The Frozen Man

In March 1959, my mother came across an article, entitled “The Living Snowman of Grindstone Island,” in Coronet magazine. The article told of a violent snowstorm in the Magdalen Islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in 1871. For days, local folk were terrified by tales of a seven-foot-tall monster wandering around and growling at anyone who ventured outside.

Finally, one evening, the parish priest formed a search party that found and followed giant footsteps in the snow. They led to a hulk lying still under a thick blanket of snow. When the priest leaned over to see what sort of beast this was, his crucifix glinted in the lantern light. A weak voice whispered, “Père” (Father).

The “monster” was actually a man encased in ice.

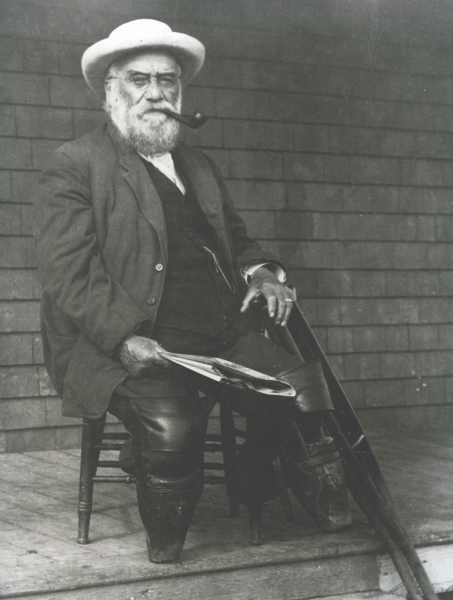

My mother recognized this man because she had seen his photo in family albums. He was her great-uncle Augustin Le Bourdais.

The magazine story soon became family lore, at least among the members of my close family. But was it completely true? We lived then on the other side of the continent, in Portland, Oregon, and no longer had a connection to our French-speaking relatives in Quebec. Decades later I mastered French — the only one in my family to do so — and I felt compelled to learn more about my great-great-uncle.

I Googled his name and came across a book entitled Auguste Le Bourdais, naufragé en 1871 aux Îles-de-la-Madeleine (1979) by Azade Harvey. Harvey, who passed away in 1987, wrote a book based on equal parts fact and legend, including fictionalized conversations and anecdotes.

I also contacted the Magdalen Islands Musée de la Mer, which put me in touch with Guy Le Bourdais, Auguste’s grandson in Quebec City. Guy Le Bourdais has his grandfather’s journal, as well as a letter Augustin wrote to his parents about the shipwreck. After communicating with Guy, reading his book on Le Bourdais’ genealogy containing the definitive version of events, and visiting the Magdalens in 2013, I pieced together this story:

Eldest son of twelve children, Augustin Le Bourdais, dubbed Auguste, was born in l’Islet, Quebec, in 1844. He developed into an exceptionally strong young man, well over six feet tall and two hundred pounds. Inspired by sailor cousins, Le Bourdais went to sea at the age of fourteen.

By the time he was twenty-seven, he had sailed as far as India and had worked his way up to first mate — second only to the captain. In November of 1871 he signed on to the brig Wasp. His youngest brother, François-Assise, was also part of the crew.

As many as 450 ships have been wrecked off the islands, often leaving only a single survivor.

The ship sailed east from Quebec City just before midnight on November 24, loaded with wheat and oats destined for Belgium. Violent winds forced them to anchor in Gaspé until November 27.

The next day, the ship set sail despite vicious ninety-kilometre-per-hour winds laden with snow. The Wasp was driven toward shoals off the Magdalen Islands between Pointe-aux-Loups and L’Étang-du-Nord. Le Bourdais described the ensuing ordeal in a letter to his parents: “We ran aground on a Tuesday night, November 28 ... the weather was so terrible that I don’t even know what happened.”

Repeated attempts to launch lifeboats failed; huge waves several metres high battered the ship all night long. Le Bourdais used a long woven belt — a ceinture fléchée — to lash himself to the base of the bowsprit, where he was somewhat sheltered from the pounding waves. In the terrifying dark the sailors called out to one another after each huge wave. One by one the voices were silenced during the night, including that of François-Assise.

As the soaked cargo swelled, the sides of the ship’s hold began to give way. Late the next day, Le Bourdais realized the ship was breaking up, so he attached himself to a section of deck. His foot caught between two boards of this makeshift raft, and waves washed him ashore, unconscious.

His letter goes on: “The snow was so thick I couldn’t see where I was or which way to go. Out in sleet, ice and driftwood with frozen clothes, consumed by thirst and hunger, my strength was nearly gone. The violent storm continued from Wednesday until Sunday. I was completely alone.”

Wet and exhausted, Le Bourdais saw a pile of dune grass, which the people of the islands would gather every fall to use as spring fodder. He dug out a partial shelter at the base of the stack and fell asleep. By the time he woke up, his feet were frozen. There he stayed from Thursday to Sunday, “getting weaker... unable to move... waiting for death which would not come.”

The weather finally cleared on Sunday. Alone and grief-stricken, he had literally frozen in a storm that howled for five days and wrecked two other ships, adding five deaths to the ten who died on the Wasp.

“I saw a man very far off, too far away to hear me call,” Le Bour-dais said in his letter. “I began to move toward him and saw smoke from a hut some distance away. That gave me courage and I succeeded in dragging myself over that way.” A number of men eventually saw him crawling toward them and came out to rescue him.

He was no longer alone, but the next part of his ordeal had just begun. Le Bourdais’s feet were indeed frozen right through and had to be amputated. Solomon Riopel, an Anglican priest who also practised medicine, performed the surgery with a handsaw and some shoemaker’s tools. The only anaesthesia available was a great quantity of rum, and it took eight men to hold him down during the operation. To make matters worse, Le Bourdais later contracted gangrene.

When the ice broke up the following spring, he was transported in excruciating pain to Quebec City, where a second double amputation was performed just below the knees. After more than a year of convalescence in hospital, he could walk with the help of crutches and homemade wooden prostheses strapped on above and below the knee.

Le Bourdais then went on to learn Morse code and telegraphy. But it was not easy for him to find work. He had to petition his Member of Parliament for employment. Finally, in 1879, he was hired to operate the Magdalens’ first telegraph station.

The coming of the telegraph was a momentous event for people on the islands because ice choked off navigation for six months of every year, leaving them completely isolated from the rest of Quebec and the Maritimes. Being connected at last to the outside world during the long winters greatly changed islanders’ lives.

As a telegraph operator, Le Bourdais had a position of some prominence. He eventually became district supervisor on the Magdalen archipelago, overseeing the building and operation of the islands’ ten telegraph stations and offices.

Having become settled in his work, he also established a home life. He married island schoolteacher Émilienne Renaud and fathered six children.

Today, nearly every Madelinot knows the name of Augustin Le Bourdais. Not a “monster,” but extraordinarily robust, he was a key player in island communications. He also held a special place in islanders’ hearts because, not only was he shipwrecked there — as many as 450 ships have been wrecked off the islands, often leaving only a single survivor — he returned to the Magdalens to live.

Despite having been robbed of his seafaring future and his lower legs, Le Bourdais had a presence in the Magdalen Islands that was larger than life.

Most of all, in an archipelago that knows shipwreck and fatality all too well, my great-great-uncle’s extraordinary tale of survival also made him larger than death.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement