Beaver Tales

Before poutine, maple syrup, or even hockey became synonymous with Canada, there was the beaver. Those tree-felling, dambuilding rodents have helped to shape the environment, culture, and history of modern Canada, but their importance stretches much further back, to the country’s Indigenous peoples and European settlers.

For centuries, people have admired beavers for their construction skills. The dams and lodges that they build make it easy to see why the animal became a symbol of wisdom and industriousness. But it was the beaver’s waterproof pelt that caught the eye of early European explorers who, having depleted their own beaver populations to meet the demand for top hats, realized that they’d found a fresh supply. The resulting profits became a driving force for the European colonization of the land that would become Canada. The fur trade nearly drove the beaver to extinction, but, thanks to conservation efforts and the decline in the popularity of beaver-felt hats, the animal has since made a comeback.

And so, after a long relationship with the beaver, Canada decided to make things official in March 1975 with the National Symbol of Canada Act. To mark the act’s fiftieth anniversary in 2025, we’re showcasing the ever-evolving approaches artists have taken to representing the beaver, and what they tell us about the diverse ways of being Canadian.

article continues below...

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Drawing Connections

Anishinaabe artist Norval Morrisseau’s work depicts traditional stories and spiritual themes about Indigenous culture. A philosophy shared among many First Nations, Metis, and Inuit peoples is the Seven Sacred Teachings, an understanding of how people should live that’s represented by seven animals: buffalo, eagle, bear, sabe (think Bigfoot), wolf, turtle, and beaver. The beaver, which uses its gift of sharp teeth to sustainably alter the environment, embodies the value of wisdom. This 1986 painting, A Group of Medicine Men Receiving Power from the Sacred Beaver, uses flowing lines to connect the animal with the human figures — a common motif in Morrisseau’s art. The lines portray the beaver’s lessons about the interdependence of living beings.

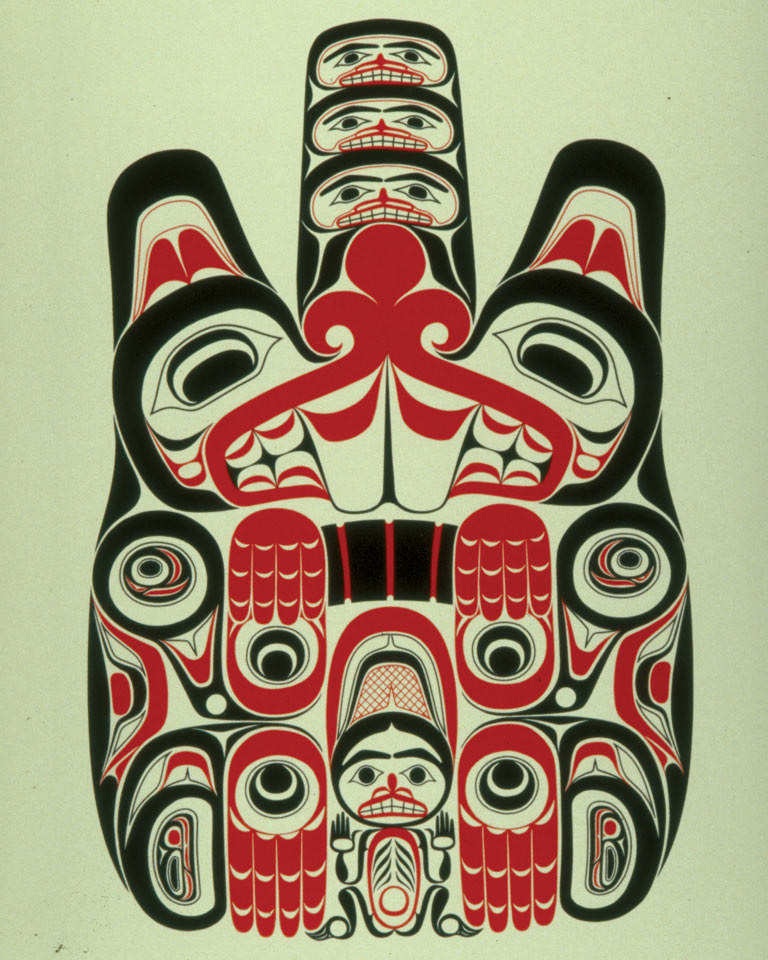

Artistic Lineage

Is prominent incisor teeth, a stick grasped in its mouth or front paws, and a cross-hatched tail that often contains a human-like face identify the beaver in Haida art. In fact, the beaver is one of many crest animals that represent a family’s lineage within the Eagle moiety. All Haida people belong to one of two social groups or moieties, the Raven or the Eagle, and their lineages are reflected in their crests — images or artistic depictions of significant animals. Traditionally, people who display art featuring a beaver are identifying themselves with the lineages and moiety tied to that crest. Here in Ttsaang – Haida Beaver from 1979, Haida artist Bill Reid shows the creature as a symbol of “prodigious renewable wealth” for its association with lakes and streams and the fish found in them.

A Tip of the Hat

It was tough to be cool-headed as the beaverfelt top-hat craze spread among European men of the late sixteenth to early nineteenth centuries, but it was the beaver that was truly under the gun. This hat label from the eighteenth century showed buyers where their fashionable new headwear was coming from: An Indigenous North American on the left hunts a beaver and rabbits on the right; in the centre, a winged figure announces the wealth of beaver pelts claimed by England — represented by the lion standing near a large stack of hats. The label advertises not just the product being sold but also the colonial process that produced it. The message: There is great wealth to be taken from North America, if England can claim sovereignty over the land.

Advertisement

Perspective is Everything

The value of beaver pelts provoked a period of intense violence in North America as various Indigenous and European peoples fought for control over the fur trade. This painting, titled Les castors du roi, was commissioned by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in 2009 to provide an Indigenous perspective on the history of New France, which no thenexisting art could fill. Cree artist Kent Monkman gives European art-of-hunting scenes and colonial wars a parodic twist that highlights the omissions of colonial art. Traditional narratives of intrepid explorers and glorious conquest are unsettled by the tragic yet absurd beaver massacre, posing questions about how art represents Canada’s colonial history. In the figure of the beaver, the human and environmental cost of the fur trade takes centre stage over the vast profits generated in Europe.

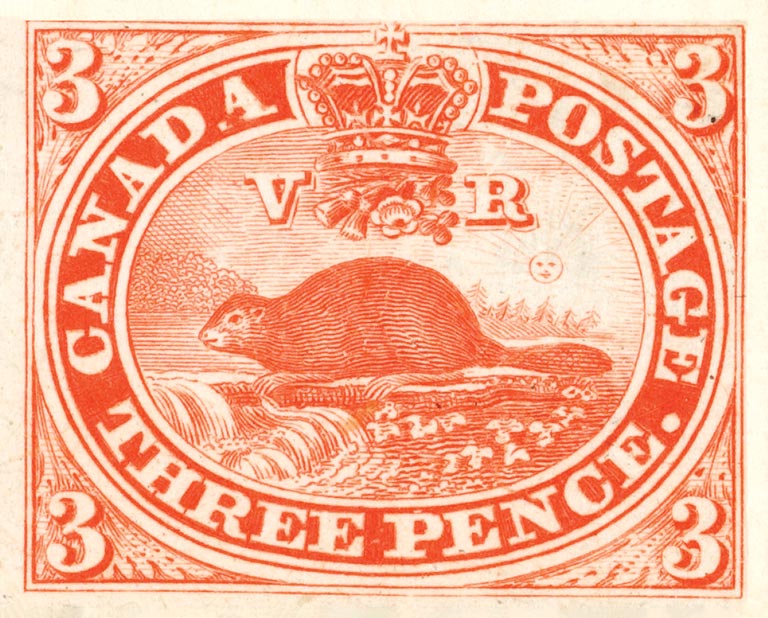

Mailing It In

Not every animal gets its own stamp, and this one was a radical departure from the traditional British approach to postage. Designed by Sandford Fleming in 1851, it’s the first Canadian stamp and the first official stamp to feature an animal instead of a portrait of the reigning monarch. Fleming, who would later engineer large sections of Canada’s early railways, felt that the beaver’s industriousness, building skill, and importance to Canada’s colonial origins made it the perfect symbol for a developing nation.

Picture Imperfect

While the profits of the fur trade were enough to fulfill anyone’s wildest dreams, this 1685 depiction of a beaver was the stuff of nightmares. The Eurasian beaver had been hunted almost to extinction, so many people had never seen one for themselves. Having to rely entirely on second-hand accounts of the animal’s appearance, European artists did not always get the full picture.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Coining It

While the history of the fur trade in this country has long been associated with Hudson’s Bay Company, the organization did have fierce competition. Formed by a group of Montreal-based traders in 1779, the North West Company challenged the HBC’s monopoly on that trade. When competition between the two companies became violent, the British government ordered them to cease hostilities. In 1821, after more than forty years of rivalry, the two companies reached an agreement and merged into a single organization under the Hudson’s Bay Company name.

In its final year, the North West Company began issuing tokens to hunters and trappers in exchange for beaver pelts. Unlike these tokens, though, most of those that survive today have a hole near the top, allowing them to be strung together and worn around the neck for safekeeping. Each token was equivalent in value to a single pelt, an exchange rate that is suggested by the image of the beaver on the token’s reverse side. In the days of the fur trade, the beaver was seen primarily as a natural resource to be exploited for profit, a perspective these tokens represent quite literally.

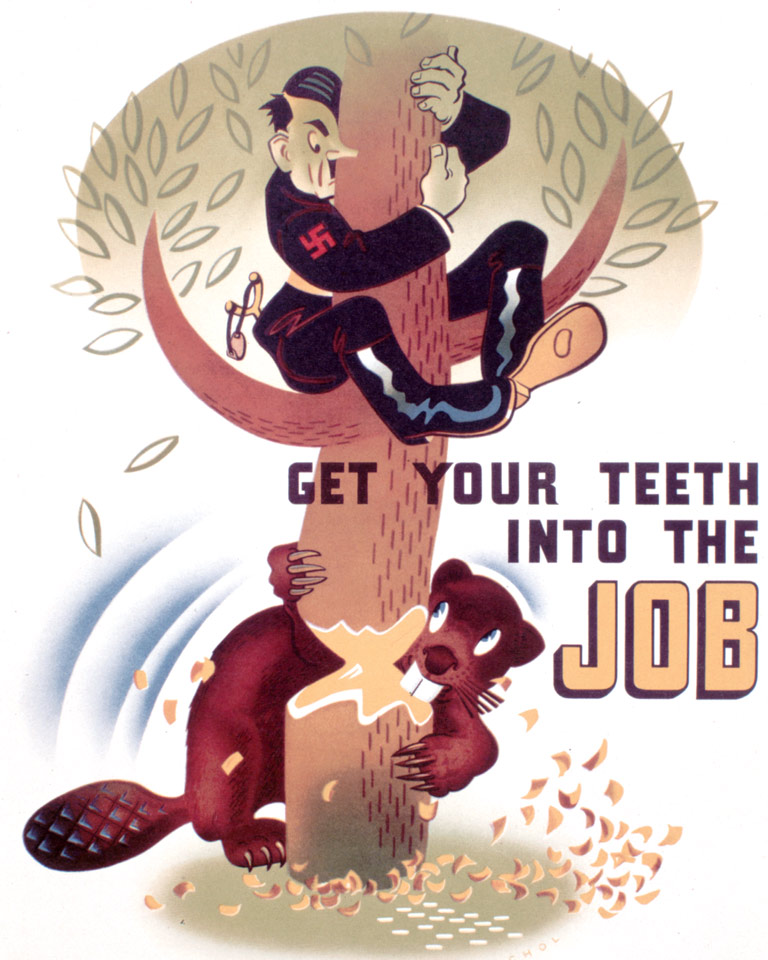

Poster Child

Hitler’s bark was nothing compared with a beaver’s bite, as this propaganda poster shows. Humbler than the British lion or the American eagle, the Canadian beaver amusingly strikes fear in Hitler as he desperately clings to a thinning tree. But the beaver also served as an inspiring symbol for the many Canadians who were contributing to the war effort outside of direct combat. The industrious Canadians once envisioned by Sandford Fleming had as much of a part to play in the war effort as the British and the Americans. This poster tells viewers that war is like any other job, something hard-working Canadians are perfectly suited to tackle.

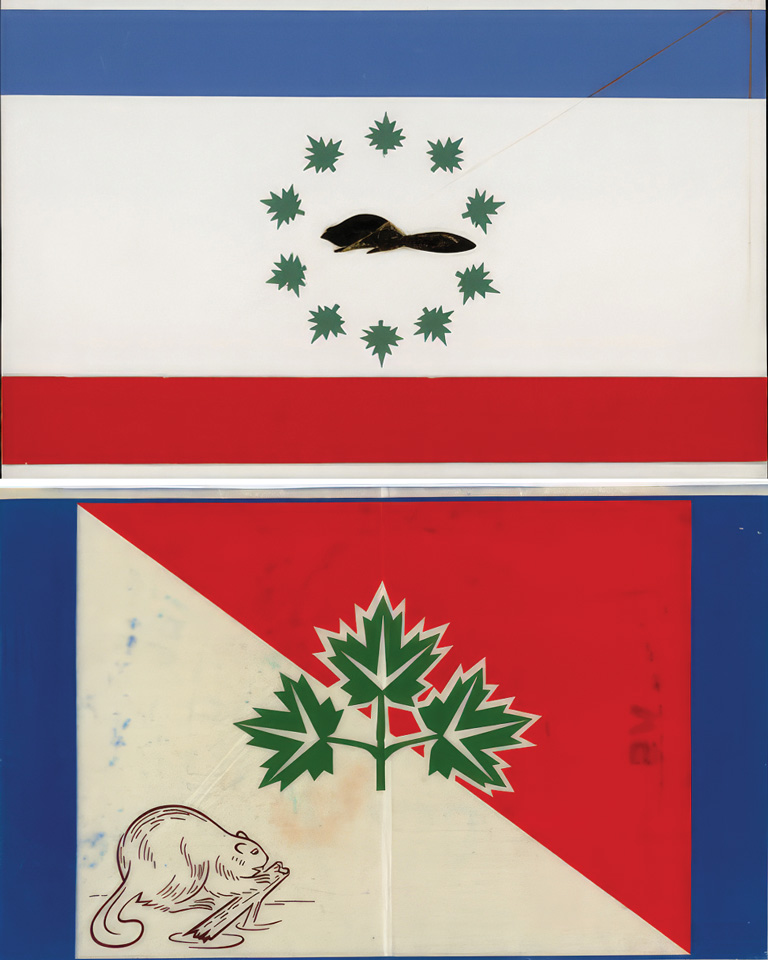

A Flagging Reputation

The Canadian Red Ensign? That’s a red flag! The year 1964 saw many proposed designs for an official national flag, and debates quickly became heated. Among the contested issues was the emblem to be used: The Union Jack? The fleur-de-lys? What about the beaver? As the lynchpin of the fur trade and a common coat-of-arms symbol since the early days of colonialism, the animal, some designers believed, would have been a natural fit. However, the beaver’s importance declined along with the fur trade in the mid-nineteenth century, leading the designer of the current flag, George Stanley, to favour the maple leaf — an emblem of French Canadians that also rose in popularity with English Canadians.

Cue the Movie Soundtrack

Our symbolic animal may often appear as relatively toothless in international depictions — especially when paired with the American eagle. But the national arena is a whole other pile of sticks. In this instance, with the beaver representing the Anglo-Canadian portion of the country, the humble rodent becomes a menacing aquatic predator. In Reshard Gool’s parody of the famous 1975 film poster for Jaws, the beaver preys upon a helpless frog, an animal often derisively associated with French speakers. When symbolizing the imbalance between Canada’s English majority and its French minority, the unassuming beaver becomes a creature with serious bite.

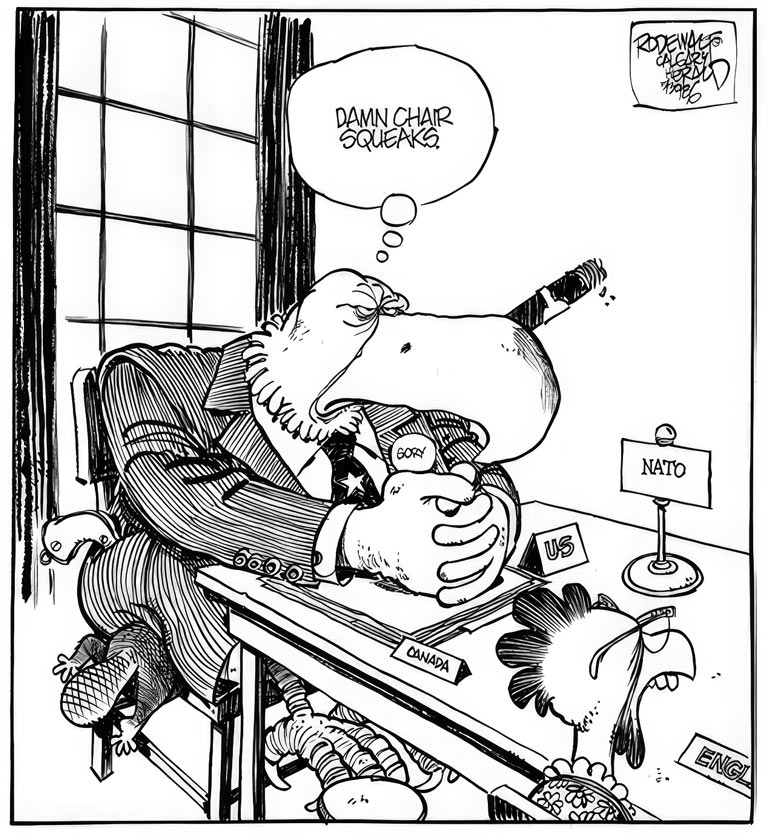

Heads and Tails

It takes an eagle-eyed reader to spot the beaver here. The imposing American symbol takes centre stage, with the weak-beaked English chicken a distant second. At first glance, the Canadian beaver is barely visible. But it’s there — crushed under the mass of the United States. The insignificance of Canada in comparison with the might of America is a theme found throughout political cartoons since the nation’s formation. This 1986 cartoon by Vance Rodewalt for the Calgary Herald accompanied an article on Canada’s opposition to the United States’ decision to break a nuclear-arms agreement. Despite the support of other NATO nations, Canadian protests barely registered with its southern neighbour.

A Coat for the Hats

This coat of arms shows that the beaver was front and centre during England’s early presence in Canada. It was granted to the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1671, the year following the royal charter that brought the HBC into existence and declared that it was to control the area known as Rupert’s Land. This area consisted of over one-third of modern Canada’s land, which the HBC maintained until 1870, when the land was transferred to the Canadian government. The beavers’ central position in the four quarters of the shield suggests their significance to the trade endeavours that were then shaping Canada.

Parking Space

The beaver’s impact on the landscape is second only to that of Canadians themselves. This made the animal a natural choice for representing Parks Canada, the government agency responsible for protecting and presenting the country’s natural heritage. Designed by Roderick Huggins, this image became the first official logo of Parks Canada in 1973 and has been a mainstay of the organization’s branding. Because of its near extinction, the beaver also represented one of the main drivers of Parks Canada’s conservation efforts. To emphasize the animal’s rebound, more recent logos are circular, symbolizing protection and conservation.

On the Money

The beaver design on the five-cent coin we use today entered circulation in 1937 and brought together different periods of Canadian trade history. It was designed by George Kruger Gray, whose work appeared on coins in many parts of the British Empire. Kruger Gray’s beaver had been submitted as the design for the dime, but it wound up on the nickel after the original proposal, the caribou head, was chosen for the quarter. We call the five-cent coin “the nickel” because in 1922 its composition switched from silver and copper to pure nickel, although modern coins are mostly steel with nickel plating. At the time of the redesign, Canada was the world’s leading producer of nickel ore, much as it had been a producer of beaver pelts. This combination of two of Canada’s most abundant resources encapsulated the country’s economic history in a single coin.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement