Whale of a Tale

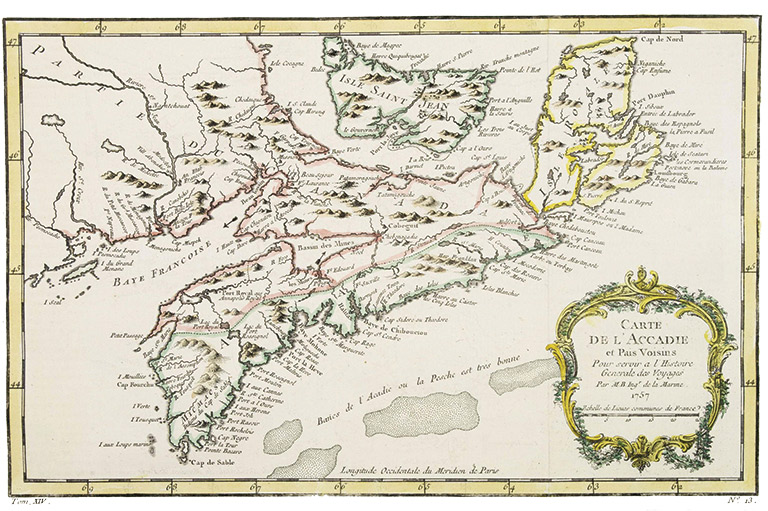

The quiet fishing town of Red Bay, Newfoundland and Labrador, population 264, is not a place most Canadians could readily find on a map. But in the sixteenth century, Gran Baya, as it was then known, bustled with activity as the centre of the largest whale oil production facility in the world.

Basque mariners from northern Spain and France came by the hundreds to what is today the Strait of Belle Isle off the coast of Labrador to hunt bowhead and North Atlantic right whales. As many as fifty ships, each with a crew of fifty to seventy-five men, would cross the ocean each spring and remain for eight months every year from the 1540s to the early 1600s.

From their network of shore stations, which included rendering ovens, cooperages, workshops, temporary dwellings, and wharves, they set about rendering the blubber into oil and assembling the wooden barrels needed to bring the commodity home to Europe. Whale oil was once a valuable lighting fuel (it burned brighter than the more common vegetable oils) and was also used in a wide range of other products including paint and soap.

This intriguing chapter in Canada’s history was all but forgotten until the 1970s, when historical geographer Selma Barkham, who was researching Basque archives, found vague references to whaling in Labrador. By 1979, Red Bay became a National Historic Site of Canada. In June 2013, it received worldwide recognition as a UNESCO World Heritage site for being the earliest, most comprehensive, and best-preserved archaeological testimony of a pre-industrial whaling station.

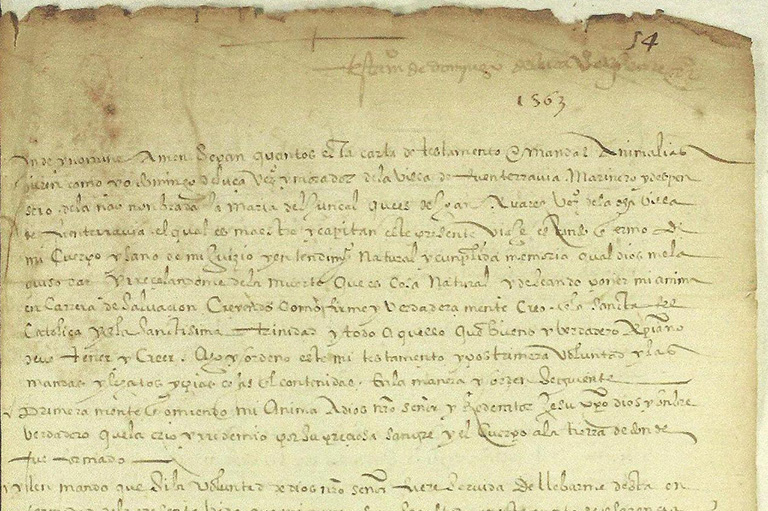

Thousands of artifacts connected to the life and work of the sixteenth-century Basque whalers in Canada have been found and put on display in the visitor orientation centre in Red Bay and the nearby visitor interpretation centre. Items include harpoons, wooden plates, clothing, and the earliest known original will written in Canada. Dated June 22, 1577, the last will and testament of Juan Martinez de Larrume asks that monies be donated to various church causes and details names of those to whom he owes money and those who owe him.

Other important artifacts remain below the surface of the bay, including three Basque galleons and four small whaling craft that are generally considered to make up one of the most precious underwater archaeological sites in the Americas.

One of those smaller boats, an eight-metre-long wooden vessel called a chalupa, was brought to the surface, restored over a twelve-year period, and now sits on display in a temperature-controlled environment at the orientation centre.

The Basque mariners set up most of their operations on Saddle Island — a one-minute boat ride away. On this tiny, tranquil island, you can hear the calls of herring gulls and black-backed gulls that nest on the opposite side of the island and see the highly prized cloudberries (known locally as bakeapples) ripening on the grassy hills in the summer.

Visitors, who are few in number, can follow a narrow, meandering dirt path dotted with thirty-four markers indicating various historic Indigenous and Basque sites. Most are now just depressions in the ground. They include the locations of numerous "tryworks" — used to hold and heat copper cauldrons in which whale blubber was melted — and a cooperage where barrel makers worked and lived.

The trail winds past a rusted, half-sunken French ship, the Bernier (a recent wreck that sank in 1966). Hidden beneath the waves nearby is a galleon loaded with eight hundred barrels of oil, which broke its anchor during a storm in 1565 and sank in Red Bay harbour. The sunken ship, believed by some to be the San Juan de Pasajes, was discovered in 1978. Over the course of seven years, experts dismantled the ship, recorded its inventory, and then returned it to the harbour. A small‐scale model of the ship, as well as artifacts recovered from the wreck, are on display at the site.

At the western end of the island is a cemetery that holds the remains of 140 whalers buried in sixty graves. It is believed that many of them died from drowning or exposure. The graves are marked by large stones, some of them arranged in a row.

By the early 1600s, the Basques mariners abandoned the Labrador coast. Whether it was due to the decline in the whale stocks, or some other reason, no one knows for sure.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Help support history teachers across Canada!

By donating your unused Aeroplan points to Canada’s History Society, you help us provide teachers with crucial resources by offsetting the cost of running our education and awards programs.