The Mystery of Mr. McIntosh's Apple

-

Apple tasting at Spadina Museum.Derek Matthew / Flickr.com

Apple tasting at Spadina Museum.Derek Matthew / Flickr.com -

Neglected site of the original McIntosh tree Dundela, Ontario.Sophie Kneisel

Neglected site of the original McIntosh tree Dundela, Ontario.Sophie Kneisel -

Tree grown from a graft of the original McIntosh tree, Smyth's Apple Orchards, Dundela.Sophie Kneisel

Tree grown from a graft of the original McIntosh tree, Smyth's Apple Orchards, Dundela.Sophie Kneisel -

Allan McIntosh with the original McIntosh Red tree around the time it was damaged by fire in the 1890s.

Allan McIntosh with the original McIntosh Red tree around the time it was damaged by fire in the 1890s. -

The 1996 Canadian Silver Dollar coin, designed by artist Roger Hill, to commemorate "Canada's Premiere Apple".Royal Canadian Mint

The 1996 Canadian Silver Dollar coin, designed by artist Roger Hill, to commemorate "Canada's Premiere Apple".Royal Canadian Mint -

Apple harvest at Abboysford, Quebec, 1930s.Library and Archives Canada

Apple harvest at Abboysford, Quebec, 1930s.Library and Archives Canada -

The McIntosh accounts for over half of the 17 million bushels of apples produced in Canada every year.Foodland Ontario

The McIntosh accounts for over half of the 17 million bushels of apples produced in Canada every year.Foodland Ontario -

Ontario McIntosh apple logo.Ontario Apple Marketing Commission

Ontario McIntosh apple logo.Ontario Apple Marketing Commission

McIntosh had come to this cold and unforgiving country in 1796 from the friendly, civilized region of the Mohawk Valley, fleeing family disdain for the unforgivable sin of falling in love with an unacceptable mate.

He had settled on land near the town of Iroquois on the St. Lawrence River, but now the woman who had caused such upheaval in his life was gone and he was several miles further north, married to Hannah Doran and trying to tame the land he had traded with her brother.

Only one-quarter of an acre of this so-called farm had ever been cleared and even that section of the wilderness had grown up again, the young trees towering above his head.

But in amongst them, he kept coming upon little seedlings, strong and youthful, and decidedly unlike the others. Apples, thought John McIntosh, apples growing in the Canadian bush? He spared them.

About a dozen seedlings were soon transplanted to his garden nearby. By the following year all but one had died. He nursed it and it slowly grew. When it bore fruit, red-blushed and round, he tasted it, tart on the tongue.

Today the McIntosh is produced in greater quantities than any other apple in Canada and the north-eastern United States, and is grown in orchards around the world. Every tree, and therefore every McIntosh apple that has ever been eaten or put into a pie or into juice or cider, is a direct descendant of that little seedling that mysteriously appeared in the Canadian woods and tenaciously clung to life. It was, when John McIntosh found it, the first and the only one of its kind in the world. To this day no one is certain how it got there.

The way in which apples reproduce when unchecked by human interference creates much of the mystery. Apple trees are not “self-fruitful”; in other words, the seeds within their apples will not reproduce the same variety as the parent tree.

Only by grafting a variety onto the trunk of another tree can that variety be maintained. The orphan that McIntosh found in the bush that day, likely grown from seeds of an apple core tossed on the ground by a passerby, was naturally cross-pollinated, an offspring of unknown ancestors.

The apple most often theorized as a parent is the Fameuse, known in English Canada as the Snow. This is based on several common characteristics and the Fameuse’s popularity in Quebec before 1811. There were no apples (other than crab) in North America prior to the appearance of Europeans; by the seventeenth century they had made their way westward with settlers and it would make sense that travelling Quebecers, moving through the woods around Matilda Township, 95 kilometres west of their border, would be carrying Fameuse apples.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

But in 1970 W.H. Upshall of the Horticultural Experiment Station at Vineland, Ontario, maintained that trials with the Fameuse as progenitor had not been successful, and suggested Fall St. Lawrence and the Alexander as potential forebears.

This is contrary to conclusions drawn by other experts, like Roger Yepsen, who unequivocally stated in his 1994 book Apples, that the McIntosh is “a talented cross between Fameuse and Detroit Red.” More than 80 years earlier The Canadian Apple Growers’ Guide had hedged its bets, simply calling the Mac, “of Fameuse type.”

So the mystery of the McIntosh, probed only by educated guesses, remains.

John McIntosh likely cared little about where his wonderful new apple tree came from — all he knew was that he had to reproduce it. But his experiments with seeds kept giving him other varieties. His one tree remained, ready to disappear from history should it be destroyed.

A century and a half later Olive McIntosh, widow of John’s great-grandson, sits in her home in Morrisburg, Ontario, not far from the Dundela homestead where she once lived. She opens an old wooden box filled with family heirlooms, the greatest of which should be a national treasure: a chunk of the original McIntosh tree.

Setting it on the kitchen table, she explains how John solved the reproduction problem: “Luckily, a travelling hired man just happened to come along one day (about 1835) and he showed John and his son Allan how to graft.” Thus the McIntosh survived.

Olive, whose children and grandchildren carry the McIntosh name in the area, likes to tell stories about Allan. It isn’t hard to see why. He was not only an extraordinary character, but deserves much credit for making the Mac what it is today.

By the late 1830s he was in charge of the family nursery and orchard, succeeding his mother Hannah, the real apple expert of the previous generation (at first, Macs were called “Grannys” in her honour). He began grafting in a serious way, producing bushels upon bushels of what were becoming known as McIntosh Reds. This bearded, ingenious man also experimented with fungicides (the Mac was susceptible to scabs), hewn cedar troughs to drain the orchard, and cross-pollination.

He sold, and apparently gave away, trees throughout eastern Ontario and the north-eastern United States, where he sold apples to McIntosh relatives in Vermont. He was known in the Matilda area as a medicine man and travelling preacher. Olive’s family treasures include fire-and-brimstone sermons written in his hand. Glancing through their pages, one imagines Allan booming some of its contents at slightly shaken audiences, admonishing them to be on guard for “Satan and his hellish crew”.

Despite Allan and his brother Sandy’s efforts, it was many years before the McIntosh Red became prominent. Indeed it wasn’t until 1870, nearly a quarter of a century after John’s death, that it was officially “introduced” and named; it made its first appearance in print six years later (in Fruits and Fruit Trees of America); and began to sell in truly large numbers after 1900.

The Mac’s hardiness, appearance and taste made it a contender from birth, but it was only when turn-of-the-century advances in the quality and availability of sprays took care of its scabbing problem that it realized its incredible commercial potential.

By that time things had changed at Dundela. An 1894 fire that burned down the family home badly damaged the original tree. Though Allan made extensive efforts to nurse it back to health, it produced its last crop in 1908 and fell over two years later, almost exactly a century after it had been discovered in the woods. Allan died in 1899, Sandy in 1906, so it was grandson Harvey (1863–1940) who was at the helm when the family apple became world-famous.

As we approach the end of the twentieth century, it accounts for more than half of the 17 million bushels of apples produced in Canada every year, and is our most commonly grown fruit: 130,000 metric tonnes come from Ontario alone, though it also thrives in Quebec, Nova Scotia and British Columbia (where it was introduced in 1910).

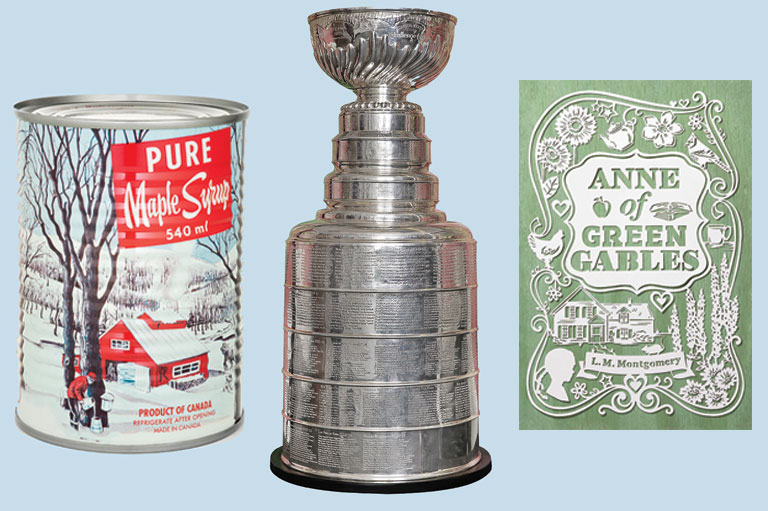

In the U.S. it ranks behind only the two Delicious varieties and has a personal computer named for it; overseas it is one of few successful North American varieties.

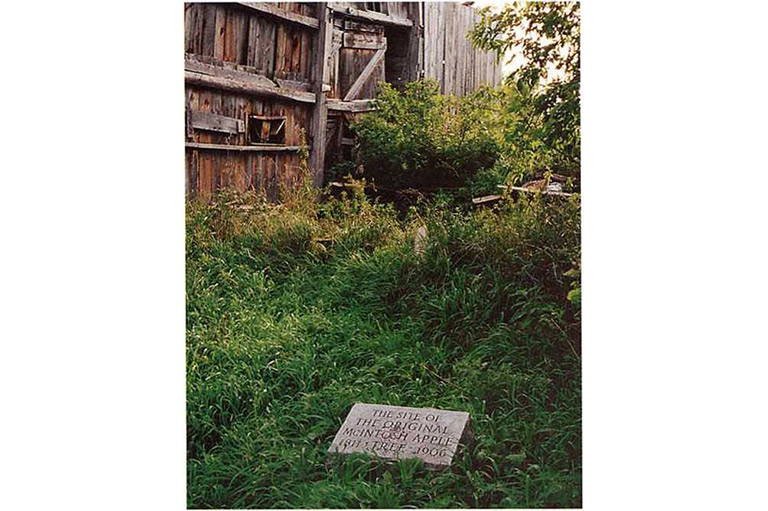

It is hard to imagine anything that we grow for consumption that is more Canadian than the Mac. But today at the site of the first McIntosh apple tree in the little village of Dundela there is only token recognition. Drive south-east about 45 minutes from Ottawa or north 10 minutes off the 401 and turn onto county road 18 and you will see for yourself. But don’t blink, or you’ll miss it.

There is no orchard on the McIntosh homestead anymore, only a couple of houses and broken-down barns. A plaque, erected by the Ontario Archaeological and Historic Sites Board, stands a few steps from the road, next to a monument put up in 1912 bearing the erroneous information that John McIntosh found his seedling in 1796. The latter also tells any who happen by that the original tree was some “20 rods” (100 metres) to the north.

Walk around to the rear of the property in search of that historic site and you will see how we treat our national treasures. Though local residents will tell you to have a look, you probably shouldn’t, because once you are wading through the knee-high grass, you are on private property.

The owner, who insists in letters to various newspaper editors that he is angry about sightseers and would be happy to show them around if they would only ask, lives 80 kilometres away in Ottawa. If you do venture through the hole ripped wide in the rusty fence, you will find yourself looking for a needle in a haystack, or at least a golf ball in decidedly long rough.

Finally, there it is, a little stone marker nearly buried beneath weeds behind a collapsing barn. “The site of the original McIntosh apple tree. 1811–1906”.

A minute down the county road to the east Sandra Beckstead sells Macs by the ton at Smyth’s Apple Orchards, a thriving 100-acre tract begun in the mid-1800s by her ancestor Sam Smyth, neighbour and colleague of Allan McIntosh.

A tree grown from a graft of the original McIntosh sits in their front yard. She is bright and friendly, a breezy proponent of apples and apple eating. Only when the state of the McIntosh homestead is discussed does her mood dip.

“They have signs on the 401 for the marina and the golf course and that sort of thing, but nothing for something that is part of our history, something that we all should know about and be proud of,” she says.

She works hard at redressing this wrong. In one corner of her store, where information fills the walls, and life-size dolls of John and Allan McIntosh look on, you can take a veritable history class; and every year school children are invited to the orchard. Customers are told not only about the Mac and its heritage but of the many world-renowned apples it has parented: the Cortland, the Lobo, the Joyce, the Melba, the Macoun and the Early Mac, to name a few.

In the summer of 1996 a few louder voices joined Sandra’s. The Ottawa Citizen published an editorial decrying the political circumlocution and apathy that has left this potential symbol invisible amongst weeds (provincial funding has fizzled, the township has no money to buy the land and the county’s roadsign campaign has been derailed, or at least delayed, because of bureaucratic changes).

That same month the Toronto Star printed a front-page story entitled “Rotting to the Core” with a photo of Olive’s son Harvey on the unkempt site. The Mac also appears on the 1996 Canadian silver dollar, though oddly it commemorates the 200th anniversary of John McIntosh’s arrival in Canada rather than celebrating the year he found the tree.

The story of the single seedling in the northern bush that parented millions of one of the world’s most popular apples, is an intriguing and romantic one. But Canadians, ostensibly anxious to have national symbols, have somehow left it by the roadside.

How the Macintosh computer got its name

When Steven Jobs and Stephen Wozniak started their computer company in 1976 (in the garage of the home of Jobs’ parents in Cupertino, California) they wanted a fresh, non-traditional name for their new personal computer. Jobs in particular was an advocate of natural foods, so when someone suggested “Apple” — a food the health-conscious Jobs was fond of — at a brainstorming session just prior to the deadline for filing a company name, it was an image that appealed to Jobs and the others.

Within four years the personal computer industry boomed. By the end of 1982 there were more than 100 companies manufacturing personal computers. In 1983 Apple entered the Fortune 500.

According to Frank Rose in his book West of Eden, Jef Raskin, a former college professor and longtime computer hobbyist who worked for Apple, got permission in 1981 to “build his own dream computer. He wanted it to be inexpensive, portable, and as easy to use as an appliance. He called it Macintosh, [sic] after his favorite kind of apple.”

The Macintosh was introduced in January 1984; by 2015 the company sold over 317 million “Macs.” Apple Canada was established in 1980 as Apple’s first subsidiary outside the United States. In June 1995 they shipped their one-millionth computer, to a school in Nova Scotia.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement