Remembrance

In 1931, an act of Canada’s Parliament changed the name of Armistice Day to Remembrance Day. There were many motives behind the legislation, but of particular concern was that Armistice Day was too closely connected to a single historical event – the 1918 cease-fire that brought the fighting on the Western Front to an end.

When it was first observed, Armistice Day had been about victory (the legislation referred specifically to the day “on which the Great War was triumphantly concluded”); but a decade later Canadians no longer had the same need to celebrate the moment that the Germans had thrown in the towel.

Much more suited to the time was the name Remembrance Day, which was directed at a general spirit of commemoration. It would encourage people to contemplate not just one day but the values that animated Canada’s war effort — democracy, freedom, justice, Christianity — and the fact that more than 60,000 Canadians gave their lives to defend those values.

But there was no assumption that Remembrance Day would embrace past wars, whatever values they had been fought to preserve. The legislation mentioned only the dead of the First World War. That it should also be an occasion to commemorate the 250 men who died in the South African War or the 9,000 men who died defending Canada against American invasion in the War of 1812 was never considered.

And, although politicians couldn’t know that within a decade the country would be involved in its second world war in a generation, they were not naive enough to imagine that the Great War would also be the last war. After all, it had been known as the “war to end war” (not the “war to end all wars,” as it is often misquoted today); it was part of a long campaign to stop war, but it was not necessarily the final act.

When the next war began in 1939, it became a matched set with its predecessor. They were the first and the second, the war of the fathers and the war of the sons, the Great War and the “good war.” If few Canadians subscribed to the notion that the world wars actually constituted a single long conflict separated by a twenty-year pause, they did accept that the two were inextricably linked.

And so it was obvious that the Second World War would be commemorated alongside the first, but when should that commemoration take place?

A committee of British and Dominion representatives discussed the matter in 1945, but all of the proposed alternatives were found wanting. The sixth of June was a favourite in Britain and Canada, in part because it offered better weather than November, but the Normandy invasion had little resonance in Australia and New Zealand.

The declaration of war in 1939 was discussed, but it occurred on different days in different countries — and was it appropriate to commemorate the war on the anniversary of its outbreak? VE Day on May 8 had been an occasion to celebrate the surrender of Nazi Germany, but it wasn’t suitable because the war had continued in the Pacific for another three months.

VJ Day, which brought that war to a close, never had the same emotional resonance, because it was connected to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and because the term was commonly applied to three different days. One by one, all of the alternatives were dismissed, and the committee eventually concluded that the dead of the Second World War would continue to be commemorated, as had been the practice since 1939, on the anniversary of the day the First World War had ended.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The decision affirmed not only that the wars were connected but that they were distinct. They could be placed within a continuum of Canadian history, but the collective memory accepted that they were unique.

It was a popular device amongst historians, journalists, artists, and poets to compare the Canadian infantryman of the twentieth century to the habitant-turned-soldier of the eighteenth century and the militiaman of the nineteenth century, but the first and second world wars were of an entirely different order than anything which had come before. They enjoyed a privileged position in Canada’s collective memory, for there were only two kinds of conflict in Canadian history: the world wars, and everything else.

That’s not to say that earlier conflicts failed to stir the commemorative impulse. As late as 1949, veterans of Toronto’s 10th Royal Grenadiers who had served in the North-West Rebellion continued to hold reunions, where they drank a toast to departed comrades: “So here’s to the Army, the Navy, and the Queen, for we have done our duty, boys, wherever we have been, when out on Active Service, we made the rebels flee, we have the good old British pluck in the 10th R.G.”

Before Armistice Day even existed, there was Paardeberg Day, celebrated every year on the anniversary of the Royal Canadian Regiment’s victory over the Boers in 1900, and Trafalgar Day, which marked the great British naval victory over the French in 1805. Both were observed in Canada well into the twentieth century, and are observed to this day in some quarters.

In 1927, Alberta teacher and historian W. Everard Edmonds published The Canadian Flag Day Book, with the suggestion that teachers observe two flag days each month as a way to inculcate in their students the spirit of patriotism.

Although the author claimed there was no militaristic intent in the suggestion — the exercises were to teach young people “that bravery may be shown each day on life’s battlefield,” he wrote in the introduction — the days did lean rather heavily towards the martial past: the anniversaries of the institution of the Victoria Cross (1856), the Battle of St. Julien (1915), the declaration of war in 1914, the Battle of the Plains of Abraham (1759), the Battle of Trafalgar, the Battle of Queenston Heights (1812), and the Armistice of 1918.

Almost every conflict was memorialized in bronze and stone. Generals Wolfe and Montcalm, on opposite sides of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, share a monument in Quebec City, unveiled in 1828 and graced by a fine inscription: “Military virtue gave them a common death, history a common fame, posterity a common monument.”

There is Brock’s Monument in Queenston, Ontario, the second version of which has loomed over the Niagara River since 1859 on the site where the defender of Upper Canada was killed in action. Halifax boasts the splendid Welsford-Parker Monument, dedicated in 1860 to honour the British victory in the Crimean War and the Nova Scotians who died in the fighting there. In 1870, a dignified column was erected in Toronto to commemorate nine young men from the city who died defending Upper Canada against the Fenians.

The Boer War produced some of Canada’s most striking war memorials — George Hill’s wonderful dismounted soldier in Montreal’s Dorchester Square; Calgary’s exceptional equestrian statue; memorials to individual soldiers in Canning, Nova Scotia, Cayuga, Ontario, and Granby, Quebec; and a host of other bronze figures in Canadian cities. Clearly, the desire to commemorate and pay tribute to the nation’s military dead was not just a product of the first and second world wars.

What elevated that desire to a different level was the scale of the world wars. By any measure, they were bigger, more far-reaching, and more influential than any conflict, before or since, in which Canadians have been involved. While the overused phrase “total war” is hardly applicable to Canada at any time, the world wars did touch all parts of the country, all ranks of society, all aspects of life. They were on street corners as propaganda posters and newspaper headlines, and in music halls and cinemas.

Children learned about them in school and then descended on their neighbourhoods to collect pennies for war charities or scrap to be turned into munitions. Conflict dominated popular music and filled the pages of Canada’s magazines.

Bubble gum and cigarette cards, sermons and radio broadcasts, cookbooks and greeting cards — virtually everything took on military overtones. And there were uniforms everywhere. Only at the most isolated farm or logging camp would it have been possible to imagine, even for a short while, that there wasn’t a war on.

No conflict before or since had such reach — and this is not to denigrate the sacrifices of the men and women who served in them. But the Boer War or the Korean War simply weren’t pervasive or transformational like the world wars, which brought profound change to Canada in ways that have still not been fully understood. The First World War brought smothering collective grief but also a powerful sense of national feeling (and a new stature on the world stage) that had not existed a few years earlier — not to mention women’s suffrage, daylight savings time, and income tax.

In the 1920s, it became a truism to insist that more change was witnessed (in aviation, medicine, manufacturing — insert area here) through four years of war than in fifty years of peace. The Second World War remade Canada, in the space of just six years, from a country broken and demoralized by a devastating economic depression to one of the wealthiest, most powerful nations in the world. And if Canada’s time as a legitimate superpower was short-lived, postwar prosperity, big government, the social welfare state, and a dozen other things affirmed that the Canada of the 1950s bore little resemblance to the Canada of the 1930s.

But are those facts reason enough to set aside for the world wars an annual day of commemoration? Other events have brought profound change, albeit not in such an intense, concentrated fashion — and yet they don’t have a mandated day of remembrance.

The only occasion that does is Canada Day (as Dominion Day was renamed in 1982); but it, like Remembrance Day, has long since ceased to focus on a single day in history and instead is directed at celebrating the nation in a more general sense. Nothing else in Canada’s collective memory is as commemorated as the world wars, a fact that, since the 1930s, has been a bit of a sore point in some quarters.

Decoration Day, first observed in Toronto in 1890 at the urging of veterans who had fought the Fenians thirty years earlier and given new life in the 1920s through ceremonies to place flowers on the graves of Great War veterans, had a strong following in parts of Canada; the tradition of decorating the graves of heroes of peace was little more than a fringe activity.

Even then, some of the official participants were decidedly ambivalent. Archdeacon J.C. Davidson, a former military chaplain, was happy to take part in Toronto’s 1930 ceremony to decorate the graves of heroes of peace, but felt the need to remind his audience that “this ceremony does not in the smallest degree detract from the honour which we all so gladly give to the soldiers of the Empire.”

Remembrance Day in the interwar era attracted vast crowds in virtually every city in Canada, while Peace Day parades usually drew just a handful of curious onlookers. “Heroes of peace seldom get the recognition they deserve,” observed the Victoria Times in 1936. “They may display a selfless devotion which, if shown in war, would bring them the thanks of their country, without getting so much as a passing nod from their fellow citizens whom they are serving.”

Dying for a good cause in wartime merits an annual day; dying for a good cause in peacetime doesn’t. Critics have long argued that this is misguided. In their view, to remember war is to celebrate war.

This, of course, is utter nonsense.

By the same logic, to mark the anniversary of the 1989 Montreal Massacre, when fourteen women were murdered by a gunman at École Polytechnique, is to celebrate violence against women. One observes the anniversary of an appalling tragedy because one hopes to have some impact, however minuscule, in preventing it from happening again, and out of a belief that the dead deserve something better than to be consigned to historical oblivion.

Commemoration of the world wars has always been about that desire to preserve the fallen in the collective memory.

A war memorial was first and foremost a memory aid, a role that is no less important today. As personal commemorations like maintaining a vigil on the Highway of Heroes mix with the kind of virtual commemoration permitted by Facebook and Pinterest, there is more need than ever to anchor these transitory practices on a tangible memorial that occupies a public space. Granite and bronze serve that critical purpose today, just as it did a century ago.

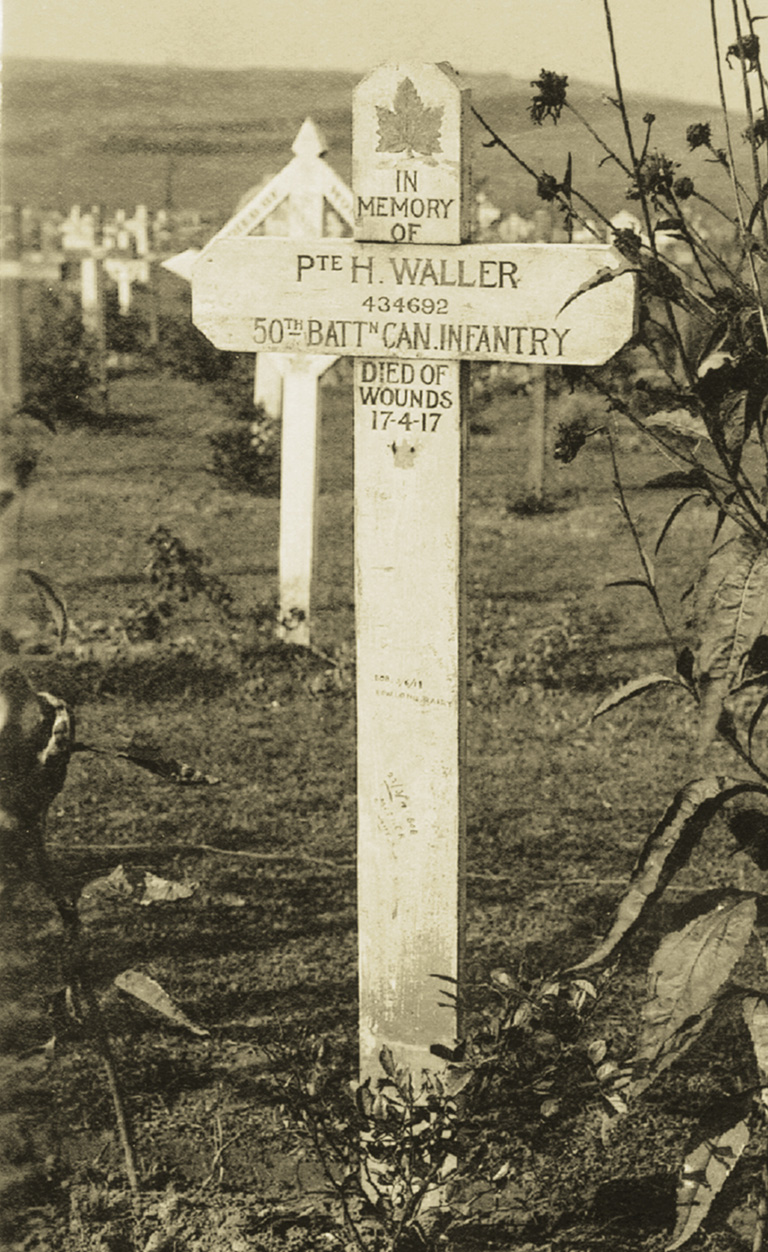

For the generation of 1914, the immediacy and intensity of the loss made the need to remember that much more pressing. The war memorial was also intended to be a substitute grave for loved ones who would never be able to visit an actual grave or, in the case of the missing, had no grave to visit — the word “cenotaph,” after all, literally means “empty tomb.”

Where there is a grave, the thinking went, there can be no forgetting. Similarly, Remembrance Day is, in essence, a national funeral in which the nation re-enacts the burials of the dead so grieving relatives can experience the funeral that was held a continent away, if at all. Where there is an annual funeral, there can be no forgetting.

We are entering a period of unprecedented commemorative activity with the one hundredth anniversary of the First World War and the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Second World War.

There will be criticism — that a triumphalist, nation-building narrative is being privileged for political reasons, and that the obsessive commemoration of all things military is an effort to use the past to legitimize a certain agenda in the present. There is a certain element of truth to the charge.

Every act of commemoration is political, because the act of remembering is itself political. It involves choices — some things will be recalled and others forgotten, and from that process emerges a certain understanding of the past. But critics of war commemoration are themselves engaging in politics. To criticize one kind of remembering is, by definition, to make a political statement. It is to fall into the same trap as that which is being critiqued.

Such philosophical debates have never obscured the real focus of remembrance: the people who died.

As long as Canadians have been commemorating war, it has been about people. Even with fulsome phrases and allegorical figures adorning so many war memorials, they have always been about people. The monument to Wolfe and Montcalm makes no mention of the battle in which they both died.

The great arch in Halifax is named after two soldiers, not the war that claimed their lives. And when the National War Memorial in Ottawa was dedicated in 1939, there were no ringing phrases inscribed in the stone, just a single line: 1914–1918. The allegorical figures atop the arch were too high to make much of an impression on passersby; instead, the eye was drawn to the figures under the arch, powerfully realistic renderings of the men and women who actually fought the war.

Nor was commemoration in Canada characterized by the tendency to name only the officers and reduce everyone else to a number. None of the nine young men commemorated on Toronto’s Fenian Raid monument were officers.

The star of the striking Boer War memorial in Cayuga, Ontario, is William Knisley, a lowly corporal.

The citizen army that carried Canada’s colours in the world wars accentuated this practice, which might be called democratized commemoration. They were civilian soldiers, men and women who went forth from their communities to fight and who would return to their civilian lives when the fighting was done. It was essential that they be named, for only then could they be remembered.

This assumption underpins many of the manifestations of the way Canada remembers war. It is behind the obsessive record-keeping of the 1920s, as communities compiled exhaustive lists of townspeople who had served. It is behind the consensus that those names should be inscribed on memorials, or at the very least become part of the public record. And it is behind the widely held assumption that those names should be listed, not by rank or class, but according to the democracy of the alphabet (although nursing sisters occasionally jumped the queue and headed the list).

It is also the central principle behind the work of the Imperial War Graves Commission, of which Canada was a founding member in 1917: All war dead would be commemorated with identical headstones, regardless of rank or honours. (The only exception is John McCrae, who is buried beneath a standard headstone but has a commemorative bench in his honour in Wimereux Communal Cemetery in France.)

The same thinking was behind the creation of the seven Books of Remembrance, the first of which was completed in 1942 — when it was already clear that there would have to be a second book. The names of the dead are listed by year in alphabetical order, with no special consideration shown to the high and mighty.

In the book, for 1916, Major-General Malcolm Mercer, commanding officer of the 3rd Division, barrister, pre-war militia officer, and a leading light of Toronto society, is followed by Thomas Mercer, a simple seafarer from Beaver Cove, Newfoundland, who enlisted in the infantry in Halifax in 1915.

No matter what commemorative activities are planned by the federal government, it seems likely that community and private initiatives will follow these old patterns — focusing on the people rather than the principles, and affirming the democracy of death in wartime as it was understood in the last century.

Those traditional practices will draw new force from some characteristics of the twenty-first century, such as the tendency to see the past nostalgically. We live in a complicated world, and so we look back at a time when things seemed so much more simple: We knew who the enemy was, and we knew what had to be done to defeat them.

Today, when the enemy could be international terrorism or multinational corporations, religious fundamentalism or climate change, we yearn for a black-and-white world like the world of the 1910s or the 1940s.

Curiosity will be an even more powerful factor in how these commemorative projects are conceived and embraced. In the twenty-first century, the past is regularly recreated and there are many opportunities for people to “time travel” — living history museums, re-enactor groups, first-person video games.

With the world wars about to occupy a commanding position in the commemorative landscape, the lure of placing oneself in history will be even more powerful. How would I have reacted in the same situation? It is an unanswerable question, even for people who assume their beliefs are rock-solid.

During the First World War, French Mennonites had to decide between their faith’s historic commitment to non-violence and resisting an invader that had already committed countless atrocities against Belgian and French civilians; most of them chose resistance.

Thousands of campus pacifists in North America in the late 1930s signed declarations that they would never go to war, even if their country was invaded. A few years later, the vast majority of them had enlisted voluntarily. Because the questions are unanswerable, they are that much more appealing to the imagination.

When I was fifteen years old, would I have lied about my age to get into the infantry, as so many boys did in 1916? What about the sheer physical endurance that makes our “roughing it” wilderness trek seem like a weekend in a luxury penthouse? Could I have borne it? Would I have had the mental strength to endure life at the front? We should be amazed not that so many young men suffered from shell shock but that not all of them did.

More broadly, we are engaged by a curiosity about ordinary people who, seventy-five or a hundred years ago, found themselves in extraordinary circumstances. We wonder about the young man in uniform who smiles down from the old photograph in the high school. About the family whose grief is manifest in the glorious stained-glass window in the church.

About the young woman who trained to be a nurse in the hospital and whom war robbed of a career of compassion and caring. The coming years of commemoration can have meaning if we as a society decide that such people don’t deserve to be forgotten. Behind each name is a life, behind each photo a person worth knowing. Remembering is our obligation, but also our privilege.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!