Embracing Orcas

Sam Burich, a thirty-eight-year-old Vancouver sculptor, had idled away almost two months at the base of a sandstone cliff on Saturna Island, off the coast of southern British Columbia, before he finally spotted a pod of about a dozen orcas on July 16, 1964. Burich had been recruited by Murray Newman, the director of the Vancouver Aquarium, for a macabre commission: to kill a passing orca and use its corpse as a model to create a life-sized sculpture of the animal.

The sculpture, alongside one of a basking shark — the other apex marine predator of the region — was intended to hang in the high-ceilinged, glass-walled grand entrance hall, the crown jewel of the aquarium’s new $850,000 upgrade. While the aquarium lacked the facilities to hold a live orca or a basking shark, Newman envisioned the impressive replicas in the majestic foyer welcoming visitors in the style of the British Natural History Museum in London, England, or the Field Museum in his hometown of Chicago.

On May 22, when the hunt for the orca began, East Point on Saturna Island had been bustling with personnel. Pods of orcas were known to regularly pass by the island in the Strait of Georgia during the summer months, and a horde of scientists from the University of British Columbia (UBC), the British Columbia Provincial Museum (now known as the Royal BC Museum), and the federal Department of Fisheries (now called the Department of Fisheries and Oceans) had descended to join Burich, along with aquarium officials and the five-man crew of the Department of Fisheries patrol boat Chilco Post. They had set up a swivel-mounted harpoon gun on the shore by the smooth sandstone cliff to target any passing killer whale; but, as the summer wore on with few opportunities to use the harpoon, everyone except Burich had left the island. The lonesome sculptor, who passed the time carving hieroglyphs into the sandstone cliff, was joined at length by Josef Bauer, a twenty-five-year-old commercial fisherman who had been sent to replace the original harpooner. And so, when the long-awaited pod finally swam into sight about twenty metres offshore, Burich and Bauer ran to the harpoon gun and took aim at a small orca who was passing close to the cliff.

The metre-long harpoon found its mark and pierced right through the orca, just behind its head. Ecstatic at first, the pair scrambled into a twelve-metre fishing boat to recover their prize, pulling in the harpoon’s two-hundred-metre line as they approached the whale. But, to the amazement of the novice whalers, the orca kept swimming — very much alive despite the steel harpoon sticking out of its back. Two adult members of the pod held it above the surface so that it could continue to breathe and avoid drowning until it recovered well enough to swim on its own.

Once its podmates had left, Burich shot the whale with a rifle, attempting to end its suffering; however, the orca continued to struggle to live. It writhed around, trying to rid its body of the steel projectile. Meanwhile, alerted by the commotion and by the East Point lighthouse keeper, local residents began to flock toward the scene, some arriving in boats and others crowding the shoreline. By the time a group of local fishermen arrived with rifles to finish off the reviled killer whale, Bauer had been moved to compassion toward the wounded animal. Jumping into a small rowboat, he manoeuvred himself into position to shield the orca from the would-be marksmen. Bauer’s change of heart, and his decisive action to save the whale’s life, triggered a series of events that would alter the course of the species’ existence and change the relationship between the wider human public and the marine mammals described in 1954 by Time magazine as “savage sea cannibals.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

At the time of Burich and Bauer’s escapade, orcas had a reputation as dangerous killers and pests that ate too many salmon. At five to seven metres long, they were too small and had too little blubber to be of interest to commercial whalers chasing great whales like the blue and humpback. Orcas hunted seals and dolphins in packs, harassed and even hunted larger whales — particularly when they had been injured by whalers’ harpoons — and were believed to occasionally attack boats that ventured too close. Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s account from his Antarctic voyage of 1911 of killer whales trying, in coordination, to knock men into the ocean to devour lived on in the minds of modern whalers. Many believed that, since orcas preyed on marine mammals, they would also prey on human beings.

Setting up weaponry to target killer whales was not a new endeavour for the Department of Fisheries. In the summer of 1961 — prompted by fishermen’s complaints that the whales were gobbling up valuable fish — the department had mounted a machine gun overlooking Seymour Narrows, between Vancouver Island and neighbouring Quadra Island. That summer the gun was not fired; in Newman’s memoir Life in a Fishbowl: Confessions of an Aquarium Director, written decades later in 1994, the Vancouver Aquarium director explained that this was due to fears that shells from the gun would trigger forest fires during the especially dry summer. Elsewhere in his memoir, Newman described the public perception of orcas at that time as “the marine world’s Public Enemy Number One.”

Fears surrounding the species had only grown after a disastrous attempt by Marineland of the Pacific, an oceanarium based in California, to acquire an orca off Washington State’s San Juan Islands, about twenty-five kilometres southeast of Saturna island, in September 1962. The orca panicked, wrapping the lasso line around the boat’s propellor. Believing that the whale was attacking the craft, the Marineland staff shot the animal dead and towed the body to nearby Bellingham, where it was rendered into dog food. One of the Marineland collectors kept the whale’s teeth as a trophy.

Tales of that incident may have loomed large in the minds of Burich and Bauer when, floating offshore with a wounded orca on their hands, they called for help from the Vancouver Aquarium. First to arrive on the scene was Patrick McGeer, an inquisitive University of British Columbia neuroscientist who flew in on a chartered aircraft. He was followed several hours later by Newman in a seaplane.

McGeer was also a provincial MLA who would later hold cabinet posts in education and health. He had played Olympic-level basketball, declining a place in the National Basketball Association so he could instead complete a doctorate at Princeton University. He was deeply keen to study the brain of an orca and had been involved with the aquarium’s capture project from the outset. McGeer told CBC Radio’s The Current in 2016 that he wanted to study a brain larger than a human’s. “I reckoned that the killer whale brain would be one of the largest we would ever get. ... This is an extremely intelligent creature.”

When Newman arrived on the scene, he faced a dilemma: What to do with the wounded animal? Newman observed, as he would later write in his memoir, that despite the harpoon the orca “didn’t seem very miserable.” Considering the attachment Burich and Bauer had formed with the whale, as well as McGeer’s excitement at studying a live whale’s brain, Newman made the decision for his two harpooners to tow the orca through the night to Vancouver. With some anxiety, Newman phoned David Wallace, the general manager of the Burrard dry docks in North Vancouver (he had once participated in a prank on Wallace’s father that involved sending him a shark’s head adorned like a roasted pig, complete with an apple in its mouth) and received permission to temporarily house the orca there.

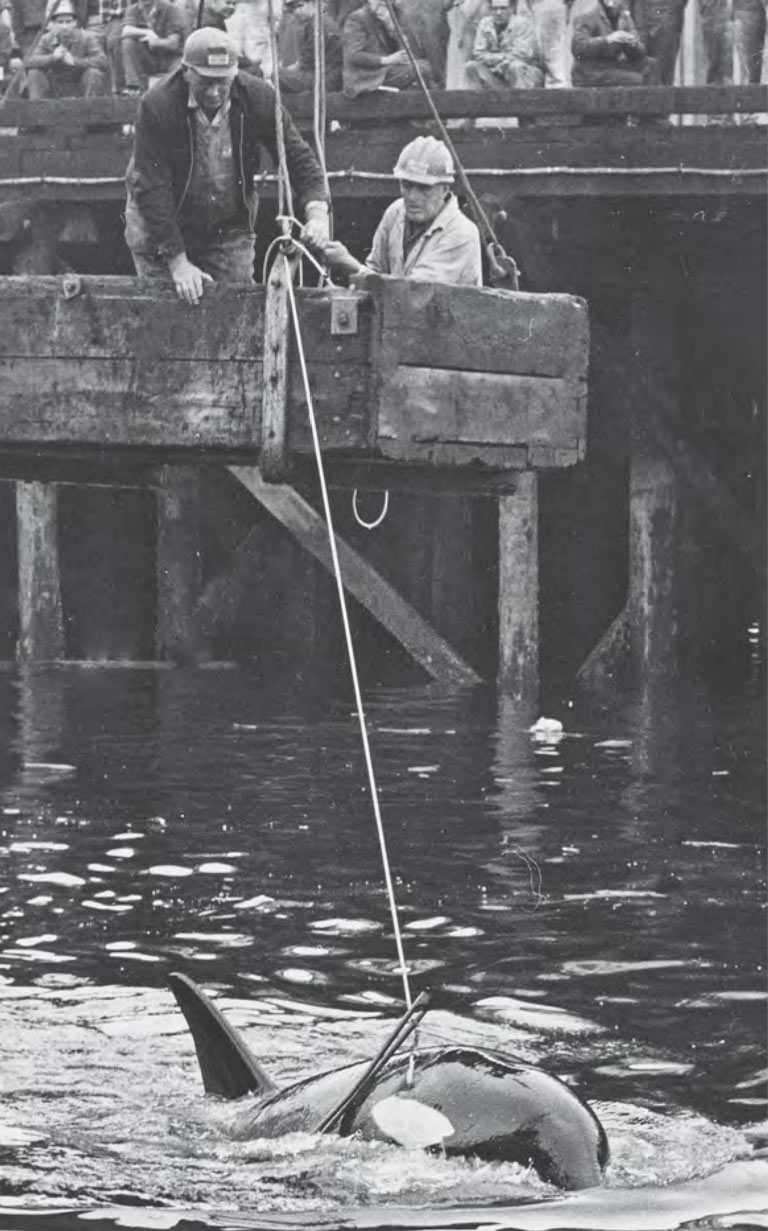

Sixteen hours later, the four-and-a-half-metre, onetonne juvenile whale, tethered by the harpoon line that had passed through the wound in its back, was corralled into the waiting dry dock. A dry dock is a large enclosure that a boat can sail into and that can then be drained of water to allow for the boat’s hull to be cleaned or repaired. In the case of the orca, the enclosure remained full of water, and, with the animal confined, McGeer and an assistant were able to remove the harpoon and to administer antibiotics to fight infection.

On Saturday, July 18, two days after the capture, Newman invited the public to visit the orca for one day only. Twenty thousand Vancouverites flocked to the wharf beside the dry dock. “It was very dramatic,” McGeer recalled in his interview with The Current. “The most feared creature on earth was being towed into captivity. ... So of course that spurred curiosity ... and just huge mobs of [people] gathered around the wharf on the outside, gawking at this killer whale which was just swimming peacefully around in circles.”

The aquarium, founded in 1956, had no suitable home for its popular orca, so a week later six tugboats transported the animal, still inside its dry dock, to a hastily constructed enclosure at the Canadian Army’s Jericho Garrison, ten kilometres away on English Bay. Closed in with chain-link fencing, the pen — one-fifth the size of an NHL hockey rink — was fashioned from the pilings of an abandoned pier. The water depth fluctuated with the tides and was sometimes only three metres deep.

The Vancouver Sun reported that would-be whale watchers climbed fences, pleaded with guards, boated, swam, and, in one case, even floated by on an air mattress to catch a glimpse of the passive whale. One eager visitor was thirty-year- old Edward “Ted” Griffin, owner of a small Seattle aquarium, who broke into the facility to swim alongside the pen and even fed the orca by hand.

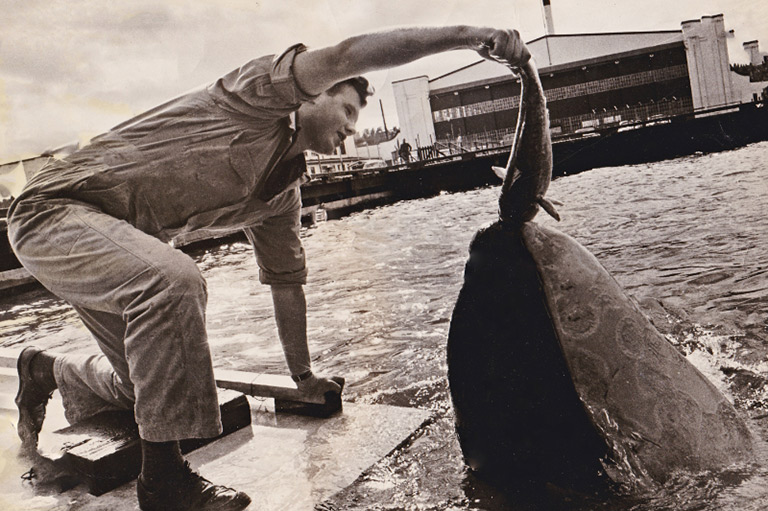

After a naming contest, Newman christened the whale Moby Doll, believing, incorrectly, that the small orca was female. Bauer, desperate to get him to eat, was hired to care for Moby Doll. After fifty-five days of fasting, the orca finally accepted a single fish, then he began to consume up to ninety kilograms of ling-cod and salmon a day. Moby Doll’s keepers were amazed that he could be safely fed by hand.

Burich, now with a live model for his sculpture, spent hours playing his harmonica beside the pen, hoping to communicate with the lonely orca. He whistled to Moby Doll, who eventually recognized the whistle and responded to it — prompting the Victoria Daily Colonist on July 30 to report that the whale had “forgot she was a lady … and whistled to her captor.” The whale never stopped swimming in counter-clockwise circles and occasionally leapt almost clear out of the water.

At his aquarium, Newman fielded calls from academics who flocked to study Moby Doll’s vocalizations, behaviour, and physiology. Two years later, he and McGeer published the world’s first scientific study on orcas, “The Capture and Care of a Killer Whale, Orcinus Orca, in British Columbia.” Belying the animal’s reputation as a man-eater, Newman noted in the paper: “The most astonishing aspect of the [whale’s] behaviour was the complete lack of ferocity or aggressiveness. At no time did it make any hostile moves towards any human involved in the capture, treatment, netting or feeding operation.”

As the summer wore on, Moby Doll became an icon for the city. Hydrophonic recordings made of his vocalizations were broadcast nationally on CBC Radio. Newspapers speculated on whether he would be introduced to U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson on an upcoming visit. Fast-food restaurant Kentucky Fried Chicken ran an ad campaign with the slogan: “A bucket for Moby Doll? A whale of an idea.” Letters to the editor concerning the whale’s fate were constant, some in favour of selling the whale, others lamenting the cruelty of his treatment and calling for him to be released back into the wild, and many celebrating the exciting scientific capture.

While Newman wished to keep his prized scientific specimen in Vancouver, the cost of a new tank, estimated at $500,000, was exorbitant. Mayor William Rathie told the Vancouver Sun: “The city shouldn’t have to provide that much money for a special tank. Visitors only have to take a boat into Georgia Strait to see a killer whale.” A local twelve-year-old’s letter to the editor in the same newspaper countered that “not everyone has the money Mayor Rathie has, and the average Canadian citizen cannot afford to spend $15 or $30 on renting a boat and motoring to Georgia Strait on chance of seeing a killer whale.” Other children sent donations to the newspaper to keep the whale in the city. But a poll conducted by the Sun reported on July 22 that the majority of Vancouverites agreed with the mayor — the cost was too high.

Ultimately, the uncertainty regarding Moby Doll’s future resolved itself in tragedy. On October 9, a month after he started eating, Moby Doll sank to the bottom of his pen and did not resurface. A necropsy revealed that the damage wrought by the harpoon had been more extensive than imagined, although the low salinity of his pen was also blamed: Water with a higher salt concentration is more buoyant, and the effort of staying afloat in the low-salinity environment may have exhausted the young, injured whale. McGeer told CBC Radio in 2016 that he believed pollutants flowing into English Bay from the Fraser River had taken a deadly toll. Today, six decades later, Moby Doll’s skull resides in a small museum overlooking the site of his fateful capture.

In the end, Newman — the man ultimately responsible for the Moby Doll saga — seems to have had conflicted feelings about the creature he’d captured. At a funereal press conference following Moby Doll’s death, Newman told the Vancouver Province that he worried about people sentimentalizing the whale: “It was a nice whale, but it was still a predatory, carnivorous creature. It could swallow you alive.” Yet years later, in his memoir, he wrote of the animal’s death: “I have never felt more futile and forlorn in my life.”

The sculpture of Moby Doll, completed by Burich after the young whale’s death, was hung in the aquarium’s grand entrance hall alongside a sculpture of a basking shark, also achieved by killing a wild animal to use as a model. Newman later acknowledged in his memoir that, from the hindsight of today’s “era of heightened sensitivity for animals,” this method may sound “like a bloodthirsty piece of business.” Yet he noted that for years he had collected, killed, and dissected specimens for his research without drawing any public attention.

As a biologist, Newman had a deep appreciation for aquatic animals, lamenting in his memoir that, in the early 1960s, “species by species, it seemed, marine mammals were either being slaughtered for business or killed as pests. ... Why couldn’t our society appreciate and protect these animals? Obviously, part of the answer was that people knew so little about these fascinating creatures and had no respect for their lives. With so little awareness the general public didn’t care.” For orcas, Moby Doll marked the beginning of an era of awareness.

Newman had a vision to make the Vancouver Aquarium “one of the strongest educational aquariums ever,” and Moby Doll’s brief captivity and sad death helped him to realize that vision, albeit not in the way that he had anticipated — and not without some negative consequences.

The orca-acquisition boom kicked off by Moby Doll took orcas out of the wild, putting populations at risk. The enterprising Griffin, who had snuck an illicit swim with Moby Doll in her pen at English Bay, captured and sold almost three dozen orcas from Puget Sound, in Washington State, to various water parks and aquariums in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1967 Newman purchased an orca from Griffin. Skana, as she was called, lived at the Vancouver Aquarium for thirteen years and was one of seven orcas the aquarium would own as it pioneered a world-renowned educational program that included teams of full-time interpreters and shows of performing orcas, belugas, and dolphins.

The last of the Vancouver Aquarium’s killer whales was sold to an aquarium in San Diego in 2001 after falling ill. In 2018, bowing to public pressure, the Vancouver Aquarium announced that it would no longer house whales, dolphins, or porpoises. In 2019, the federal government made it a criminal offence to keep a whale, dolphin, or porpoise in captivity except for purposes of rehabilitation or licensed scientific research — although an exception was made for animals already held in captivity when the law came into force.

The opportunities for millions of people to see orcas up close arguably spurred the movement to conserve the animals and their habitat. “Before long thirty-two aquariums around the world had killer whales on display, and people were learning about the amazing behaviour of these creatures. It transformed the world, not just about killer whales but about the attitudes towards whales in general,” McGeer said in 2016. “They’re now a protected species instead of a hunted species. So, for complete reversal, this is what the result of Moby Doll was.”

Living off the coast of British Columbia, Washington State, and Oregon, Southern Resident killer whales — the population to which Moby Doll belonged — have been listed as endangered for the past twenty-one years, their numbers decimated in part by aquarium capture programs between 1965 and 1975. A 1974 census counted seventyone members; there were seventy-four as of December 2023.

The last Southern Resident killer whale to be taken into captivity — a female first named Tokitae by her captors, then renamed Lolita, but known to the Lummi Nation of the Pacific Coast as Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut — was caught near Seattle in 1970 and spent fifty-three years at Miami Seaquarium before dying in captivity in August 2023. She was believed to have been born in 1964. While they belonged to different pods, it is possible that she and Moby Doll once swam in the same waters off Saturna Island.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Orcas and People: It’s Complicated

Although the days of slaughtering orcas as pests or capturing them for theme-park entertainment are gone from Canadian waters, humankind’s relationship with this powerful marine predator remains complicated.

In February, experts met in Madrid to figure out what to do about a critically endangered group of forty orcas living off of Europe’s Iberian peninsula who have rammed the rudders of nearly seven hundred boats over the past four years, stranding numerous mariners and sinking at least six vessels.

Noting that the orcas’ behaviour was not aggressive toward humans, the experts speculated that the whales might be playing, or that catching a boat might be a kind of “trophy.” They expressed alarm that some mariners have tried to get rid of the whales by throwing firecrackers or other explosives at them, pouring gasoline or bleach into the water, or hitting the whales with rocks or boat hooks.

“In an ideal world, there would be a simple strategy for mariners to follow when killer whales interact, which would avoid vessel damage and harm to the whales. Unfortunately, there appears to be no such panacea,” they noted in their paper, titled “Workshop Report — Interactions between Iberian Killer Whales and Vessels: Management Recommendations.”

No panacea has been found, either, off the south coast of British Columbia. A study entitled “Warning sign of an accelerating decline in critically endangered killer whales,” published in April in the journal Nature Communications, predicted that the Southern Resident killer whales, currently numbering about seventy-five, are being driven toward extinction by noise pollution, environmental contamination, boat strikes, inbreeding, and the decline of the chinook salmon on which they feed. Efforts to help the orcas — including a salmon-recovery plan and speed limits on ships to reduce noise — may not be enough to save the whales in the face of new dangers, such as the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion that is expected to bring a seven-fold increase in tanker traffic.

Still, there are glimmers of hope. In April, the Ehattesaht First Nation and the Department of Fisheries and Oceans mounted an effort to rescue a young killer whale trapped in Little Espinoza Inlet lagoon, on the deeply indented coastline near the northern tip of Vancouver Island. The whale was orphaned after her mother stranded on a sandbar.

The community named the young whale kʷiisaḥiʔis (pronounced kwee-sa-hay-is), meaning Brave Little Hunter, and fed her seal meat while she learned to hunt on her own. Although rescuers attempted to corral kʷiisaḥiʔis in order to airlift her out of the lagoon, she evaded these efforts and eventually found her own way back to the open ocean.

“Ehattesaht and Indigenous people across Canada are writing new stories in these modern times reinforcing the presence of a deep connection between the spirit world, the animal world, and the people who have remained on the land and waters for all time,” the Ehattesaht First Nation wrote in an official statement. “Events like these have a deeper meaning and the timing of her departure will be thought about, talked about, and felt for generations to come.” — Kate Jaimet

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement