Gender Terror

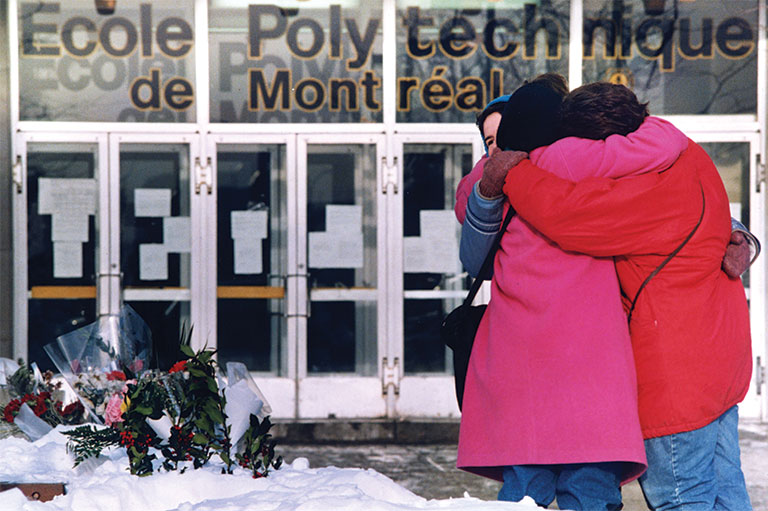

On December 6, 1989 a young man with a chip on his shoulder and a semi-automatic rifle wrapped in a black garbage bag walked into the registrar’s office at École Polytechnique, the Université de Montréal’s engineering school, and slumped into an empty chair. It was a little after four o’clock, cold and snowy outside, and getting dark.

The man, whose name would soon be known the world over, had once tried to enrol in the school but had been turned away. On this day, however, he had not come to enquire about further studies. Marc Lépine, the man known today as one of Canada’s most notorious mass murderers, knew full well where he was heading.

He’d bought an assault weapon, rented a car, written a note instructing his mother to take the refrigerator in his small east-side apartment, and, on the afternoon of December 6, driven to the prestigious university perched high on the mountain in the centre of the city.

He had planned everything down to the last detail, including hastily writing down the reasons for his actions and tucking the note in a pocket where it would be found. And yet, there he sat in the registrar’s office, the hour ticking away, as if he were waiting for divine intervention.

Did he secretly hope that fate would intervene and foil his plan? Or was he mentally rehearsing what was to come?

When a receptionist finally asked if she could help, the surly intruder left the office and headed for a classroom. His semi-automatic weapon now in full sight, he walked in and told the teacher and male students to vacate the premises. They all did, without a protest, thinking that this was some kind of end-of-semester prank.

Turning to the nine women left in the room, he yelled, “You’re all feminists!” and started shooting.

Lépine continued his spree down the halls, through the cafeteria, and to a second classroom, sometimes shooing the men out of the way to make sure he shot only women. Silently now, never uttering a word, he continued his grim task. His only communication was the words “Oh shit” (in English) that he hastily scrawled on an exam paper minutes before shooting himself in the head.

That, too, was part of the plan. He’d brought a hunting knife along to make sure he’d have enough bullets for himself. His last victim — the daughter of a Montreal police officer who would stumble upon the gruesome scene only minutes later — was found stabbed multiple times in the chest. For sure, there was method in this man’s madness.

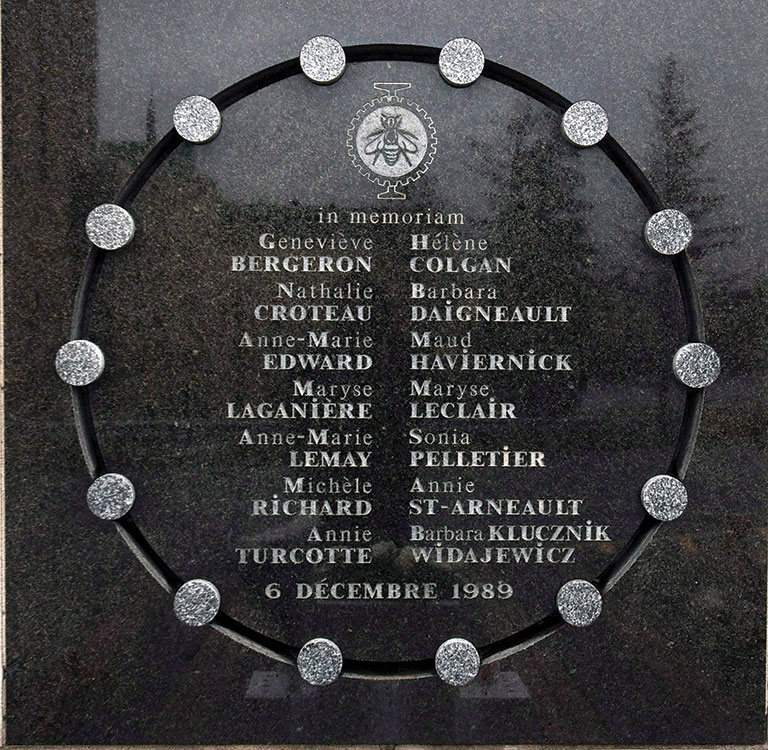

At 5:15 p.m., fourteen women lay dead and fourteen others, mostly women, were injured. Lépine’s murderous rampage, carefully planned and meticulously executed, had taken less than twenty minutes.

Nothing quite so ugly had ever happened in Canada, certainly not on this scale, and nowhere in the world had women been publicly singled out during a recent mass attack.

Advertisement

The combination of cold-blooded murder performed like some grim piece of theatre on a university campus and of female engineering students being hunted down like animals, with all of this unfolding in a province known for its progressive politics — it was too much for most people to bear.

Much like the assassination of John F. Kennedy in the United States, what became known as the Montreal massacre is a defining moment in Canada’s history and perhaps especially in Quebec’s. Everyone knows where they were when the unthinkable occurred. Everyone is aware of a before and an after, of a sudden and wrenching loss of innocence.

I was at home, in Montreal, when a friend working at the local CBC station, David Gutnick, phoned to say that “women were being shot” at the university. I remember little else except sitting glued to the television screen.

I was part of the collective stupor that grabbed the city, the province, and, indeed, the entire country that night. How terribly naive we’d been, I remember thinking. How could we not have seen that there would be a price to pay for feminism?

How could we not have understood that upsetting traditional hierarchies, demanding radical change, would infuriate at least some people? How could we not have expected, if not a horrific attack — who ever expects the unimaginable? — then at least a backlash of sorts?

Until then, I had never realized how uneventful the path toward women’s liberation had been. The notion that women deserved to go where only men had gone before had not been met, curiously enough, with fierce resistance.

Feminism had been widely accepted, in part because of massive organizing, yes, but also because its time had come. When the wind is blowing strongly in one direction, reactionary voices tend to keep quiet.

But now a disgruntled twenty-five-year old named Marc Lépine had broken the seal that had kept resentment regarding feminism safely under wraps.

Those were some of my thoughts at the time. They were not widely shared. In the gloomy light of the Montreal massacre,the general feeling was that we had witnessed an aberration, a horrid blip in an otherwise edifying narrative, an exception to our good rules and behaviour.

Clearly, the assailant was a lunatic, as the psychologist interviewed on Radio-Canada television professed that night. That hypothesis was met with wide approval and would be repeated for years to come.

Despite the fact that the Montreal police had mentioned a “grudge against feminists” — implied in the note Lépine had pinned to himself as well as in the cry he uttered in the classroom — the perpetrator of such a horrific crime had to be demented. End of story.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

There was a strong urge at the time simply to drop the curtain on something no one had seen coming and that in no way fit the image we have of ourselves as a people and as a country. Sudden outbursts of unforeseen villainy not only trigger shock and confusion, they trigger a good deal of denial as well.

In Quebec, where the shock was greatest, the tendency to look away was painfully obvious. Not only did the Montreal police never release Lépine’s suicide note, the only piece of evidence able to shed any light on his motives, but no special inquiry was ever held on the subject of the Montreal massacre.

While Canada had never experienced a gender-specific mass murder, there was no special investigation into the circumstances surrounding the tragedy, other than routine police inquiries.

More than they were repulsed by the actual bloodshed, people instinctively recoiled at the idea that a young man had wanted to kill young women. The idea of singling out women, because they were women, was so insufferable that an editorial in Quebec City’s Le Soleil newspaper went so far as to deny that it had anything to do with gender.

The murder of fourteen women was a tragic coincidence. Un point, c’est tout — period; that’s it. Let us grieve the dead was the subtext, but by no means let us try to give this freak occurrence any greater meaning.

Though denial in the rest of Canada was never so blatant, the fact that women had been specifically targeted remained a point of contention all over the country. Following the Montreal massacre, many university campuses erupted in heated arguments between male and female students.

Women felt vulnerable like never before and wanted their feelings acknowledged. “Now do you see what it’s like to be a woman?” was an often-heard gibe. For most men, however, the grisly murders could not be held up as a mirror of women’s experiences. It was too far-fetched.Women felt abandoned by men, and men felt unfairly scapegoated and belittled by women.

The best of times had suddenly morphed into the worst of times. All of the efforts to tune out Lépine’s anti-feminist message had not stopped his venom from seeping out. The mad crusader had succeeded, momentarily at least, in pitting men against women, at creating acrimony and suspicion between the sexes at a level rarely seen.

From this moment on, as if finally given a green light, male resentment against feminism would come out of the closet. Men’s rights groups like Fathers4Justice would take the stage, and the women’s movement would go into a fifteen-year slump.

Lépine’s suicide note was sent to me anonymously by mail on the eve of the first anniversary of the Montreal massacre. After discovering that my name was among those of eighteen other women included in his suicide note, women who seemingly exemplified what he hated about feminism, I had tried to get the note released.

What had happened at École Polytechnique was not just another bit of sordid news, I argued, first to the Montreal police and later to an access-to-information board. It was a national tragedy. People had the right to know what the motivating factors were behind this unprecedented crime. I also felt that I had the right to know what Lépine’s thoughts had been just before killing fourteen women while having me, and others like me, in mind.

My arguments had fallen on deaf ears. The danger of a copycat crime was too great, I was told. What was in fact “too great,” it was clear even then, was the trauma. Even six months after the tragedy, we were still in the grips of a vast emotional paralysis. The inclination was to “move on,” rather than to scrutinize every detail.

Save as much as 52% off the cover price! 6 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital.

Now, finally holding the much-sought-after piece of evidence in my hand, I felt somewhat vindicated. At least someone at the Montreal police thinks I’m right, I thought. I was never able to discover who that person was, but at least the suicide note would now be made public. It was published the very next day, on the front page of La Presse, the newspaper for which I wrote at the time.

“Feminist attitudes have always made me rage,” the killer went on to explain. Calmly, dispassionately, even taking the time to apologize for his bad grammar, Lépine decried how women expect the same privileges as men but still want to be coddled.

“Even though the media will label me a Crazed gunman, I consider myself a rational erudite,” he added in a somewhat prophetic note.

Had this clumsy one-page manifesto been released at the time, I’ve often wondered, would we have been better able to stare the devil in the eye? Would we have been able to admit that this was not only a vicious attack against women but a war against feminism, as Lépine himself took pains to point out? Would we have labelled him, as he should have been, a terrorist? Someone who kills innocent people for political reasons is, after all, the very definition of a terrorist. Would we have acknowledged the political nature of this gender-specific crime? And would we have been better at understanding what this was all about?

Thirty years after the fact, many candles have been lit, white ribbons have been shared, some assault weapons have been banned, and denunciations of violence against women have become a yearly ritual on Parliament Hill and elsewhere. It took some time, particularly in Quebec, but we have collectively owned up to the fact that this was indeed a crime against women.

And yet, I can’t help feeling that we still haven’t learned the lessons of the Montreal massacre.

In trying to make sense of this horrible tragedy, we have equated the plight of the victims with the violence women have always endured. We have put this in the category of what we know, rather than what we don’t know. I think this was a mistake. By never focusing, to this day, on the truly unusual aspect of the crime — an attack on feminism — we have been prevented from seeing what’s at the bottom of this, as recent events have now underlined: men’s access to women’s bodies.

I’ve thought a lot about the Montreal massacre over the last thirty years. I’ve written about it extensively and directed two documentaries on the subject.

Quickly, I came to suspect that Lépine’s outrage vis-à-vis feminists was rooted not so much in the societal transformation brought about by women’s liberation as in his own personal frustration with women.

A classic mass murderer in many ways — young, white, male, with a terrible axe to grind, convinced that he deserved better in life and hell-bent on making innocent people pay — Lépine was a glum introvert who did not interact easily with people, especially women.

He’d been abandoned by his father at a young age, bullied by his sister, his only sibling, and kept at a distance by his mother, a pious woman who had once wanted to become a nun and worked long hours as a nurse. He harboured ill feelings for the two women, his only close family, and, at age twenty-five, had never had a girlfriend.

I believe the Montreal massacre gave us our first clue that the real sticky wicket when it comes to feminism is not that women will be allowed to do men’s work. The problem lies on the interpersonal level.

There is no danger in having women engineers, in other words, as long as men-women relationships, society’s touchstone, remain the same — as long as women remain physically and emotionally available to men.

I suspect that Lépine instinctively knew that the more liberated women were, the less likely they would choose a man like him — angry, reactionary, forlorn. Feminists were not so much taking up his space as denying him the emotional and sexual companionship he craved.

Lépine was in fact a trailblazer for those irate men who today blame “vicious” women for their forced celibacy. The perceived lack of women’s availability is what lies at the heart of the so-called Incel (involuntarily celibate) Rebellion, which has been responsible for two recent lethal attacks, one in Santa Barbara, California, in 2014, and another in Toronto, in 2018.

Both Elliot Rodger and Alek Minassian were incensed that women were denying them what they were “owed”: a proper sex life.

Women’s availability is also at the heart of the sexual harassment pandemic that has inspired the #MeToo movement.

From CBC Radio host Jian Ghomeshi to Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein, International Monetary Fund director Dominique Strauss-Kahn, comedian Bill Cosby, and PBS interviewer Charlie Rose, the list of powerful men who have been accused of sexual misconduct just keeps growing. The extent to which men — highly respected ones, to boot — continue to avail themselves of women’s bodies is truly astounding.

It prompts the question: How does this square with feminism? How can we have more and more strong, educated, independent women, on one hand, and an astronomical level of groping, raping, and lewd conduct on the other?

Might there be some kind of trade-off here? Women get to become public figures, maybe even run a country, in exchange for sexual compliancy, in exchange for male dominance on an intimate level. And if that means getting a little roughed up in the process, so be it.

Could that be the unwritten rule that explains both the degree of sexual misconduct we are witnessing today and the deadly outbursts that occur when this secret pact is perceived to be broken?

In the persistent gloom cast by the Montreal massacre, I’ve come to the conclusion that we’ve underestimated the personal costs related to feminism.

We’ve had a tendency to think that if we tackled the big picture, changed laws and social structures, the rest would take care of itself. But the rest, what happens on a personal, psychological, and emotional level, is much more resistant to change, it turns out, as well as ultimately more complicated.

That, for me, is the true lesson of the Montreal massacre.

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement