision of the citadel. “Sometimes it was overwhelming — the amount that had to be done, and the various desires.” There were consultations with the citadel’s interpretation team, the Army Museum at the Citadel, the Nova Scotia Women’s History Society, the Medical History Society of Nova Scotia, the Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia, the Fédération acadienne de la Nouvelle- Écosse, universities, and scholars. Digital designers broke new ground in ways to overlap multiple perspectives on a single landscape. But, in Lane Jonah’s eyes, artist and mural painter Leonard Paul and the Mi’kmawey Debert Cultural Centre of Debert, Nova Scotia, were particularly important in illuminating how the citadel remains “an extremely painful colonial assertion, very violent” in Mi’kmaw history. “The pleasure of seeing those murals of Kjipuktuk and Mi’kmaw words on the walls, hearing Mi’kmaw voices, just really giving a sense of how large and complex that story is....” She let the rest of the sentence hang. Lane Jonah admits that it was an emotional moment when the new exhibit entitled Fortress Halifax got the approval of the project’s Indigenous cultural advisory councils — and later as word of mouth began to draw new and diverse visitors to the citadel. “This is emotional labour,” she said. “You are trying so hard to get it right.

“We joke,” she went on, “remember back when people thought history was boring and we were going to have to work really hard to engage them? That’s not the problem now.” Audiences today know that unresolved conflicts remain at the heart of Canadian history. The exhibit that would bore them is one that celebrated only power, progress, and success. Lane Jonah was willing to endure stress and strain to supersede that.

Are Parks Canada’s historic sites projects on the right track? Fifteen years ago, in response to a debate over the alleged killing of Canadian history through political correctness, the great Canadian historian Ramsay Cook preferred to celebrate “the broadening of Canadian history.” That broadening, he said, came from exploration of the “unlimited identities” of Canadians and through the endless negotiations among differing perspectives that typify Canadian politics and Canadian history. The Parks Canada mantra of commemoration, not celebration was not Cook’s phrase. But he would have known what it signified.

In Canada today, perhaps no agency has more potential than Parks Canada for bringing that broad, non-exclusionary vision of history to Canadians and visitors to Canada. Its hundreds of sites and thousands of plaques and designations reach every part of the country and are backed with vast resources of online text, photography, and video that are available at anyone’s fingertips. Its historians, archaeologists, exhibit designers, historical interpreters, and site guides form a team unlike any other in Canada, working nationally from a shared framework rooted in inclusion, relevance, and outreach. When the members of the TRC wrote that reconciliation will take some time, they did not say it would be painless.

“What Parks Canada offers in terms of a resource for understanding Canadian history, it has changed so much in the last ten years. It’s amazing,” Lane Jonah reflected. “People have risen to the challenge, and it has gotten so much richer. It’s exciting to be part of.”

Advertisement

Commemorating Residential Schools

In 2019, acting on a nomination received from the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR), the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada designated the residential school system as an event of national historic significance. In 2020 and 2021, in partnership with local First Nations and networks of survivors, it designated four former residential school sites — Shubenacadie in Nova Scotia, Shingwauk in Ontario, Portage la Prairie in Manitoba, and Muscowequan in Saskatchewan — as National Historic Sites, intended to become places of remembrance and healing.

Jennifer Wood, a residential school survivor who is the national centre’s intergovernmental liaison, said Parks Canada “has been a very willing partner in this process, and we have had a really good relationship.” She is particularly proud of a program called the Na-miquai- ni-mak (I remember them) Community Support Fund. The fund enables Indigenous youth and elders to plan their own community memorials to the legacy of residential schools. The NCTR has already approved 193 applications from across Canada. “We’re igniting embers and fires within the youth spirit,” she said.

When a community puts on its own event for healing, she has noticed, the nearest town will become involved as well. “People are taking down their walls and barriers and perceptions. So to me, that’s reconciliation.” — Christopher Moore

Plaque Flak

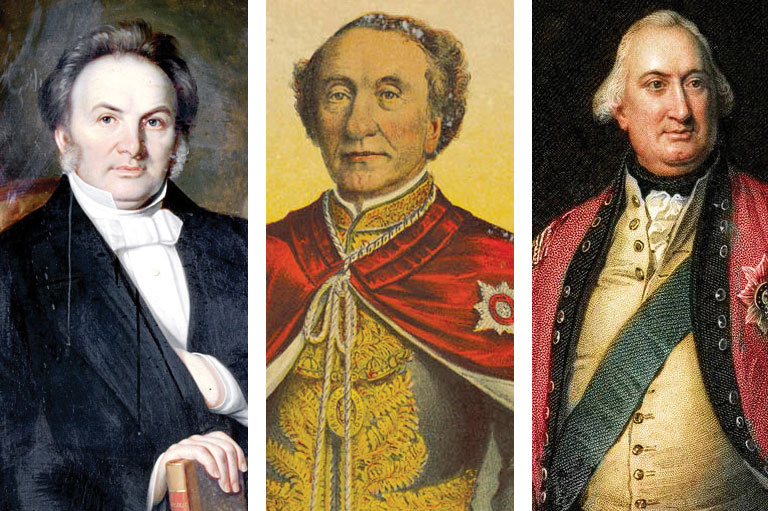

Parks Canada is reviewing the designations and plaques of dozens of national historic persons. Here are three:

Membertou (Anli-Maopeltoog)

Existing plaque text: The headman or Grand Chief of a large band of Micmac Indians living along the south shore of the Bay of Fundy, Membertou was also a great warrior and renowned shaman. When the French arrived in the early 1600s, he converted to Christianity and on June 24, 1610 became the first native chieftain to be baptized in what is now Canada. He helped the French establish a settlement in this area and traded furs with them for European goods. Membertou died on September 18, 1611, but the Micmac-French alliance which he began lasted for more than a century.

Year of designation: 1981

Plaque location: Port-Royal National Historic Site of Canada in Nova Scotia

Being reviewed for: Colonial assumptions, outdated or offensive terminology

Emily Murphy

Existing plaque text: Born in Cookstown, Ontario, Emily Murphy moved to the Swan River district of Manitoba in 1904 and about three years later to Edmonton. A fighter for women’s rights she became, as judge of the Edmonton Juvenile Court, the first female magistrate in the British Commonwealth. She led the five Alberta women through whose efforts women were legally recognized as “persons” and hence made eligible for admission to the Senate. Among the books she wrote under the pen name “Janey Canuck” were Seeds of Pine, sketches of life in Alberta, and The Black Candle, a study of narcotics and drug addiction. She died in Edmonton.

Year of designation: 1958

Plaque location: 11904 Emily Murphy Park Road NW, Edmonton

Being reviewed for: Controversial beliefs and behaviours

John Alexander Macdonald

Existing plaque text: Born in Scotland, the young Macdonald returned frequently during his formative years to his parents’ home here on the Bay of Quinte. His superb skills kept him at the centre of public life for fifty years. The political genius of Confederation, he became Canada’s first prime minister in 1867, held that office for nineteen years (1867–73 and 1878–91), and presided over the expansion of Canada to its present boundaries excluding Newfoundland. His National Policy and the building of the CPR were equally indicative of his determination to resist the northsouth pull of geography and to create and preserve a strong country politically free and commercially autonomous.

Year of designation: 1939

Plaque location: Formerly at Hay Bay, Ontario; removed in 2021

Being reviewed for: Colonial assumptions, absence of a significant layer of history

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement