The Language of Métis Folk Houses

Seven years ago when Ron Bazylak bought his house at 216 First Street in Duck Lake, Saskatchewan, he had no idea what he was getting into. As a youngster he used to deliver groceries to the old veteran who lived there, but he knew nothing of the home’s place in Canadian history until he tried to pull a spike out of the living-room wall.

“We used nail pullers and crowbars but it stayed put,” he recalls. No wonder. Under the yellow siding are solid logs, hand-hewn by veterans of the 1885 Riel Rebellion whose first shots were fired near here.

Bazylak’s place is one of just two remaining Métis folk houses still inhabited. These log residences of the St. Laurent de Grandin district on the South Saskatchewan River are different from other log dwellings now crumbling into the prairie.

Their exteriors are decidedly Georgian, with medium-pitched gable roofs and central doors with perfectly balanced window placements. But once you walk inside, they are decidedly non-Georgian: open communal space just like the Plains Indian tepee.

This combination of features is no mere happenstance. As Simon Fraser University archaeology professor David Burley writes in the journal Historic Archaeology, the Métis integrated elements of several different cultural backgrounds. English, French, Scottish, Cree, Ojibwa, and Assiniboine were brought together by a creolizing process and bonded by a unique language, derived from French and Plains Cree, known as Michif.

Just as the Michif grammar bound together their founding lexicons, so the Métis folk house bound together components of their founding cultures.

The Métis culture was forged in the western Canadian fur trade. By the mid-nineteenth century, it had evolved into an ethnically distinct and recognizable group replete with lineaments like its own architecture and trademark stone-tool butchering techniques. In addition to their fur trading, the Métis during the first half of the 1800s took part in communal bison hunts in the Red and Assiniboine River areas of Manitoba.

But as settlers and homesteaders encroached upon the diminishing herds after 1860, many Métis were forced to abandon the hunts and move further west. By 1880 they were a culture and society in transition from being hunters to being farmers, and many resettled in the Saskatchewan parkland.

One of the areas where they put down roots was the pleasantly wooded parish of St. Laurent de Grandin on the South Saskatchewan River, ninety kilometres north of present-day Saskatoon. Here they built their farms and villages, the best known of which is Batoche, a town that became the centre of the Métis rebellion of 1885.

They built using an architectural style that was not only unique in Canada but a departure from the Red River frame style they fell behind. Scholars have dubbed it the St. Laurent style.

The St. Laurent folk houses, built from the 1870s to about 1940, varied only slightly from one another. Most were one-and-a-half to two storeys high with a medium-pitched gable roof.

Other defining characteristics include an open interior floor plan, the only room division being a shed-roof lean-to added off centre to the back façade or the end wall, which was built alter initial construction and used for a summer kitchen or for storage.

A simple staircase up to the sleeping area was always placed against one wall. Iron stoves instead of fireplaces were used for heating, and a root cellar was centralized beneath the floor.

As with most of the earliest prairie settlers, the Métis expertly adapted local materials. Naturally flat stones were hauled from the river for foundations. Construction was of locally available white poplar, black poplar, tamarack, or spruce logs, squared or hewn and secured at the corners using tight-fitting dovetail joints.

“The dovetail was faster and more solid than the Red River style,” explains Métis elder Ed Bruce. (The traditional Red River style generally employed tenon-and-groove construction — where squared horizontal logs are cut to fit into grooves in a vertical log.)

Using solid, long-lasting construction methods was also one mark of a more permanent lifestyle. Bruce says wall logs were frequently strengthened with dowelling placed vertically within the logs. A later feature was wattle-and-daub-covered exterior walls: local plasters and clays held in place by willow-branch lathing, a style thought to have been influenced by Ukrainian builders immigrating to the area in the early 1900s. Roofs were of locally made wooden shingles.

A most striking aspect — one that distinguishes the St. Laurent style from other log residences — was the front façade.A characteristically central door was balanced by window placements to either side.

“The symmetry with which the façade is executed provides a Georgian-like architectural appearance that seems abruptly foreign to a recently transformed buffalo-hunting people,” writes Burley, who conducted a survey and cataloguing of the folk houses in 1986.

Other scholars trace the feature’s origin to the United Empire Loyalists who applied Georgian principles of symmetry: after 1870, eastern Canadian migration to this area had intensified.

Inside, one sees the other feature that sets the Métis folk house apart from other prairie settler’s abodes — the open floor plan. Burley relates this to a unique aspect of Métis culture: their world-view.

Data he collected showed the Métis to have “an organic, informal, unbounded and open society with strong continuity in the human/nature relationship.”

He writes that, even after the dramatic transition in Métis economy from communal hunter to settled farmer, the structuring principles of this world-view continued to affect the Métis response to land, material goods, spatial organization, and social relations.

“When one entered the South Saskatchewan River house, one did not confront doors, formality or privacy, but came upon the range of activities incorporated within the Métis domestic sphere.” he writes. “The interior of the house is commensurate with a lack of boundedness ... an environment in which Métis sense of communalism, consensualism and equity were pre-eminent.”

This meant that the main area served all of these functions: cooking, dining, and socializing. When later lean-tos were added, these patterns sometimes changed slightly. Small additions on the back became the kitchens, leaving the entire main room for sitting and entertaining.

The second floor, reached by the end-wall stairs, was always for sleeping. Overnight guests generally slept on the main floor.

Burley compares the various cultural features integrated into the buildings with the Michif language:

“These components correspond to the lexicon of Michif,” he writes. “They are the ‘words’ from which the house type has been built ... and the rule system that binds the building components together is the grammar.”

The folk houses dotted the valley for decades until the early 1930s, when increased communication with the outside world invaded local culture. Autos, electricity, and radios began to change life in St. Laurent parish. Along with them came the availability of sawmill lumber, and craftsmen gradually abandoned the labour-intensive dovetail joinery, turning instead to frame housing.

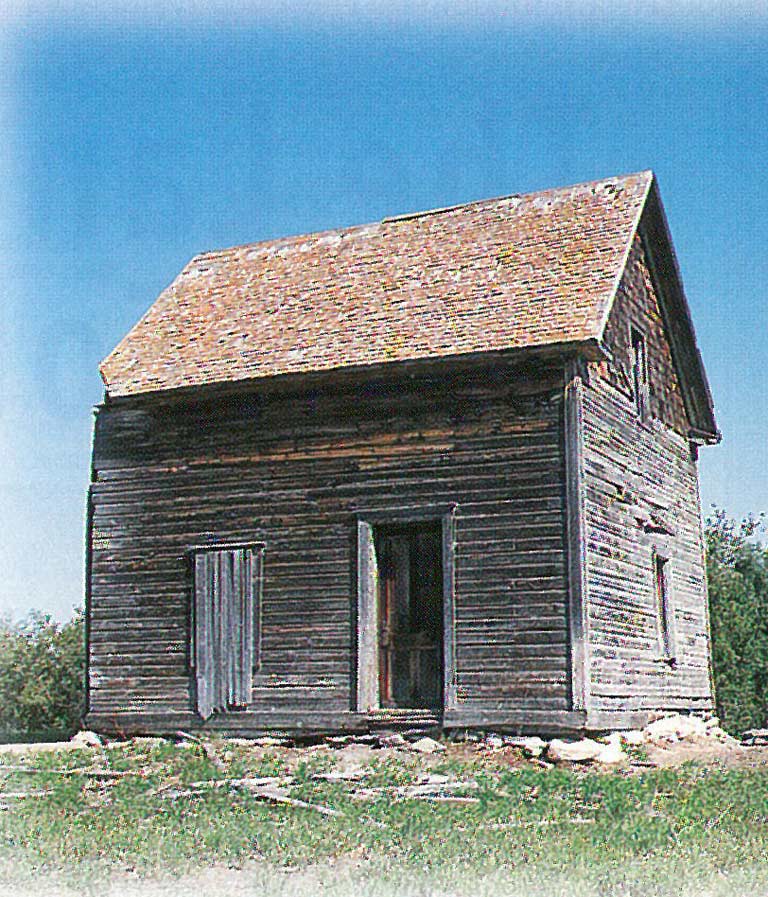

Burley’s team recorded a total of twenty-four St. Laurent-style folk houses built between 1882 and 1940 still standing; today only eight remain. Six of these sit forlornly in fields, interiors gutted or filled with hay, desolate reminders of Saskatchewan’s rich Métis heritage.

One has been preserved at the Batoche National Historic Site and the other, Ron Bazylak’s still has the spike in its wall.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.