The Trial of Aaro Vaara

In 1928, Sudbury, the centre of nickel mining and smelting in Ontario, bore more than a passing resemblance to Dante’s Inferno.

There, the Canadian Shield, denuded of its pine forest, exposed itself in strange outcroppings of black rock while near the mineheads slag heaps created more black hills, and the old, abandoned process of roasting ore in the open air had left vast pits like scars on the Earth’s face.

Although the roasting beds no longer smouldered for months at a time, the yellow sulphur fumes, channelled through giant stacks, continued to cast a permanent pall over the town.

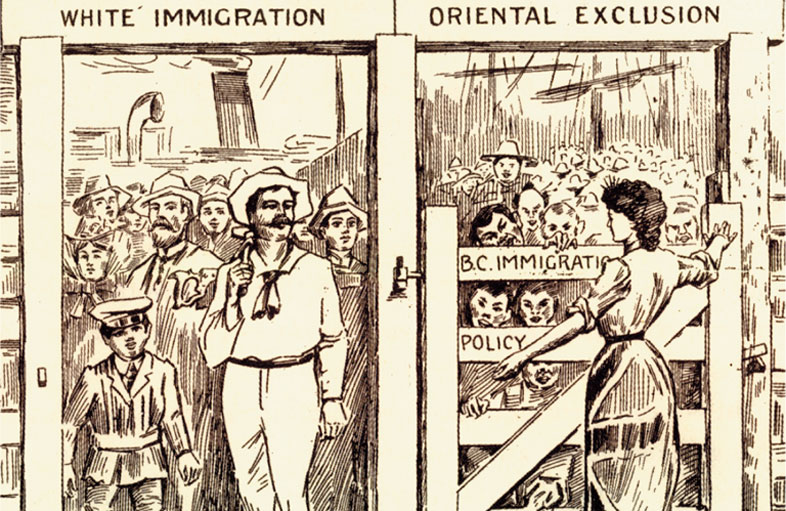

The mines and smelters of the International Nickel Company and the British-owned Mond Company were worked by French-Canadian and immigrant labour. Of the latter, the majority were Finns. Unassimilated, they retained their own language and most spoke little or no English.

It was widely believed that they were communists and it was a fact that the large Finnish Organization of Canada had joined the Communist Party of Canada as a bloc. (Together with ULFTA, the Ukrainian Labour-Farmer Temple Association, the FOC provided the numerical strength in an otherwise insignificant Communist party.)

Cloistered in their own communities, many Finns looked to the FOC organ, Vapaus, as a guide to living in this new land. Vapaus wielded considerable influence, not only in Sudbury where it was published, but among the Finnish families living in isolated homesteads along the railroad lines throughout northern Ontario. As with all the communist press, its language and content tended to be inflammatory.

“Will the King die is all the same to us. The social order will be equally oppressive to the poor, whoever is king. Capital really rules in modem society.”

It was not often that Vapaus, like the bourgeois press it despised, concerned itself with the Royal Family. In early December 1928, however, it ran two pieces on the monarchy.

George V was seriously ill with pleurisy, and Canadian newspapers, Liberal and Conservative, were devoting front page coverage to the daily bulletins that came over the wire on the King’s health. During this same period, there were reports of great distress in the coalfields of South Wales. It was said that some of the out-of-work miners could not feed their families and that children were facing starvation.

In the December 4 issue of Vapaus, an article appeared on the royal illness. In translation it read:

“George is said to be suffering from whooping cough. He is supposed to have gotten it when he had to stand bare-headed outdoors for two minutes at a certain festivity. Now one telegram after another is sent out informing the devout worshippers of the kingship of the slightest move which “our King” makes resting on his pillows.

Will the King die is all the same to us. The social order will be equally oppressive to the poor, whoever is king. Capital really rules in modem society.

Kingship being only a lawful piece of decoration while gluttonous financiers riot with the wealth secured through workers’ blood and sweat Of the King’s condition the whole world is informed through telegrams. But is anything wired of the condition of the millions who right now live in utter misery in the very heart of the British Empire? No, they are not telegraphed about Efforts are made to conceal such matters, they not being in accord with the fomenting of patriotic enthusiasm.

So, will the King die? If he does we hope royalty will die with him and a workers’ republic take its place. A change of kings will not better our conditions, no matter who holds the scepter. Only the rise to power of the workers themselves will save us from the curse of capitalism.

The same issue contained a flippant article on the Prince of Wales whose African safari was interrupted by his father’s illness.

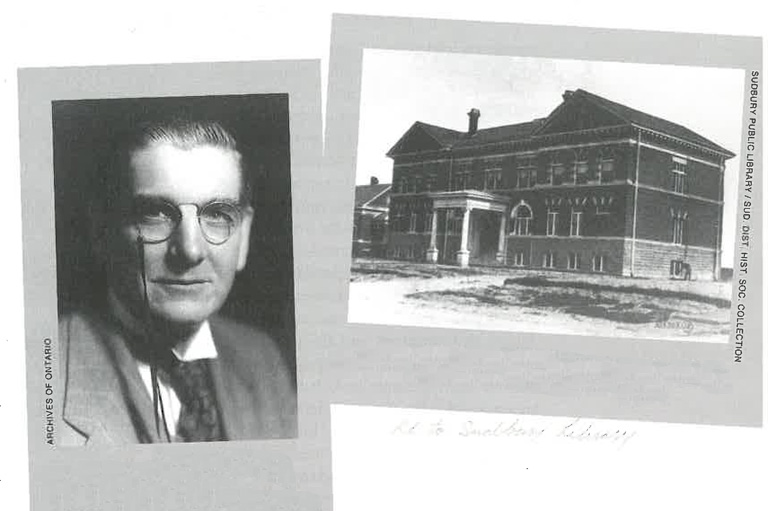

On the evening of December 13, the editor of Vapaus, Aaro Vaara, was arrested at his rooming house by the Sudbury chief of police and charged with seditious libel under Section 133 of the Criminal Code. In announcing the arrest in Toronto, the Ontario attorney general, Colonel William Price, said that his department paid little attention as a rule to the communists who were just publicity-seekers, but in this instance the matter could not be ignored.

“It is a serious thing to attack the King,” Colonel Price told the press, “and there are several sections of the Criminal Code dealing specifically with that kind of sedition.” He concluded, “No one is allowed to even belittle the reigning sovereign.”

How had an article from a Finnish-language paper come to the attorney general’s eye? The instigator was one Reverend T.D. Jones, director of a United Church Home Mission in the Sudbury region.

“Prompted by loyal motives,” according to the Toronto Globe, he brought the Vapaus articles to the attention of the press and the authorities. Bearing in hand a translation prepared by a Finnish minister associated with him in his missionary work,

Jones marched into the offices of the Sudbury Star. The paper ran the articles in full, under the headline “Vapaus Launches Tirade Against Royalty. Obviously Treasonable Article Translated.”

The matter was immediately taken in hand by Sudbury’s Crown attorney, R.R. McKessock, who, according to his law partner, was “highly incensed.” Indeed, King George may well have had no more loyal subject in the Dominion than Major McKessock.

Then in his fifties, he was a handsome man, almost the stereotype of a British officer, with a neatly trimmed moustache and military bearing. In 1914, he had bid goodbye to his wife and child and closed up his law practice to enlist for overseas duty. He had served in France until taken prisoner at the battle of St. Julien. Awarded the Military Cross for bravery, he returned to Sudbury to a hero’s welcome.

After the war, McKessock resumed his law practice and his position as part-time Crown attorney, but much of his time was devoted to the formation of the Great War Veterans Association, the forerunner of the Royal Canadian Legion. The Vapaus articles were anathema to him.

“Any remarks seeking to belittle, disparage, or ridicule royalty may be interpreted as treason,” he informed the Sudbury Star. “I intend to investigate.”

Although the Toronto Globe, with its metropolitan bias, insisted that McKessock acted on instructions from the attorney general, the initiative may have originated in Sudbury. Colonel Price was quoted as saying, “I am glad to know that the local Crown attorney has already taken action and is conducting an investigation.”

As it happened, McKessock had access to the attorney general beyond that of most Crown attorneys. Price was his cousin and had studied law with him.

McKessock’s patriotic indignation was heartily shared by the Legion. The Sudbury branch was extremely anti-communist. For some time it had been calling for an inquiry into the Pioneer School at Liberty Hall, the Finnish community centre, which it asserted was nothing more than a breeding ground for Reds. The Vapaus articles slurring the king had the Legion up in arms. In instituting legal proceedings, McKessock had the Legion marching squarely behind him.

While the Legion was more vociferous, it accurately expressed public opinion. The Sudbury Star articles had “an electrifying effect” upon the townsfolk. Given the popularity of the monarchy, heightened by human-interest stories of the sick king, English-speaking Sudbury was shocked.

And strong anticommunism, instilled by the priests, put the French-Canadian population on the same side. Public feeling ran so high that a petition signed by “the very best elements” was later presented to the House of Commons asking for Vapaus’ suppression.

Thus Vaara’s arrest was the main topic of conversation not only in the Legion hall but up and down Elm Street and in all Sudbury’s many hotels and beer parlours. In police court the following morning, Vaara was released for a week on bail of $10,000 (an enormous sum at the time), which was supplied by the FOC.

In a special midnight edition, Vapaus called the charge of sedition absurd. It cited similar articles published with impunity in the radical press in Great Britain and even in The Worker, the Communist Party of Canada’s organ.

The question arises whether there was more to the Vaara prosecution than patriotic outrage. In the first place, it appears that the Reverend T.D. Jones was prompted by more than “loyal motives.”

He admitted in the Globe his missionary work was severely hampered by the Red Finns and that he and his fellow United Church missionaries endured considerable ridicule in the pages of Vapaus. It would seem that Jones was fighting for souls with the Communists and losing. Personal spite undoubtedly played a part in the Vaara affair.

There was also the fact that Vapaus was running a campaign to organize the Finnish miners. There were no unions at International Nickel, nor at the nickel mines owned by the Mond interests of Great Britain, nor, for that matter, at any of the northern Ontario mines.

Earlier unionization attempts had proved too weak to survive the mine operators’ opposition. Company police posted at the railway station hustled all known union organizers back on the train. Workers who agitated for unions were promptly fired.

The official Communist Party line on the Vaara case was that it was a deliberate attempt to get rid of all those who were helping to organize the nickel industry. The Worker predicted that “with a move on foot to organize the unorganized in basic industries, and nickel mining is one of the most important, the government authority will come down with an iron fist.”

There may have been something to these suspicions. A merger between Inco and Mond Nickel was in the wind. That autumn Sir Alfred Mond, newly created Lord Melchett, had visited Canada, fuelling speculation on Bay Street and St. James Street. Inco’s stock was soaring, with speculators driving it up twenty-two points on a single day in anticipation of the merger.

In what was regarded as a preliminary to merger, Inco’s parent company in the United States transferred ownership to its Canadian subsidiary to elude the much tougher American antitrust laws. Out of the merger the Sudbury company would arise as a giant corporation controlling ninety per cent of the world’s supply of nickel.

Labour unrest during this critical period would have been inopportune, to say the least. Did the provincial government, as The Worker claimed, intervene to silence its editor because Vapaus was spearheading a drive for unionization among the hitherto docile Finnish miners?

The Tory administration at Queen’s Park was the recognized benefactor of the mine operators. The government’s policy was based on the premise that Ontario’s prosperity was inextricably bound up with a profitable mining industry. Premier Howard Ferguson justified a minimal mining tax on the grounds that the industry was highly speculative and had to attract risk capital.

As a result, little of the enormous mineral wealth pulled from the earth of northern Ontario during the mining boom of the 1920s profited the public treasury. Nor did it ease the hard life of the miners who toiled to bring it forth. Still it is undeniable that northern Ontario’s greatest prosperity occurred during these robber-baron days. The timing of the Vaara prosecution lends credence to the Communist accusations, suggesting that it may have been another instance of Queen’s Park’s protective attitude towards the mining corporations.

In any event, Premier Ferguson abandoned his benign neglect of the Communists over the Vaara affair. “Communism,” he declared in the Globe, “will be rooted out.”

On December 28, a preliminary hearing was held in Sudbury. It was largely a family affair, with Crown attorney R.R. McKessock appearing for the prosecution, and his brother, Magistrate J.S. McKessock, sitting on the bench. In a northern mining community this relationship occasioned no adverse comment. Indeed the townsfolk were proud to have men of the calibre of the McKessocks among them.

Besides, the administration of justice was an informal process in northern Ontario, with none of the morning-suit dignity of magistrate court in Toronto. J.S. — a balding, skinny man far less prepossessing in appearance than R.R. — whiled away the hours between sessions playing cards with the boys upstairs until someone called “court’s starting,” and down he came.

Counsel for the defence in the Vaara trial was Arthur Roebuck from Toronto. Of patrician appearance, with a pince-nez on a black ribbon and an old-fashioned high collar, he was an unlikely looking advocate for an immigrant communist in a mining town. But Roebuck had ties with the north.

Formerly owner and editor of a couple of small-town newspapers in northeastern Ontario, he had tried unsuccessfully (as a Liberal and a Labour candidate) to represent the area both in the House of Commons and the provincial legislature. He had come to the practice of law late in life, almost certainly with a political career in view.

After his electoral defeats he opened a law practice in Toronto, but many of his clients, such as the FOC, were in the north. Roebuck had all the membership cards of the Establishment, yet unlike most of its members he had a deep sympathy for the underdog. Tim Buck, the Communist Party of Canada leader, aptly described him as “a very liberal Liberal.”

At the preliminary hearing, the McKessocks found themselves confronted by the most hostile of witnesses and the most recalcitrant of translators. The Crown attorney had subpoenaed the Vapaus business manager with orders to produce the paper’s subscription list. This the witness refused to do, fearing no doubt that Vapaus subscribers would find themselves visited by the RCMP or by immigration officers.

Similarly, the translator called by the Crown refused to translate the articles, stating that his sympathies were all with the defence. Only when threatened with contempt of court did the two men comply — and not before the business manager had erased 500 of the 4,000 names on the list!

These problems resolved, the lawyers began their gentlemanly sparring. Roebuck contended there was no evidence that Vaara was responsible for the articles in question, and, moreover, while these may have been impolite they were not seditious.

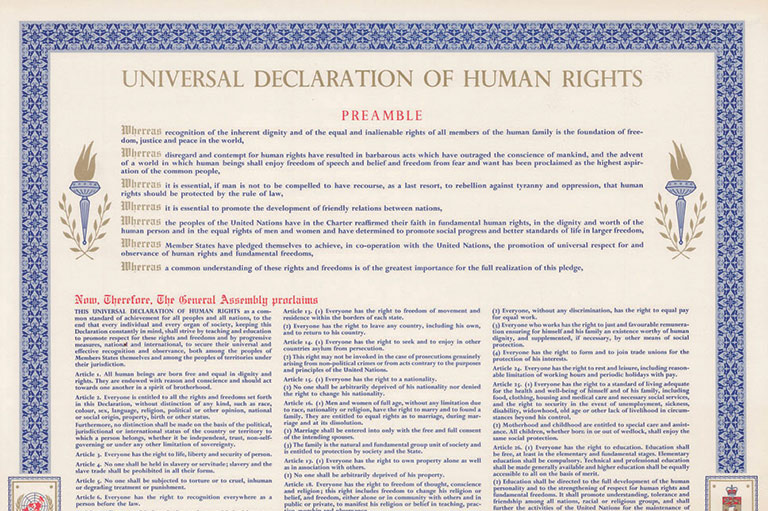

Sedition, he asserted, was the intention to incite change in the form of government by the use of force; it was not illegal, he went on, to advocate change in a lawful manner, as the Vapaus articles did. On these grounds he asked the court to dismiss the charges.

The Crown attorney replied that even if the editor did not write the articles, he had the last word, and the responsibility for publishing them. As for sedition, he stated it was that which disturbed the tranquillity of the state or brought into hatred or contempt the person of the king. Both fitted the present case.

“The whole tone of the Vapaus articles has stirred every red-blooded British subject,” McKessock declared, and in his view people would not remain tranquil in the face of such utterances.

Having heard the arguments, Magistrate McKessock found the accused responsible for publication of the articles. As for the second ground for dismissal advanced by the accused’s lawyer, “he could not see but that the words were an incitement and did disturb the tranquillity of the State.”

The magistrate was particularly rankled by the paragraph about King George catching whooping cough by standing outside for two minutes at some festivity. “If that isn’t trying to bring royalty into contempt I don’t know what is,” he concluded with feeling. As expected, Vaara was committed for trial.

On February 19, 1929, Aaro Vaara was tried before an Ontario Supreme Court judge and jury. To one Communist present in the Sudbury court-house, the power of the Establishment was personified by the “sleek, satisfied judge.”

Mr. Justice William Henry Wright was a huge, florid man known as “Butcher” Wright to the irreverent young lawyers who appeared before him. His nickname was said to allude to his beefy and rather common appearance and not to his dispensation of justice.

Still, Wright was a daunting presence on the bench, insistent on the strictest rules of court procedure and a rigid adherence to his rulings. No judge was freer with citations for contempt. Court decorum, however, he saw as a one-sided obligation: he himself was given to outbursts of temper.

The courtroom was crowded with immigrant workers, friends, and supporters of the accused. As if to impress upon them the dread power of British law, His Lordship warned that silence must be observed or he would put the offenders in jail for contempt of court.

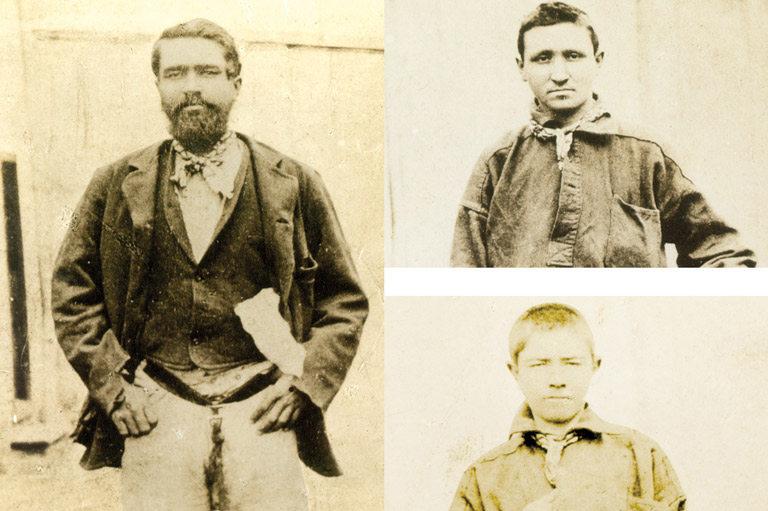

One spectator seen whispering to his companion was summarily ejected from the room. Amid the suppressed excitement, the prisoner in the dock, a clean-cut man with a level gaze and light, wiry hair springing back from a high forehead, remained impassive as if, in his mind, the verdict of guilty was already in.

Prominent among the host of witnesses was the Reverend T.D. Jones; of him Attorney General Price would later say that he had been “helpful to us at the time of the Vapaus prosecution.”

The indictment cited both Vapaus articles in full, and early in the proceedings Roebuck objected vigorously on the ground that the offence was not specific enough. What exactly did the Crown object to? He inquired. Surely the references to the Prince of Wales could not be called seditious since the heir apparent was a private citizen.

On this minor point the defence counsel enjoyed his only approbation from the bench in the day-long trial. While overruling Roebuck’s motion to quash the indictment, His Lordship agreed that “it does not constitute a crime to speak in a slighting manner of the Prince of Wales,” adding “however reprehensible it may be.”

Having tried and failed to have the case dismissed, Roebuck entered a plea of not guilty.

A row of Finnish witnesses subpoenaed by the Crown sat, awkward and uncomfortable, in their best suits. But McKessock had changed his mind and only two were called to testify. At the end of the case for the prosecution, Roebuck announced that he would not call any witnesses and launched into his address to the jury.

Looking every inch a gentleman of the old school, he began by associating himself with the monarchical sentiments of the twelve men in the jury box. However, he adjured them, “we should use a little of the patience and tolerance which our King exercises” in considering the position of the immigrants.

“How different are the advantages you and I have had and those of others who have recently reached our shores.” (Clearly, Vaara was not being judged by his peers, immigrants like himself, but by middle-class, native-born citizens.) Roebuck suggested that Vaara may have developed a distaste for monarchies from the undemocratic rulers of Germany and Russia.

He asserted that the Crown had not proved by a tittle of evidence that Vaara was the author of the articles. Nevertheless, he took the precaution of conducting the jury through a line-by-line analysis of the offending portions, arguing there was no manifest intention to incite to violence. Moreover, what was said was no less than the truth.

“If two million are suffering from famine in England isn’t it wise and well that we should say so?”

Coming to the most objectionable part, “Will the King die is all the same to us,” Roebuck contended that this was not an attack on the king; it was simply a declaration that society was really ruled by large-scale capital. Having completed his exegesis, he summed up for the jury: “Analyzed, what’s it all about?”

The hostile Globe wrote that defence counsel “left no stone unturned in pressing for an acquital.” To The Worker’s reporter, it was “an eloquent appeal.”

Although McKessock did not indulge in the high-flown oratory then common in the courtroom, according to his law partner he would belabour a point if he thought the jury was missing it. In his address he enlarged upon the offensive tone of the articles, not excluding the ruled-out references to the enormously popular Prince of Wales.

The Crown took occasion, he said, to give lie to the insinuation that the heir to the throne was callous. He reminded the jury that the prince had made personal appeals to alleviate the conditions of the Welsh miners. Therefore was there any reason to broadcast the opposite impression?

The Crown attorney asserted that the articles were intended to set class against class, Finns against English. To prove sedition it was merely necessary to show that the writings would set one class of His Majesty’s subjects against another. The Crown had shown this. McKessock rested his case.

In his charge to the jury, the judge dismissed Roebuck’s claim that the articles could not be attributed definitively to Vaara. He was the chief editor as testified to by witnesses and therefore responsible.

“Is there any evidence here that any person other than the prisoner wrote or published these articles?” he asked. He instructed the jury that the accused was guilty on this count beyond a reasonable doubt — the proof required in a criminal charge.

“You are to say whether this article was intended to bring into hatred or contempt the person of His Majesty or of the government,” His Lordship directed the twelve men in the jury box.

“If you come to the conclusion that it is calculated or intended to excite ill-will between the different classes of the King’s subjects, that is, between the workers referred to in the article and the capitalist class, or the other classes of the country, then that might be deemed to be seditious.”

After the jury retired, Roebuck took strong exception to the judge’s instructions that the accused was responsible for the articles. Surely this was a point for the jury to decide. Wright waved away the objection; it had been amply proved in evidence, he stated impatiently.

The jury was out three hours, raising hopes in the defence of a split decision, but when the dozen men filed in they declared a guilty verdict. Roebuck requested that each juror state his verdict individually.

The judge was clearly pleased with the jury. “I think your verdict is well supported by the evidence,” he commended them. Then turning to the prisoner he inflicted a verbal flogging:

“There is a line to be drawn between honest criticism and a stirring up of strife against His Majesty the King. Your crime is of an unusual character. You came to this country to become a citizen and not to criticize its customs. Your act was a peculiarly heartless thing and you do not deserve the slightest consideration. There may have been honest criticism; that is not so serious as your inhumane attack.”

Vaara was sentenced to six months in prison and a fine of $1,000. If the fine was not paid he would have to serve an additional two years.

“With apparent calm,” observed the Toronto Daily Star reporter, “Vaara buckled on his overshoes, took his hat and coat and left the room under escort.”

It had been a hard day for Roebuck as well. The judge had supported the Crown throughout. Every motion Roebuck advanced had been denied.

“It was a day of protestation without avail for the defence counsel,” the Globe remarked cheerfully. Afterwards, Roebuck announced that on instructions from his client, the Finnish Organization of Canada, he would launch an appeal.

On March 6, 1929, Vaara’s appeal was heard in Osgoode Hall in Toronto. Essentially it was grounded on the trial judge’s prejudiced charge to the jury.

Roebuck argued that the judge failed to state material facts favourable to the defence or stated inaccurately and prejudicially portions of unfavourable evidence. Furthermore, he claimed that the judge did not properly instruct the jury that the burden of proof was on the Crown, particularly with regard to the charge that the accused was responsible for the articles.

In dismissing the appeal orally, Chief Justice Francis Robert Latchford dwelt upon the untimeliness of the remarks on the king’s health.

It was no difficult matter to prove sedition in 1929. While Mr. Justice Wright was patently prejudiced against the accused, he was on firm legal ground in his instructions to the jury as to what constituted sedition. The Criminal Code did not define the offence. It was enough under the common law at that time to utter strong words against the government.

In fact, for Mr. Justice Wright, the Vaara trial proved to be a rehearsal. In 1931 he would preside at one of Canada’s most famous state trials — the trial of Tim Buck and eight other Communists accused of sedition under the notorious Section 98 of the Criminal Code, enacted in the wake of the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike to indict its leaders.

But in 1928 Arthur Roebuck was ahead of the law by more than twenty years when he argued his client’s innocence on the ground that there was no incitement to violence. It was not until the 1951 Supreme Court decision in the Boucher case that inciting to violence or public disorder became a necessary element in proving sedition.

After serving his sentence, Aaro Vaara went back to editing Vapaus. The onset of the Depression and the Bennett years sharpened his criticism of capitalism and the king, whom he regarded as its figurehead. In 1932 he was arrested in a police raid on his newspaper, transported to Halifax, and deported without trial to Finland.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!