Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

Urban Homesteading

The cheese stands alone, the cheese stands alone, hi-ho the dairy-o, the cheese stands alone!

It does, but it’s also pretty good with roasted beets.

“It” is chèvre, made by yours truly in a six-hundred-square-foot apartment in downtown Vancouver with nothing but basic kitchen equipment and four litres of Fraser Valley goat’s milk. Now I’m now on the hunt for Penicillium candidum and real cheesecloth: it’s Camembert by Christmas!

As it turns out, my cheese-making adventures aren’t so unusual. In fact, I’m part of a sociological trend. (Don’t you hate it when that happens?) Urban homesteading is a twenty-first-century social movement promoting self-sufficiency in the name of sustainable living. Among other things, an urban homestead produces its own food, is powered by alternative energy sources, recycles grey water, and collects rainwater.

Urban homesteaders try to recreate a local economy as much as possible, working from their homes and trading goods and services with their neighbours. They’re the people with mason bees and chicken coops in their backyards — the annoying ones who brag about making cheese.

What’s the appeal here? After all, I grew up in a self-consciously modern household: We were raised by non-hippie parents according to Dr. Spock and with the “helping hands at Kraft,” surrounded by Scandinavian design furniture. Orange was the colour of my youth.

No, my journey from Kraft to craft — from Cheez Whiz to artisanal cheese — came as an adult. Like many, I find urban homesteading appealing because it hearkens back to a world we seem to have lost, a time that seems simpler and slower. In the process of making bread or planting a garden, there’s space for other things to grow — like an understanding of how the natural world works and the limits of our control over it.

Acquiring a competency is enormously satisfying, all the more because the self-sufficiency it makes possible is one that’s rooted in relationships. It’s called DIY, but the doing is often the result of conversations with other DIY-ers. Preserving food or planting fruit trees connects you to a community of like-minded people, and that has great appeal in the fast-paced, fragmented, and anonymous world in which we live, a world where cash is the connective tissue of society.

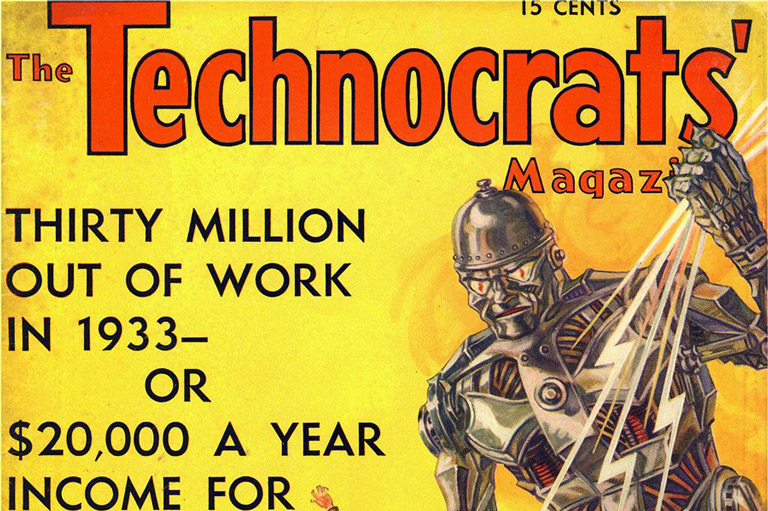

But urban homesteading isn’t just a sociological phenomenon, it’s a historical one dating back well beyond the 1960s. In the late nineteenth century, many among the privileged urban classes in Canada, the United States, and Great Britain reacted against the very forces that made modern life modern: mechanization, industrialization, and urbanization — in short, all the developments that are commonly thought of as progress.

It wasn’t so much that they were against progress as that they were struggling with the unprecedented changes progress brought and the speed with which it brought them. While it was exhilarating to see “all that was solid melt into air” — to use Marshall Berman’s evocative description of modernity — it was also frightening. What was the world becoming? What were we becoming?

These worries coalesced into a loose critique of progress that historians have dubbed “anti-modernism.” It was characterized by nostalgia, a sense that there was something lacking in the present that could be found in the past. Anti-modernism sparked a growing interest in medieval and Eastern cultures; it lay behind the Arts and Crafts movement.

Closer to home, it inspired an interest in Atlantic Canadian folk cultures and pushed millions outdoors to “get away from it all” by cottaging in the Muskokas and Laurentians or, if you really had money, at St. Andrews-by-the-Sea and the Lower St. Lawrence.

In the West, many people took up Teddy Roosevelt’s call for the “strenuous life” — hunting, fishing, and hiking in the Rockies. Anti-moderns believed intense experiences could penetrate the artificiality of modern life, leading to a purer, more meaningful, authentic existence.

A century later, we seem to be suffering from another bout of anti-modernist flu, and once again we’ve turned to an imagined past to cure what ails us. Most of us live urban lives that are astonishingly dependent on miraculous electronic technologies that have shrunk the world far more than those who marvelled at the railway could ever have imagined.

And yet, like our forebears, we’re ambivalent — not, perhaps, about industrialization but about what globalization has wrought: a world of interconnection and loneliness, of standardization but not safety; one where neither time nor space are barriers. The same society where you can buy mangoes all year round is also one where people find themselves wanting experiences that are bounded and grounded — that are “real.”

Urban homesteading is only the latest manifestation of anti-modernism and the search for authenticity, for real connections with the people and things in our lives. Our disenchantment with a globalized world explains why we love knowing where the food we eat comes from, how it’s grown, and who grows it; it’s partly what’s behind the appeal of craft beer and artisanal bread.

What we want is what French winemakers have known and marketed so well as terroir, the unique qualities that come from the soil and environment in which things are grown. For something to be “authentic” it has above all to be rooted in place, put there by hand — ones attached to a real person making a real living from the land.

Like cottaging and the wilderness craze, urban homesteading emerged from an important critique of how the world we live in is wanting. And like those earlier instances of anti-modernism, the critique that gave urban homesteading its life has morphed all too easily into elitist consumerism and conservatism.

Instead of getting political and challenging the system that created the problems they railed against, people turned inward. They read Helen Creighton’s collections of Nova Scotia folktales and heritage seed catalogues. And they went shopping — for hooked rugs, cottages, and, most recently, authentic experiences in the backyard, kitchen, and community garden — the new urban frontiers.

Sign up for any of our newsletters and be eligible to win one of many book prizes available.

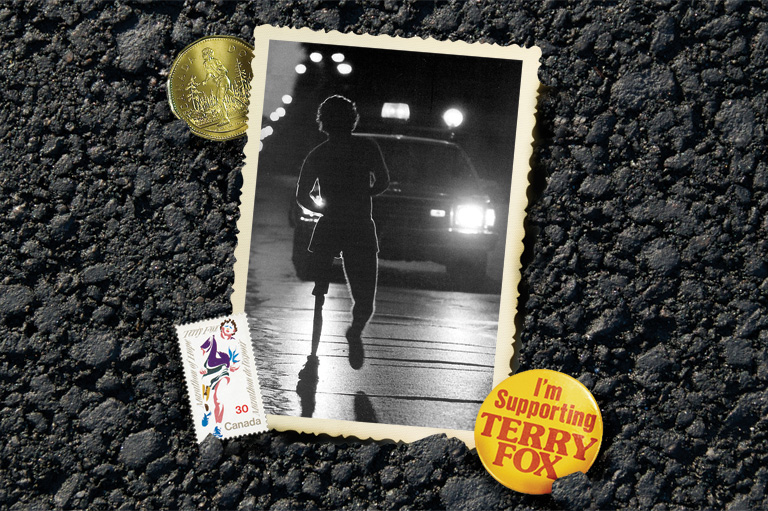

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!