Never on a Sunday

In March 1921, Ernest MacMillan was preparing for a special benefit performance of Brahms’s German Requiem at Timothy Eaton Memorial Church. The twenty-seven-year-old choirmaster had arranged for members of three Toronto choirs to sing the work, accompanied by forty-five hired musicians.

Coordinating the singers of St. Andrew’s Presbyterian, Deer Park Presbyterian, and Eaton Memorial Church was no easy task, and it was made more difficult because most of the professional musicians performed at city theatres during the week. Still, MacMillan had managed to book a full rehearsal for the afternoon of Sunday, March 20, just three days before recital.

Then someone warned him that the musicians would be violating the Lord’s Day Act if the rehearsal went ahead. Police confirmed that they would press charges. Nevertheless, representatives of Eaton Memorial vowed to fight, the rehearsal took place, and the recital was a triumph. Ultimately no charges were laid.

As Saturday Night magazine put it, prosecuting musicians “for playing sacred music in a sacred edifice on a Sunday” might well have created a precedent “that sooner or later would involve countless churches who pay professional musicians for exercising their callings on Sunday.”

MacMillan went on to a knighthood and international fame as a musician, composer, and conductor, but the issue of which Sunday activities were legal and which were not confused and frustrated Canadians for decades to follow.

Controversy has long surrounded the weekly day of rest sanctioned by the Bible. In England laws governing Sunday observance included the Sunday Fairs Act of 1448 and An Act for Punishing Divers Abuses Committed on the Lord’s Day of 1625. The enactment of the 1627 Act for Further Reformations of Sunday Abuses proved that, despite the influence of the Puritans, not everyone agreed on what activities were appropriate on Sunday.

Transplanted to the New World, Sunday laws were gradually watered down over the next two centuries. Still, 1845 Ontario legislation outlawed “skittles, ball, foot ball, racket, or any other noisy game,” plus gambling, racing, fishing, hunting, shooting, and a host of commercial activities.

For years, the Ontario law and similar ones in other provinces were enforced sporadically, but by the late 1870s, as more and more people escaped into the anonymity of Canada’s cities, religious reformers were increasingly concerned about Sabbath breaking. In 1888, spearheaded by the Presbyterian church, representatives of various Protestant denominations formed the Lord’s Day Alliance. Its mission was to stop the secularization of Sunday.

Over the next two decades, while ministers raged against Sabbath-breaking from the pulpit, Alliance members demanded prosecutions for all kinds of Sunday activities. Whether the charges ended in conviction depended to a great extent on circumstances, the social class of the offender, and the judge’s interpretation. In May 1895, for instance, V.F. Cronyn, J.F. Edgar, W.J.S Gordon, and A.W. Smith were charged with playing golf on a Sunday. Fined five dollars each in June, the four members of the Toronto Club appealed. Their conviction was overturned in September when a judge ruled:

This game of golf is not a game within the meaning of the law. It is not noisy. It attracts no crowds. It is not gambling. It is on a parallel, it seems to me, with a gentleman going out for a walk on Sunday, and as he walks, switching off the heads of weeds with his walking stick.

Many of the activities targeted were working-class pleasures, including baseball games, visits to amusement parks, or boat cruises. Throughout the Victorian age, churches and social reformers had tried to impose their ideas of respectability on the working class. Enforcement of Lord’s Day legislation was just one instance, but in this case the Alliance was supported by the labour movement, which argued that strict observance of the Sabbath would guarantee a day of rest for working men.

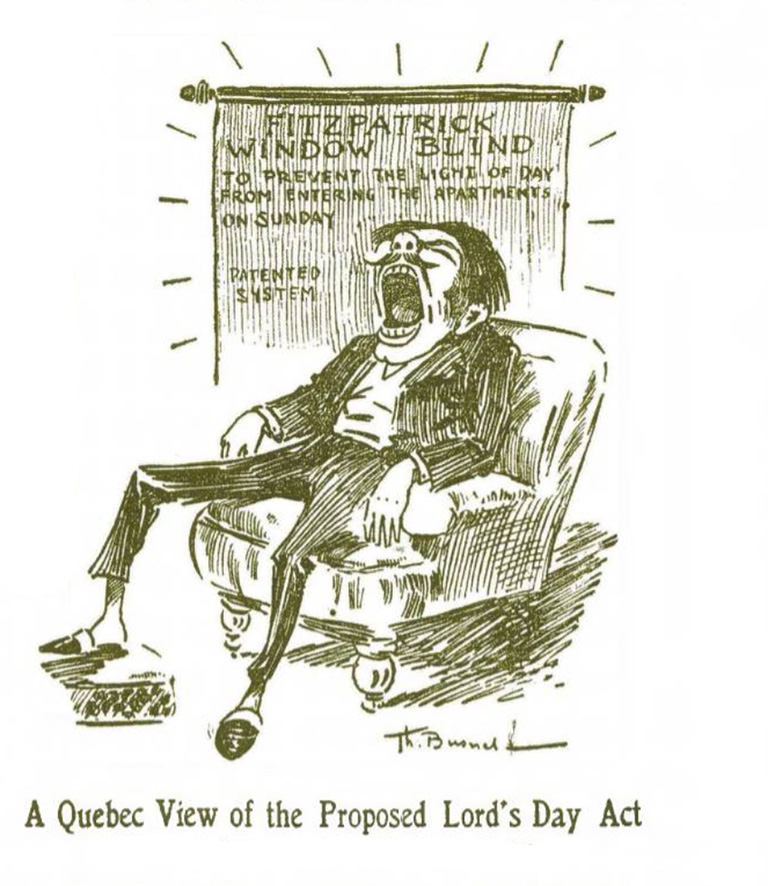

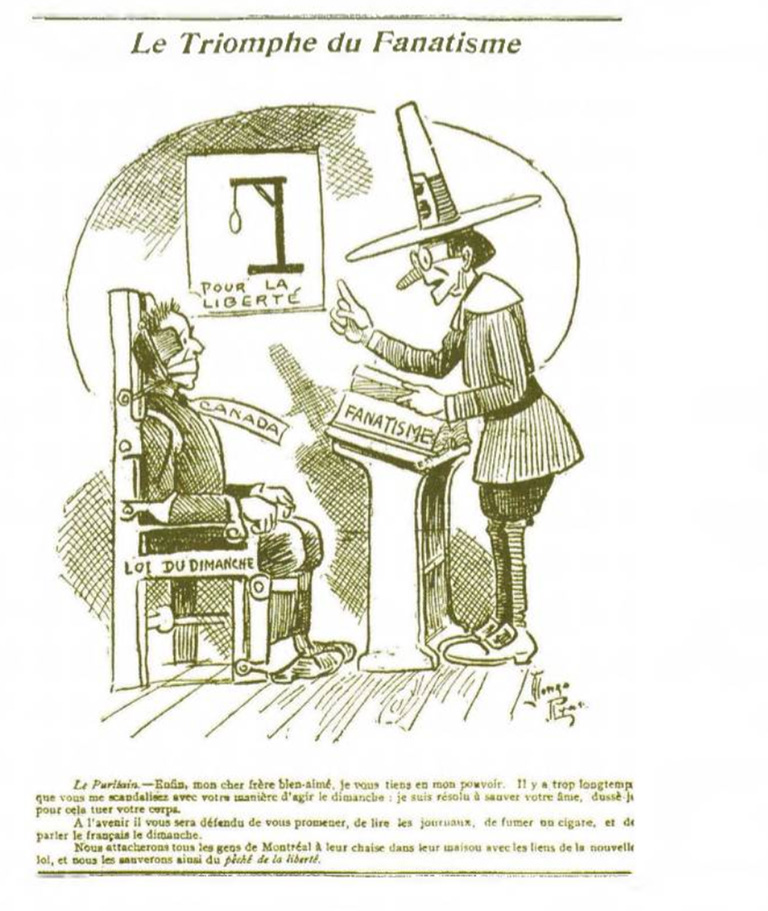

Although Queen Victoria died in January 1901, the spirit of her era survived in Canada for another half-century. In July 1906, the Alliances years of campaigning culminated in the passage of a federal Lord’s Day Act. The issue was bitterly debated. Quebec politician and newspaper publisher Henri Bourassa argued that the legislation violated provincial rights.

He also ridiculed the many exceptions that were built into the proposed legislation, including a clause that allowed Monday papers to be prepared on Sunday evenings and another allowing domestic servants an alternate day off if they worked even briefly on Sundays. To accommodate Quebec’s concern for provincial rights, a key section ruled that the federal act would not supersede any existing or future provincial legislation.

Municipalities were also given discretionary power when it came to prosecutions. Since the new act did not become law until March 1907, Quebec had time to pass legislation that effectively maintained the status quo, permitting Quebeckers many fewer Sunday restrictions than other provinces.

One of the main changes the act brought in Ontario was a ban on the sale of Sunday newspapers. In Hamilton, on the first Sunday the law went into effect, there were few violations. A notable exception was Louis Birk, a news vendor who had stamped his newspapers with the phrase “to be returned Tuesday” and argued that the papers were leased, not sold the court was unconvinced, and because Birk had run afoul of Sunday laws before, he was fined thirty dollars.

The enactment of the Lord’s Day Act brought a number of prosecutions across the country. Within seven years, however, Canada was at war, and while there were occasional complaints, the notion of Sunday as a day of rest took a back scat to the war effort. Canadians, scarred by the horrific experiences of war, but also more sophisticated because of exposure to European culture, became more vocal in their opposition to moral watchdogs.

In 1937, when Captain Archibald Pither of Toronto was convicted of buying a package of tobacco on Sunday, he commented, “Overseas I had to fight as hard on Sundays as any other day.” Sentenced to a two-dollar fine or a day in jail, he took the jail time.

Canadians were especially vocal about uneven implementation of the act. The 1930 Vancouver debate surrounding miniature golf was typical.

Happyland, an amusement area that included a miniature golf course, was not allowed to operate on Sundays, and municipal tennis courts were closed.

But the municipal golf course was open, and the city park board rented bathing suits at English Bay, where hot dog stands and drink booths also operated.

During the debate, Reverend George G. Webber, secretary of the Lord’s Day Alliance, explained that the problem wasn’t with the amusements themselves, but in the precedent that would be set by opening them:

If those who are financially interested in this sport were permitted to make Sunday a regular day for the promotion of their particular type of business on Sundays, then the same privileges could not reasonably be denied to those financially interested in the promotion of ... bowling alleys, billiard rooms, dance halls, theatres, etc. We are not prepared to hand over our Canadian Sunday for the exploitation of commercialized amusement.

But the Alliances power was already waning.

In the wake of another world war and the economic boom that followed. Canadians demanded a variety of Sunday activities, including movies and sports Sam Morris, publisher of a weekly newspaper in the Lake Erie resort town of Port Dover, had lost a brother and a leg in the Great War.

When the Lord’s Day Alliance cracked down on Sabbath violations in his town, he expressed his disgust in an October 1946 editorial:

If you’re just a Common Jo[e] who works six days of the week and only have the Sunday to go to the beach for a picnic — you’re stymied before you start. You must walk and act straight-laced, turning neither to the right nor the left, and don’t think you can come to Port Dover and treat your kids to candy apple - no sir, the Freedom you so nobly fought for and nearly died for is put away for the next war.

Like Sam Morris, Canadians in growing numbers were demanding a more liberal approach to Sunday amusements. In 1945, North Bay, Ontario, allowed commercial hockey games on Sunday. In 1950, both Toronto and Windsor taxpayers voted in favour of Sunday sports.

By 1955, some sixty-nine Ontario municipalities had held plebiscites on the question, with only twenty-seven including Hamilton and Ottawa voting to maintain Sunday restrictions.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

For those who wanted the same range of activities on Sundays as on every other day of the week, there were still main hurdles to surmount. Movie-goers couldn’t see a film in Toronto until the 1960s, and in the 1980s a huge controversy over Sunday shopping erupted.

But, by the 1950s, it was clear that the Lord’s Day Alliance was no longer a power to be reckoned with.

Some cynics suggested that the only reason the Alliance continued to support an outdated law was to stop church revenues from dwindling. Canadians, they said, saw through its facade of moral posturing.

But others pointed to an increasingly secular society as well as to a rise in individualism. As Vancouver lawyer James J. Sutherland said in a 1954 radio debate:

I firmly believe that the Lord’s Day Alliance is composed of high-minded men and women ... And one thing that should be brought home to these high-minded men and women is that one of the freedoms we obtained over the centuries with blood and sweat was the privilege of going to hell in ways of our own choosing.

Forbidden Travel

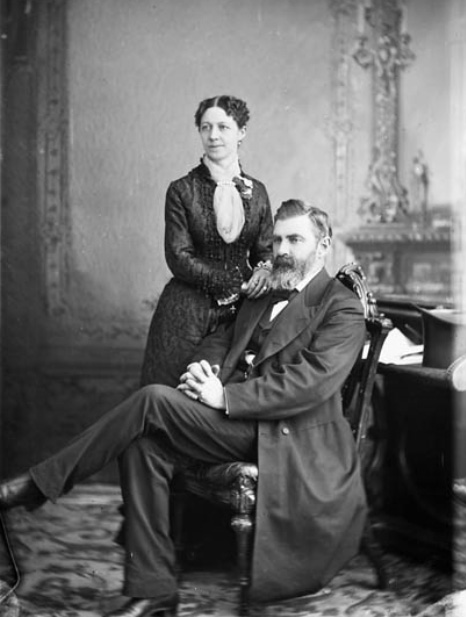

One of the leaders of the Lord’s Day Alliance was John Charlton, a member of parliament who form in the House of Commons.

An American-born Presbyterian, Charlton amassed a fortune as a lumber baron while strictly observing Sundays as a day of rest.

No work was permitted in his lumber camps on that day, and, despite business and political commitments that took him far from his home village of Lynedoch (southeast of London, Ontario), Charlton refused to travel on Sundays.

Other Alliance members were equally adamant. In a 1955 article, Maclean’s magazine recounted how Reverend W.J MacKenzie was travelling from Toronto to Vancouver one Saturday night in 1903.

A missionary, MacKenzie was on his way to catch a boat for Korea, but when the train stopped at a remote spot in the Rockies, he grabbed his hat, coat, and luggage and prepared to disembark.

Questioned by a passenger, Mackenzie pointed out that it was nearly midnight and he had “no intention of travelling on the Sabbath.”

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk necktie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. Made exclusively for Canada's History.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!