999 Queen Street West: The Toronto Asylum Scandal

“Exceedingly handsome, commodious, healthful and safe…a monument to the Christian liberality of the people,” wrote Toronto Globe editor George Brown of the new Provincial Lunatic Asylum in 1850. He optimistically viewed it as a true asylum, “where disturbing influences are absent—not a mere hospital or prison—where every good part of human nature is brought into play.”

Within a few short years, however, Brown’s attitudes radically altered. An old political adversary, Dr. Joseph Workman, was named head of the institution. Brown soon became a harsh critic, most severely in February, 1857, when the Globe published an attack on the moral character and medical competence of the Medical Superintendent. Dr. Workman was guilty of “villainy, deceit, and tyranny,” wrote a disgruntled former hospital porter, James Magar. Calling himself “the moral Sentinel of the Asylum,” his letter was headlined by the Globe, “Recent Disgraceful and Outrageous Doings at the Provincial Lunatic Asylum.” Magar outlined a number of alleged incidents of sexual misconduct, inadequate security, physical harassment, and administrative mismanagement. The letter ended with this comment: “He [Workman] has been sustained by the present corrupt government from graver charges, and until the moral pestilence of his superintendence stinks in the community, he is likely to continue his villainy and outrage.”

Dr. Workman responded by immediately suing Brown for libel, seeking damages of five thousand pounds.

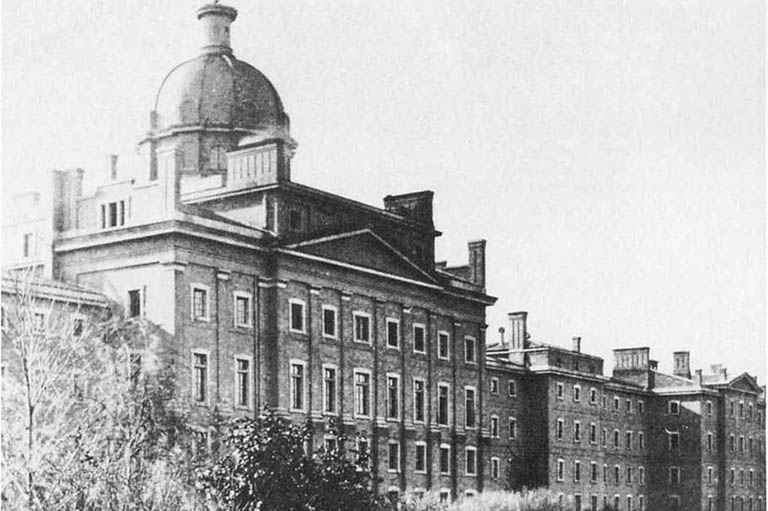

The opening of the Provincial Lunatic Asylum in Toronto in 1850 was the climax of a long political struggle, and marked a major change in attitude toward the treatment of the mentally ill in Upper Canada. In the early years of the province, there was no provision for the insane. “Quiet lunatics,” as one authority dubbed them, were confined at home, while “furious lunatics,” those more of a threat to persons or property, were consigned to jails. In 1830 the magistrates of the Home District called for some more humane form of treatment. After nine years of wrangling, the legislature authorized “the erection of an asylum within the Province for the reception of Insane and Lunatic persons,” and temporary provisions were made at the old Toronto jail. Negotiations for a permanent facility began, but continued squabbles meant more delays. It was not until 1845 that construction began on the building (later notorious as “999 Queen Street”), designed by the noted city architect John George Howard. Five more years passed, however before the asylum, only half complete, opened its doors.

The new hospital was situated well outside the city, in a large open area on the lake shore. It was intended to be a sanctuary, a safe place, for persons who were suffering. Inmates were to be treated as patients, there to be cured in an atmosphere of cleanliness, kindness, decency and compassion. The impressions of Susanna Moodie, visiting Toronto in the autumn of 1852, well captured the new attitude:

The asylum is a spacious edifice, surrounded by extensive grounds for the cultivation of fruits and vegetables… (with) ample room for air and exercise… Ascending a broad flight of steps, as clean as it was possible for human hands to make them, we came to a long wide gallery, separated at either end by large folding-doors, the upper part of which were of glass; those to the right opening into the ward set apart for male patients who were so far harmless that they were allowed free use of their limbs, and could be spoken to without any danger to the visitors. The female lunatics inhabited the ward to the left… The long hall into which their work-rooms and sleeping apartments opened was lofty, well lighted, well aired, and exquisitely clean; so were the persons of the women, who were walking to and fro, laughing and chatting very sociably together. Others were sewing and quilting in rooms set apart for that purpose. There was no appearance of wretchedness or misery in this ward; nothing that associated with it the terrible idea of madness I had been wont to entertain—for these poor creatures looked healthy and cheerful, nay, almost happy, as if they had given the world and all its cares the go-by.

For all its light, however, the place was not all sweetness. The administration of the facility continued to be marked with political favouritism in the employing of staff and a not-always-benign neglect of the patient residents. The chairman of the board and the hospital superintendent engaged in constant in-fighting.

Early in 1853 a grand jury was called in to investigate. Its members avoided involved medical or administrative controversies, focusing their interest instead almost exclusively on the building and physical arrangements. They found the rooms “uniformly clean, in good order, comfortably warm, and with one or two exceptions properly ventilated.” In their opinion, the kitchen was “well managed,” and the food “of the best description.” The patients were “clean,” “well behaved,” and during the whole of the jury’s three-hour visit, “not one obscene or profane word reached the ears.” The jurors thought “the treatment of the patients appeared to be mild and indulgent, the persons in charge of the wards attentive; and with the more violent cases even forbearing towards the unfortunate persons whom it was their duty to watch over.” The grand jury made a number of minor suggestions about such matters as ventilation and plumbing, noting that there did seem to be a drainage problem, but “no offensive smell could be detected in consequence”

The stink of politics, however, persisted. A second grand jury also visited the asylum. Its members found “every portion of the building … well ventilated, and free of all unpleasant smells,” but they did note the need for a few physical repairs. These jurors also showed an interest in godliness as well as cleanliness by commenting that they “in no instance heard an improper expression.” While jurors could not claim to be “good judges of how such an establishment should be regulated,” they commended the administration: “We feel bound to say that, in our opinion, their treatment pursued towards the unhappy insane of the Asylum is humane, kind and attentive.”

Despite such uncritical reassurances, controversy continued. By July, 1853, a new “Act for the Better Management of the Provincial Lunatic Asylum at Toronto” went into effect and the medical director resigned.

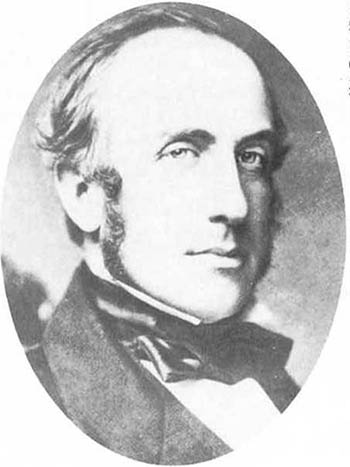

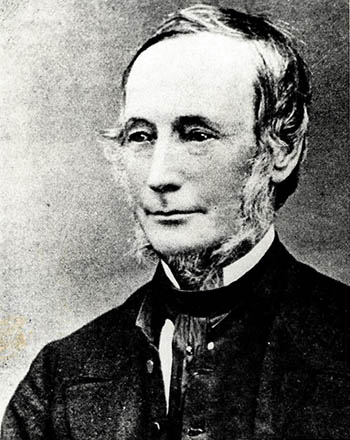

Into the troubled place, Joseph Workman stepped, armed by the provisions of the new act with the powers required to clean up the place. Workman was no stranger to political conflict. A native of Northern Ireland, he studied medicine at McGill in Montreal, taking a particular interest in the Asiatic cholera epidemic which was then plaguing Canada. He received his medical degree in 1835, but the next year moved to Toronto to take over a struggling family hardware business. In Toronto he soon plunged into city politics as a champion of the Reform cause. Ten years later, he returned to his first love, medicine, built up a large practice, and began teaching at the Toronto School of Medicine, specializing in midwifery and diseases of women and children. He also continued his political activity, was elected as a city alderman, was appointed to a three-man committee to inquire into the affairs of King’s College, and was elected chair of the first Toronto Public School Board. He also found time to assist in the establishment of a Unitarian Church.

During this time Workman often wrote his opinions to the press, and for a time he edited the Toronto Mirror, one of the Globe’s fiercest competitors. It was during this period that Workman’s antipathy toward George Brown (and Brown’s toward Workman) probably developed. By 1852 Workman was referring to Brown as “an unprincipled editor … an enemy with whom the public should do battle”

Upon his appointment to direct the asylum, Workman immediately set about cleaning and ordering the physical facility. His knowledge of hardware—especially plumbing—no doubt came in handy. There were problems with flues, problems with vents, problems with windows, problems with the water supply, and especially problems with drains:

Every apartment abounded with foul air; and it was found beneath the basement floors, covering a space of six hundred feet in length by thirty to one hundred feet in breadth, there had … accumulated a mass of filth and impure fluids, the stench from which, when first exposed, was so insufferable and overpowering, as instantly to sicken several of those … who chanced to inhale it … Beneath the kitchens and adjoining parts, the filth was found to measure from three to five feet in depth; and was of varying consistence, from that of dense mud to thin molasses. The superjacent floors and joists were so rotten as to yield under every passing foot, and in several places had given way, leaving openings from which issued the most offensive effluvia. A rank fungous vegetation hung from the under surface of the decayed timbers. The dry-rot had seized the wood skirtings … and extended into the upper stories.

The new superintendent also found himself faced with a very different type of problem to clean up:

An evil of inconceivable magnitude … in the working and present condition of this Institution has been the introduction into it, of criminal Lunatics from the Provincial Penitentiary, and the County Jails. It is an outrage against public benevolence, and an indignity to human affliction, to cast into the same house of refuge with the harmless, feeble, kind-hearted and truthful victims of ordinary insanity, those moral monsters … or, yet worse, those villains who affect insanity by means of evading the just punishment of the most atrocious crimes.

Workman believed that for his patients to benefit from being under his care, both the physical and the spiritual environment had to be unpolluted. Surprisingly, perhaps, he believed in making as little use of medicine as possible. When it was necessary, it was to be “administered for the relief of bodily ailments and not for the cure of the mental malady.”

Paradoxically, perhaps, Workman was aware that his asylum was not necessarily a therapeutic place for all sufferers. There were many cases of “unreal or ephemeral lunacy” which, he believed, were better refused admission, “many of which might, by dragging the poor creatures to Toronto, and incarcerating them amongst the dense crowd of maniacs in our house be transformed into cases of real madness.” He believed that “50 per-cent of the alleged cases of lunacy for which admission into the asylum is sought are curable at home, under appropriate treatment.”

Such a stance was politically unpopular. Almost as soon as the Provincial Lunatic Asylum had opened its doors, local officials began to recognize its utility as a boarding house for unmanageable persons, whether or not they were actually mad. As one modern historian describes it, authorities sent “all variety of misfits and trouble-makers, their indigent, their congenitally defect, and their old and senile.” Most of these may have been harmless, but most were also incurable, taking up space needed for those who were, in Workman’s words, “acute, improvable or truly dangerous.” The superintendent tried to maintain strict admission standards, but it was not easy, and in time the institution became more and more crowded.

In consequence, Workman was constantly lobbying for funds to allow the completion of his half-finished building. The intransigence and stupidity of the Legislature, he believed, was preventing him from doing his job. A few weeks before the libel trial, he poured out his frustration to a Member of Parliament:

If we had a single man in the Legislature who had ever studied the subject of insanity & insane Hospitals, before today this house would have been completed. What sort of an account can any of you give at the bar of Heaven, for your willful ignorance, and woeful negligence? “Depart from me, ye cursed.”

Although this was a private communication, such hostile feelings can hardly have helped Workman in his public efforts to gain approval and assistance for his asylum.

Workman could be equally harsh in reproaching his fellow physicians. “Nothing,” he once wrote, “has so largely contributed to the filling of this asylum with incurables, as the almost astonishing ignorance of the medical profession, on the true nature, & the proper treatment of insanity.” One of his reports attacked the maltreatment of the mentally ill with “active and depressing therapeutic measures,” including, “bloodletting, purging, vomiting, salivation, blistering, cupping, setons, low diet, and the whole battery of medical destructives.”

He scoffed at most of the presumed causes of mental illness, “in nineteen cases out of every twenty, entirely fallacious.” Among the extraordinary causes listed by relatives or medical examiners were:

Grief; Love; Loss of Property; Religious Excitement; Religious Despair; Family Quarrels; Jealousy; Fright; Disappointed Affections; Excessive Study; Reading and Fasting; Intemperance; Breach of Promise of Marriage; Suppression of Menses; Slander; Want of Employment; Marriage; Miscarriage, and bad treatment; Spirit Rapping; Death of Child; Death of Husband; Death of Wife; Business Difficulties; Political Excitement; Disputed Boundary; Strong Tea; Eclipse of the Sun; Religious Controversy; Inhalation of Nitrous Oxide Gas; Reading Religious Books; Tobacco; Remorse of Conscience, &c., &c.

If any one of these, Workman asked “may be regarded as adequate to the overthrow of reason, how many lunatics should this Province contain? Intemperance alone would people fifty Asylums as large as our present one. Jealous wives and husbands would probably fill thirty.” “Political excitement,” he continued, “would tenant a mad-house in every county, and one of superior class and size in the metropolis.” While “religious controversy would send in half the clergy of this Province, and large detachments of their congregations.” If “tobacco and slander” caused insanity, there would be few in Canada left “at large.” Such scathing judgments were perhaps the source of some of the enmity against him.

On the other hand, Workman was clear about what he thought were the real causes of madness, such agencies as:

Gestation; Puerperal disorder; Over lactation; Fevers resulting in cerebral lesion; Sun-stroke; Intense cold to the head; Injuries of the skull; Apoplexy; Epilepsy; Parental intemperance; Masturbation; Scrofulous and syphilitic taint; Defective diet.

Nonetheless, for all such largely physical causes, Workman believed there was something more: “Underlying or interwoven with these, or other efficient causes of insanity, are to be detected evils in the existing state of society, and it is to be feared in the pernicious tendencies of modern education and the moral training of youth.”

In one annual report, Workman quoted one of his colleagues, the director of an American asylum, who reported the case of one poor patient:

The hair becomes dry and falls off; the eye becomes vacant and watery, and the lids are red and tumid; the countenance is pale and expressionless, the flesh wastes, the limbs hang loosely to the trunk, the muscles are flaccid, the skin loose and scurfy, the hands are purple and cold, and the palms exude a constant viscid sweat. Long periods of utter inaction are sometimes suddenly broken by spells of uncontrollable fury, spending themselves on the nearest object within reach. Finally the wretched object becomes motionless and inert. He rises and sits down, eats and sleeps, only as he is prompted to such acts by others.

There was no doubt in Workman’s mind that some unknown “secret evil” lay behind all this, causing such awful behavior:

The corrupt family servant, the vicious school-fellow, the libidinous book or picture, or simply the unchecked work of a wanton imagination, has sown the small but fatal seed of ruin—has broken down the golden wall of youthful purity and let in vice in one of its most loathsome and destructive forms.

Here, no doubt, was the reason why Workman was so shaken by the supposed revelations printed in the Toronto Globe. They were not simply accusations of a faulty asylum administration. They brought into question the environment of virtue which he believed was essential to his institution.

Caring for the mentally ill was, to him, not merely a matter of medical therapy, it demanded moral management.

The libel case of Workman v. Brown held in the York County courthouse on 22 and 23 April, 1857, created something of a public sensation. Nearly all the Toronto newspapers gave it extensive coverage. Former asylum porter James Magar’s accusations were examined in detail. Two of them were perhaps titillating, but hardly shocking, save that they suggested an unacceptable permissiveness at the asylum:

First … that the female lunatic patients were exposed to improper intercourse by the Steward … who allowed Thomas Pearce, a patient … formerly a convict in the Penitentiary, to go at his pleasure through the female wards to examine whether the windows required glazing, until he was detected by … a nurse … with a female in a private room … Report No. 2. That the Steward did not pay proper attention to the security of the Government property in allowing (the same) Thomas Pearce … to take one of the horses and go for whiskey … and … with a horse and cart that he might get through the gates for sugar sticks.

A parade of witness were called to testify, many of them former employees who had reasons to be hostile toward Workman. Little was actually proved, however, although spectators at the trial were treated to testimony by Pearce himself. Amidst laughter, he tenaciously stuck to his explanation that he had been fixing the pipes when he had been discovered in the women’s ward bath room, in the dark, at eleven at night. It was, however, never ascertained whether a woman had in fact also been in there with him.

A third accusation made by Magar was obviously far more damaging:

A female in one of wards was in the family way, and when she took labour and her pains increased her madness, the nurses did not know, and put on her a straight jacket, and confined her in the common place of punishment, when it was discovered by the cries of the infant, without Dr. Workman ever having told the attendants of her having been pregnant; the sight of the mother was awful, her face was all covered with blood in endeavouring to extricate herself.

Once more there was a parade of witnesses—nurses, attendants, doctors, hospital commissioners—who, while denying that the patient had been put in a strait jacket or had been put in a confined space for punishment, confirmed that a birth had taken place. They also confirmed how constantly dirty and distraught the patient had been. Professional medical witnesses disagreed, however, as to whether such an surprise birth was evidence that the patient had been improperly treated, either by Workman or by others on his staff. (The child, by the way, was baptized—with Workman as godfather—but it lived only a few days.)

Scandalous as these accusations were, they were not exactly new. When they had first been brought to Workman’s attention, he immediately called for an official investigation by the Visiting Commissioners of the asylum. They quickly made a full inquiry, took statements, examined witnesses (including Magar) and unanimously concluded that the charges “were utterly without foundation and completely void of truth.”

Although their report had been immediately forwarded to provincial authorities and had been printed on 5 March, George Brown had refused to publish the report in the Globe, thus allowing Magar’s charges to stand unanswered.

All this might be juicy scandal to the ordinary reader, but there was more, fed perhaps by old underlying political hostilities. Trial testimony brought out two damaging facts, albeit not specifically relevant to the libel suit.

For at least two years there had been a fierce feud between Workman and his bursar—the two rarely spoke. Also, the former assistant superintendent had recently been forced out, the post being filled by Workman’s brother, Dr. Benjamin Workman. Such evidence can hardly have helped the Medical Superintendent’s case.

Despite its name, Provincial Lunatic Asylum, the hospital was not a safe place separate from the world. Its creation and its administration were inevitably involved in the political machinations of the time. Since it spent public money—a great deal of public money—it was always subject to public scrutiny, especially by journalist/politicians like George Brown.

Since it hired many public employees, it was ever subject to accusations of patronage—in those days patronage politics touched every provincially administered institution. Brown had taken an interest in it long before it opened. He had opposed Workman’s appointment—itself a patronage gift from Dr. John Rolph, then an influential member of the provincial government.

Once he became asylum director, however, Workman saw his sole responsibility to be his patients. He did not do enough to curry the favour of those, like Brown, who were in positions of influence. “My politics,” he wrote but two years after taking office, “are lunatic asylums.” Only a few weeks before the trial, he revealed his hostility to the press in a private note to the editor of another paper:

I solemnly declare that my duties amongst my patients are to me a source of happiness beyond all sublunary enjoyments. I love my patients—and they love me—they are honest, truthful, grateful. I detest the world outside these walls. You had rather be an editor. I had rather restore reason. You rejoice in the function of distracting it. God help the world!

Why had Workman, instead of going to court, not written a response to the Globe refuting the scurrilous charges? Because he carried an old grudge. Three years earlier there had been a dispute about the Toronto School of Medicine.

“Brown then lied with perfect knowledge of the sin,” declared the righteous Workman to the father of one of his patients. On that occasion, the Globe editor had steadfastly refused to print the doctor’s refutation. He was not about to try that course again.

Workman’s lawyer argued that Brown had published the reports “to gratify a vindictive and malicious spirit.” Had he, Brown, taken the trouble to visit the Lunatic Asylum, he would have found it in perfect order.

The lawyer pointed to a conspiracy against Workman, implying that Brown was part of it, out to use “the evidence of discarded and degraded menials to crash a man.” The institution’s recent history was well known, each of its four previous superintendents had been “subjected to every kind of libel slander” so each “had been driven from the Institution.”

The trial ended with the jury unable to reach a decision. The Globe reported that only two of the twelve jurors had favoured damages for Workman while nine had sided with Brown—apparently they believed that at least some of the accusations against the asylum were true.

Workman weathered the storm—he did not resign his post. He went on to serve as Medical Superintendent for more than two decades, retiring in 1875—“for reasons understood by myself” he recorded in his diary.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.