Pulp Secrets Exposed!

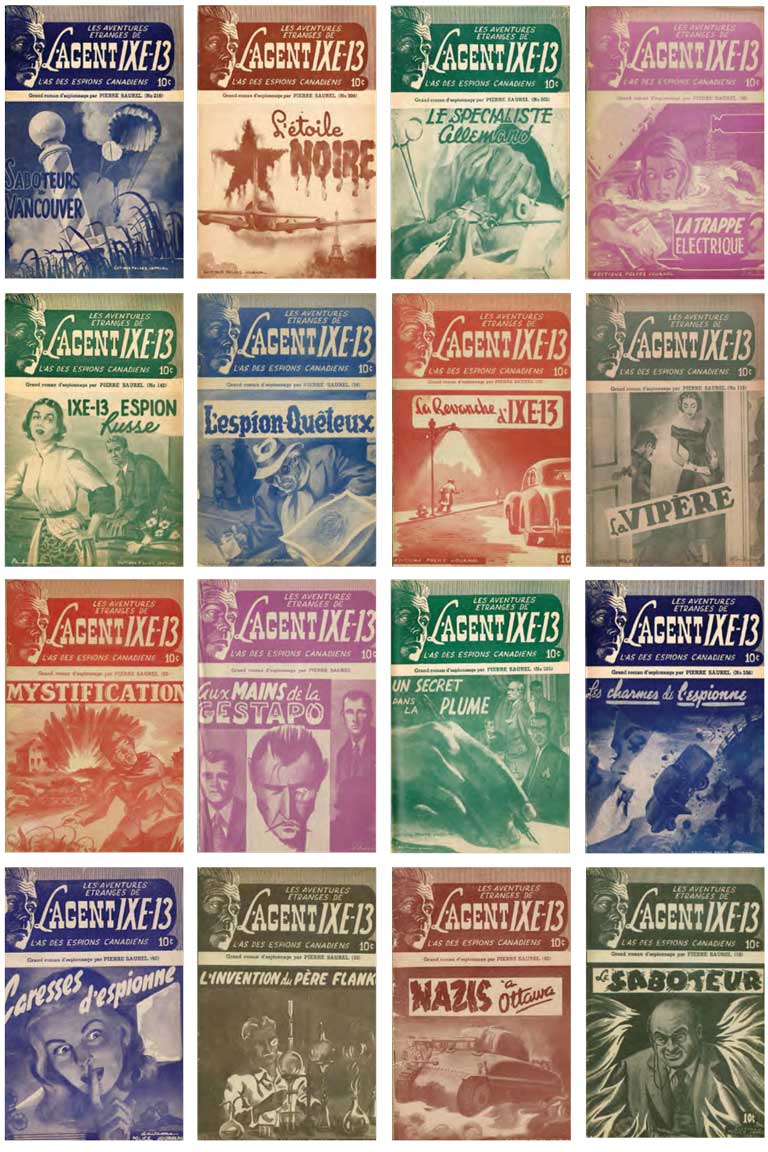

As the Allies closed in on Berlin, the intrepid French-Canadian spy Jean Thibault — known by the code name Agent IXE-13 — and his loyal lieutenant, Marius, were carrying out their mission to infiltrate the deepest lair of Nazi power. Disguised as German officers, the undercover agents had secured lodgings in Adolf Hitler’s headquarters. Now the two friends were alone, mere steps from the Führer’s private flat. They’d each been left with a machine gun, along with ammunition, two rifles, and their pistols:

“Mother of God,” Marius said, “we’ve never been so well treated.”

IXE-13 looked at the assembled weapons.

“All the better for us, Marius, we’ll be able to give the Allies a hand when the time comes. We still need to find a way to get to the Führer.”

But two resolute soldiers were standing guard at the door to the apartment of Germany’s madman.

It was going to be nearly impossible.

“Marius, the final assault is due any moment now, so when it happens, we’ll kill the two guards and rush together inside the Führer’s room.”

“Let’s do it, boss. But if you ask me, he’s surely asylum fodder by now.”

“Don’t worry about it, Marius. He was crazy from the get-go.”

Unfortunately, Agent IXE-13 and Marius didn’t manage to assassinate Hitler in that episode of Les Aventures étranges de l’Agent IXE-13 (The strange adventures of Agent IXE- 13), titled “Sus à Hitler” (Death to Hitler). But our heroes did escape from the Führer’s lair and lived on to fight Nazis in many more episodes to come. For IXE-13 and Marius were stars of the glory years of Quebec pulps — the years between the Second World War and the 1960s, when readers devoured tales of seductive women, rough-and-tumble cowboys, suave Montreal detectives, and a certain French-Canadian ace of spies.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The pulps emerged from a publishing phenomenon created by a small core of hard-working printers, writers, and artists who spotted an opportunity. Through the 1920s and 1930s, French-Canadian readers could get their fix of popular fiction with cheap novels imported from France. But the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 cut Quebec off from the output of French publishers, leaving the low end of the market free for the taking. Currency controls meant that Canadian funds could not be used to buy goods, such as foreign books or magazines, that did not serve the war effort. This sparked a distinctive Quebec literary output that is nearly forgotten today. For three decades, publishers, mainly located in the Montreal region, flooded the book racks of newsstands, drugstores, and tobacconists with thousands of short works of pulp fiction. Though publishers experimented with magazines and anthologies, the most popular format turned out to be stand-alone adventures printed on cheap newsprint, either as sixteen-page booklets that sold for a nickel or thirty-two-pagers priced at a dime.

Focusing on popular genres — crime fiction starring detectives or police officers, spy stories, westerns, romance, science fiction, and assorted adventures — the small books garnered up to fifty thousand readers per title. Around eleven thousand of these stories are estimated to have been published, though the precise total will never be known, since legal deposit — submitting publications to libraries for archiving — was not a requirement at the time, and wartime paper recycling encouraged disposal. The principal historian of the Quebec pulps, François Hébert, estimates that the national libraries of Canada and Quebec have collected about seventy per cent of them; others may reside in private collections. Unearthing them is not easy, as the remaining copies surface in unlikely venues. “These types of publications are mostly found in flea markets and garage sales,” Hébert noted, “very few in second-hand bookstores.”

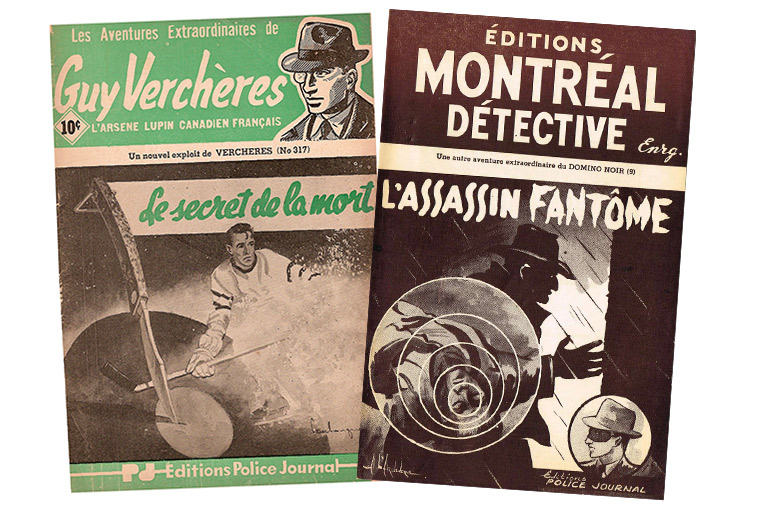

Several series proved long-lasting and popular, with French-Canadian heroes such as detective Albert Brien and adventurer Guy Verchères starring in around nine hundred adventures each. But undoubtedly the most beloved and enduring hero was the spy Jean Thibault, a.k.a. Agent IXE-13.

Agent IXE-13 was brought to life by three men who, in their own way, were as emblematic of the Quebec pulps as the hero they created: writer Pierre Daignault, illustrator André L’Archevêque, and editor Alexandre Huot. Their collaboration illustrates how the pulp enterprise rested at first on a small number of men whose paths crossed in Montreal during the war years.

Huot was something of a mentor for the Montreal pulp pioneers. The son of a shoemaker, he dropped out of law school and began his literary career in reaction to the First World War conscription crisis. Incensed by the army’s killing of four people during a violent anti-conscription riot in Quebec City on Easter weekend, 1918, he wrote and produced an anti-conscription play that same year, adopting the pen name of Paul Verchères. He would later use the same pseudonym to author the adventures of the pulp hero and millionaire turned crimefighter Guy Verchères, dubbed the “Arsène Lupin of French Canada” after the fictional Parisian gentleman thief.

In an episode titled “Feu d’Enfer” (A hellish fire) of Les Aventures extraordinaires de Guy Verchères (The extraordinary adventures of Guy Verchères), our hero finds himself investigating the suspicious case of a woman who has allegedly died of heat stroke on a chilly autumn day. Suspecting her former husband, Boisvenu, of her murder, he coolheadedly confronts the killer:

In the living room, Verchères took out his pistol.

“Boisvenu, I’ ll let you take out the weapon you have in your desk. I’m giving you ten seconds. If you don’t defend yourself, I’ ll shoot you down like a dog.”

Boisvenu didn’t wait to be asked twice. He ran to the writing desk, opened it, and took out the gun.

Verchères counted aloud : “Five, six, seven...”

Boisvenu aimed at Verchères.

Verchères didn’t flinch.

Boisvenu pulled the trigger. The gun fired. The bullet lodged in the door jamb.

Coolly Verchères pocketed his own gun, looked at the bullet hole, looked at Boisvenu, smiled strangely, and said:

“That’s all I wanted to know.”

By 1920, Huot was publishing a weekly newspaper in his hometown. He soon moved into full-time journalism, while still writing plays and fiction on the side. After producing his first play, Huot found a publisher for his later plays and early prose efforts in Edouard Garand, a popular-fiction pioneer who shared his anti-conscription views.

A year after founding his own publishing house in 1922, Garand had started an imprint called Le roman canadien (The Canadian novel), churning out novellas of fifty to one hundred pages that sold for a quarter apiece. In the imprint’s heyday, during the Roaring Twenties, print runs may have reached over ten thousand copies per title. But Garand’s imprint faltered in the 1930s, outcompeted by newspaper serials and paperbacks imported from France. Still, Garand’s mentorship provided Huot with some of the experience he used to create the first pulp magazines and serials of the 1940s.

When writing about crime and composing crime fiction, Huot could also draw upon a different sort of experience: He’d been sentenced in 1939 to a year in prison for soliciting donations under false pretences.

By the early 1940s, Huot had become the editor of the Montreal newsmagazine Police Journal, the city’s leading purveyor of cheap thrills. It combined crime reporting and crime fiction, and some stories were also issued as stand-alone publications. The cheap wartime weekly expanded into a publishing house, Éditions Police Journal, that became so dominant that its known titles are as numerous as those of all other Quebec pulp fiction publishers put together, according to Hébert. It was 1947 when Pierre Daignault came up with an idea for a Second World War spy serial that would become Les aventures étranges de l’Agent IXE-13.

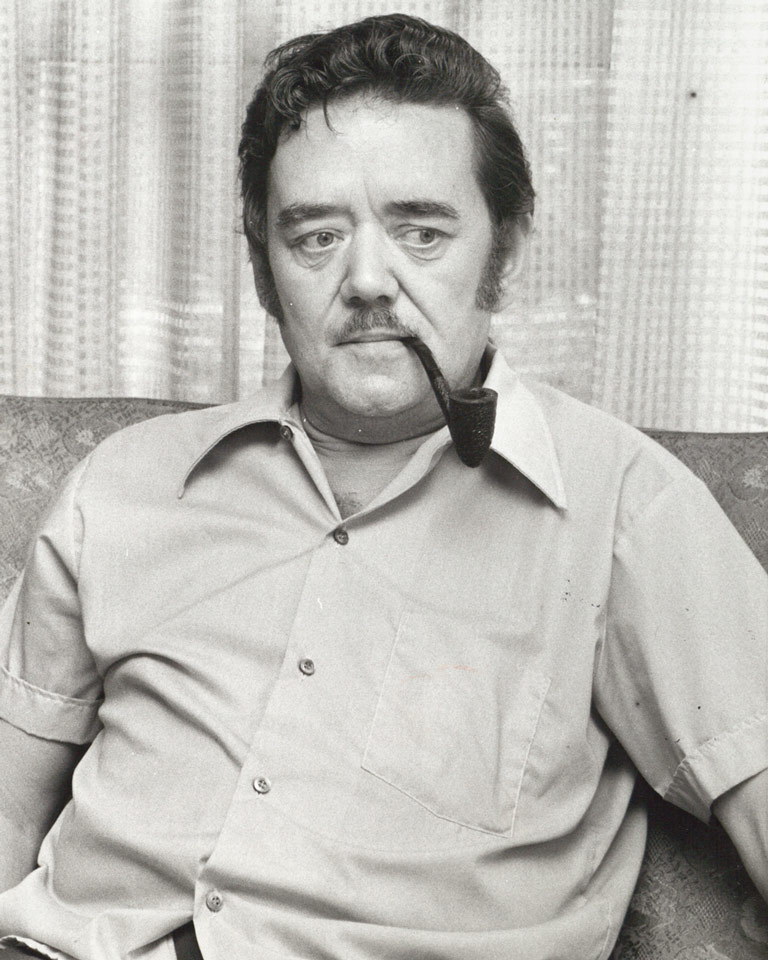

Born in Montreal in 1925, Daignault was the son of the famous actor and folk singer Eugène Daignault. During the Second World War, the younger Daignault moved to Toronto for basic air force training, learning enough English to get by. There, he might have checked out a popular comic strip of the day, Secret Agent X-9, created in 1934 by Dashiell Hammett, the author of the famous hardboiled detective novel The Maltese Falcon, and Alex Raymond, creator of the space-adventure hero Flash Gordon.

After returning to Montreal, Pierre Daignault soon quit a job as a city clerk to follow in his father’s footsteps as an actor, singer, and storyteller. A correspondence course on the art of plotting led him to write for radio and then to approach the printer of Police Journal with his proposal for a spy serial, since he was getting married and looking for additional income.

André L’Archevêque created the IXE-13 logo and illustrated most of the secret agent’s adventures. The son of Montreal printer Eugène L’Archevêque, André was born in 1923, grew up in the same neighbourhood as Daignault, and followed a strikingly similar career path. He attended a Montreal art school, served in the Royal Canadian Air Force during the Second World War, studied architectural drawing, and took correspondence courses offered by New York’s Famous Artists School. A commercial book and magazine illustrator, he created the drawings for an early pulp magazine that was test marketed by his father in 1941, with stories by none other than Alexandre Huot and Pierre Daignault.

Later, Huot and Daignault would each write episodes of a long-running series featuring detective Albert Brien and his wife and partner, Rosette. In one episode, titled “Rosette en péril” (Rosette in danger) our heroine goes undercover to investigate a rum-running ring in the French islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon. After surviving several assassination attempts, Rosette discovers that a man she thought was in love with her is actually the leader of the ring. And now, he has her in his grasp:

“You know far too much now. That’s too bad.”

“What do you mean?” “I missed you several times, but this time I’m going to finish you off, Mrs. Rosette Brien.”

“You know my name! And you asked me to marry you?”

“I wouldn’t have gone through with it. But I really do love you, and I would have let you live a few more days if you’ d said yes.”

“So, it was you all along...?”

“Indeed. I’ve never missed a shot at anyone before you.

That’s why my associates here nicknamed you THE DEVIL’S DAUGHTER.”

“Thanks for the compliment.”

“You’ve lived a charmed life, it seems, but not for much longer.”

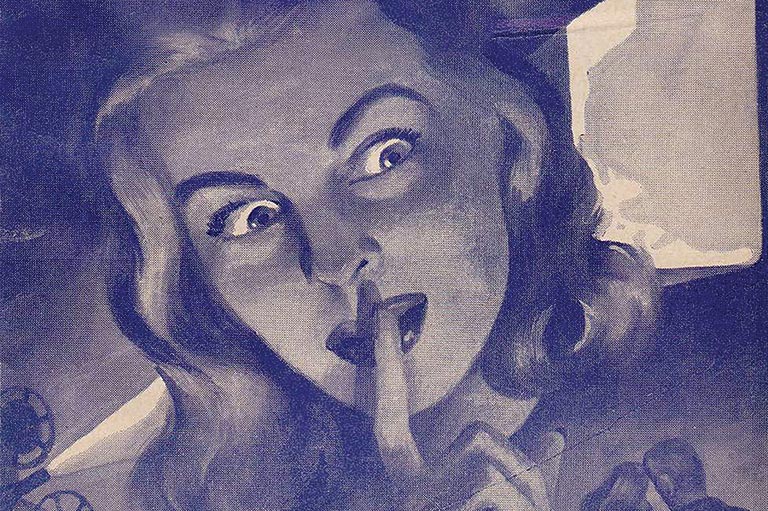

Police Journal and its rivals churned out the pulps on a gruelling weekly schedule. Covers were often repurposed photographs or quickly sketched drawings, tending to the lurid or the suggestive. Much of the best cover art for Agent IXE-13 and many other series was created by André L’Archevêque.

While French-Canadian authors wrote the bulk of the fiction, some publishers recycled stories first published in France. In fact, a story might be published more than once, under a different title, as publishers scrambled to fill a last-minute hole. Characters might reference famous heroes and villains of French popular fiction such as Arsène Lupin, the obvious inspiration of serials such as Les aventures d’André Lupin, gentleman-cambrioleur (The adventures of André Lupin, gentleman-burgler) and Les aventures extraordinaires d’Arsène Lupien (The extraordinary adventures of Arsène Lupien). Even homemade heroes such as IXE-13 had to put up with knockoffs such as the transparently named Spy X-14 and Spy Number 13. The recycling of characters and ideas by other writers or publishers, regardless of intellectual property rights, was part of the game.

In his early years as a pulp writer, Daignault would get up at night with ideas for stories and record them on tape to be sure they would not go to waste. Once he had a plot, he could write an episode in about ten hours of work, though he remembered turning one out in four hours flat. The success of IXE-13 led him to take over much of the writing of the Albert Brien adventures and to pinch-hit on other series, depending on his publisher’s needs. One inspiration launched a female heroine, Diane la belle aventurière (Diane, the beautiful adventuress), one of the few women to headline a pulp action series.

All told, about a fifth of the Quebec pulp stories of that era were produced by Daignault with the support of his wife, Rita Lamontagne, who edited his texts and summarized every week’s episode to help him keep track of previous adventures. While he shared in the writing of other series, he worked alone on IXE-13, with one exception:

“In 1963, I was in a serious car accident,” he recalled in an interview for the 1985 essay collection Le Phénomène IXE-13. “I spent three days in the Saint-Jérôme hospital, in a semi-comatose state. I needed to turn in an IXE-13. [My daughter] Louise would sit by my bedside and, whenever I awoke, I dictated a few pages. I would fall asleep again and then, when I awakened again, I would keep dictating as if I hadn’t stopped. When she typed it up, she realized that the plot was good but that the story was too short, and she added the necessary wordage. That was the only time she helped me, and she was the only person to write, in the whole IXE-13 series, a few lines that weren’t mine.”

Writing under the pen name Pierre Saurel, Daignault banged out about a thousand stories starring Agent IXE- 13. Print runs averaged twenty to thirty thousand per episode — for a total of around twenty to twenty-eight million copies sold. In fact, Éditions Police Journal stopped publishing its Police Journal newsweekly in 1954, presumably because the stand-alone pulp stories proved more popular. Thibault was not only brave, smart, and resourceful — in addition to being an occasional heartbreaker — he also introduced a French-Canadian character in the midst of world events at a time when French Canadians could not look up to many heroes on the global stage.

As Daignault had to keep inventing stories due to the instant popularity of his character, IXE-13 moved on to tackle new foes following the defeat of the Nazis. After the Soviet Union launched the Sputnik satellite in 1957, IXE-13 was sent into space for some Flash Gordon-esque escapades. After roaming the galaxy for nearly twenty consecutive issues, IXE-13 and his companions eventually returned to Earth — and never mentioned their space adventures again.

The Cold War also had Agent IXE-13 confronting communist villains. In episode 950, “Le nouvel allié de Taya” (Taya’s new ally), our hero meets a Chinese seductress:

Not only was IXE-13 the number one enemy of Communists everywhere, but in China there was the powerful Taya, she who had been nicknamed the Queen of Chinese Communists. Taya was known to be an exceedingly dangerous woman. She was unstoppable, a power-hungry glory hound.

She was surely one of the most beautiful women in the whole world and undoubtedly one of the most perverse. She knew that all men dreamed of her and lost their head as soon as they saw her. Taya loved men, and her body was one of her favourite weapons, just as her bed was her favourite battlefield.

How many world leaders and important men had lost their heads as soon as she’ d held them in her arms? They could no longer be counted. Taya was an expert in loving. With a new lover, she lost all inhibition and seemed to be madly infatuated.

Yet, a few moments later, she might turn against him and have him assassinated.

The Quebec pulps appealed to teens but also to white-collar employees and homemakers. Schoolboys would risk expulsion by covertly reading and trading the titillating novels.

Though the pulps catered to a mass audience, they walked a fine line in a province still dominated by the Catholic Church. The packaging often promised forbidden fruit, but the actual stories were much tamer. The Catholic hierarchy despised the entire genre, and the pulp publishers were in no position to court accusations of pornography. In 1946, a Catholic prelate, Monseigneur Valois, condemned the newspapers and magazines preying on the “sensuality” of their readers and the “dime novels found everywhere,” claiming: “Most of these are unequivocally bad and obscene; the rest are not worth the paper they’re printed on.”

An issue provocatively titled “Pénétration nocturne” (Nocturnal penetration) from Éditions Bigalle — whose name referenced the Parisian nightlife hub of Pigalle — served up a cover showing a masked figure entering a sleeping woman’s room. Yet the story offered nothing more than a courtship, with no actual connection to the darkly suggestive illustration and title. For his part, Agent IXE-13 charmed a number of German, Soviet, and Chinese agents, in addition to his long-time fiancée, whom he eventually married.

By the 1960s, the pulps began to run out of steam. The Quebec publisher Héritage was putting out French translations of American superhero comics, while Belgian and French publishers offered cheap paperbacks with better and longer stories. In most Quebec homes, recently bought television sets offered exciting new homegrown series and dubbed American shows.

Huot died in 1953, about a decade before Éditions Police Journal closed in the mid-1960s. L’Archevêque survived on commercial book and magazine illustration for years, then switched in his fifties to figurative painting as an independent artist.

After Éditions Police Journal went out of business, Daignault founded a short-lived publishing house, Éditions Pierre Saurel, which tried to convert IXE-13 and other pulp heroes into playboys closer to the ascendant James Bond model. Though the covers emphatically warned that these were for adults only, sales languished, and the venture ended within the year.

But Daignault had other talents. Unlike more celebrated Quebec authors, he wrote mostly to earn money and never limited himself to penning fiction. From 1949 to 1962 he ran the Pierre Daignault acting company, which staged around seventy-five shows a year in small venues and church halls, featuring his own plays, mostly comedies. He remained active on radio and, later, on television as a performer, caller of square dances, and genial host presenting folk music and tales. In 1960, he replaced his own father in a role on Radio-Canada’s famous television serial Les Belles Histoires des pays d’en haut. He only returned to writing in a major way with a 1980s series of crime novels featuring a one-armed detective, Le Manchot. Still, his later writings never matched the success of his dime novels.

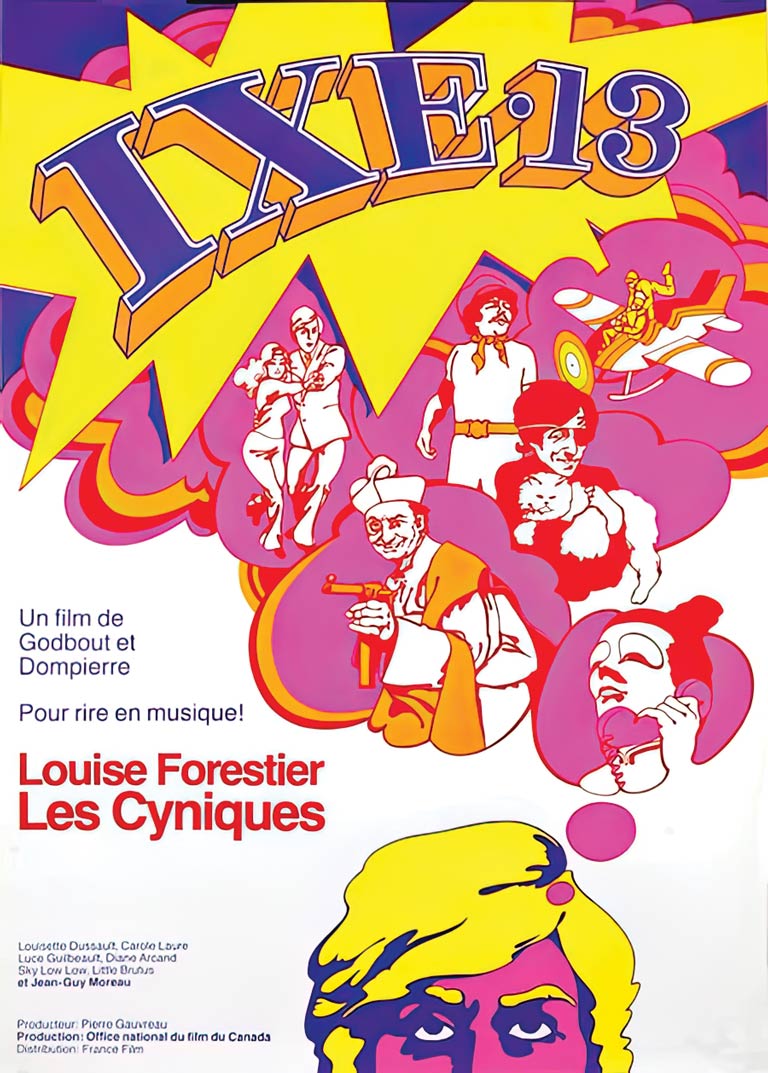

In 1972, the Quiet Revolution’s rejection of many pillars of French Canada’s traditional culture was epitomized by the movie spoof IXE-13. Instead of celebrating an enduring French-Canadian hero, now-legendary director-producer Jacques Godbout produced a mock musical with a bevy of sexy women that satirized the series and its hackneyed plots. An avowed separatist, Godbout slyly lampooned Thibault as a pro-Canadian sellout. Straying from its source material, the movie featured dwarf wrestling, scenes of a shootout in a church, and Bondian borrowings. On the whole, what Austin Powers was to James Bond, Godbout’s main character was to Daignault’s staunch Canadian patriot.

The lasting legacy of Quebec’s pulps might have surprised the baby-boom generation that found its parents’ taste in literature so embarrassingly trite. Despite his detractors, IXE-13 has become a symbol of French-Canadian popular culture in the postwar period.

Recently, Videotron’s Club Illico announced the revival of IXE-13 in an eight-episode television series focusing on Thibault’s return to espionage after the end of the Second World War. In the series, whose release date has not yet been announced, the former war hero runs a nightclub in Montreal’s red-light district, while his partner Marius operates a boxing club, until they are tasked to stop Russian spies from stealing enriched uranium to build the Soviet Union’s first nuclear bomb. Tellingly, scriptwriter Gilles Desjardins confessed to the Journal de Montréal in November 2022 that, thanks to international events, his plot no longer felt so remote — perhaps granting Agent IXE-13 yet another lease on life.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!