The Foundering Fathers

Sir John A. Macdonald. George Brown. George-Etienne Cartier. Charles Tupper. Hector-Louis Langevin. Alexander Galt. The men called the Fathers of Confederation have had bad press.

For years historians and politicians condescended to them as hayseed colonials who stormed no barricades, overthrew no tyrants, and hardly founded a nation at all. Surely they had no deep thoughts about democracy and good government, except perhaps to oppose them.

They were not democrats and did not want to put Confederation to the people. They were all men. They created the Senate! Even if they were good enough for the 1860s — that simple time! — they surely did not know anything about telecommunications or the environment. Whatever they did achieve was the work of that schemer John A., who drank.

In recent years, some historians have begun to challenge this dismissive account. Janet Ajzenstat, Paul Romney, John Ralston Saul, and I, among others, have all taken new looks at the Canadian founding and come away more impressed.

It’s a good time to take a look at what have been presented as the failings, the weaknesses, and even the really dumb ideas of the parliamentarians who drafted our Constitution.

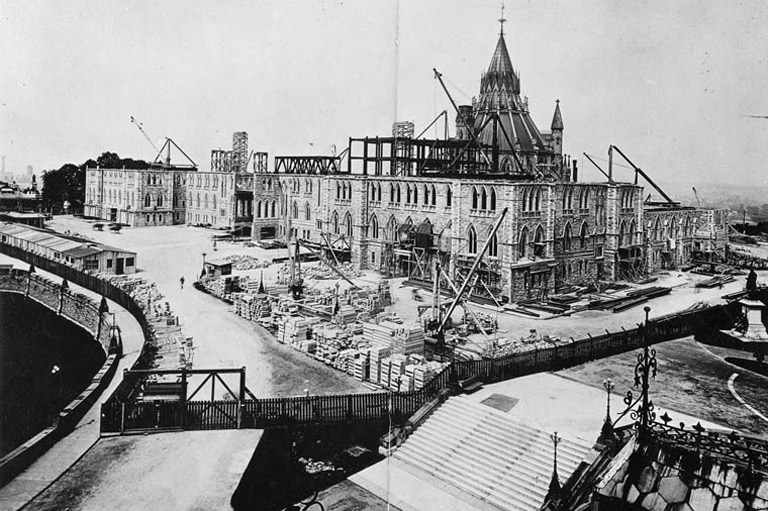

The fall of 2014 marked the 150th anniversary of the conferences where those Fathers drafted the Constitution under which we still live. In September 1864 at Charlottetown, delegates of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Canada (today’s Ontario and Quebec) reached agreement on the broad principles of Confederation.

In October 1864 in Quebec City, with Newfoundland represented, too, they hammered out the details of the union in seventy-two resolutions that are still the basis of our Canadian Constitution.

In 1866–67 in London, England, those resolutions were adapted into proper constitutional language, and the British Parliament made them into law as the British North America Act. But the fundamentals had been worked out in Canada, by Canadians, in the fall of 1864. It was “a scheme not suggested by others or imposed upon us, but the work of ourselves,” said D’Arcy McGee.

Could it be that they were smarter than we think? And are there some topics where Canadians have been wise to move beyond what these men decided — or maybe still need to.

Complaint #1: They were not democrats.

WHO SAYS SO?

You can find it in half the textbooks. Indeed, they said so themselves. Cartier declared that Canada would have nothing to do with “purely democratic institutions.” Besides, hardly anyone could vote, and no women at all. How was that democratic?

SMARTER THAN YOU THINK?

“We are a democratic people,” George Brown’s newspaper The Globe declared proudly in the midst of the Quebec Conference of 1864. The makers of Confederation were democrats — parliamentary democrats. They were not much for what we call direct democracy.

By “purely democratic institutions” they meant what we might call mob rule, and they opposed it. They believed in “government by discussion,” in a legislature where the executive would be reined in by the elected representatives of the people. They believed that government by a parliament, with a permanent rivalry between the ins and the outs, was the best possible safeguard of the people’s rights and interests.

Women did not vote in their world. In Canada, as everywhere else in the world, patriarchy ruled. But in the 1860s, Canada had one of the broadest electoral franchises in the world. The politicians were accountable, not to every citizen but to every household. Elections were lively and hotly contested, and there were few safe seats. Those politicians were hardly free to disregard the electorate and do whatever they pleased.

So the Confederation deal struck at the conferences of 1864 was negotiated by government and opposition members together. They spent weeks at it, face to face. They had fierce disagreements, and no one got everything he wanted. Their agreement then had to be ratified by the provincial legislatures that had sent them. That was no rubber stamp, either. Four of the five legislatures at first refused to ratify the deal.

Both Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland stayed out in 1867. The only provinces that joined were ones where elected legislatures accepted Confederation.

Complaint #2: They created the Senate, ’nuff said!

WHO SAYS SO?

The Senate was “the worst system that could ever be devised” anti-confederate Antoine Dorion said in 1865, and for 150 years just about everybody has agreed. unequal, unelected, ineffective, illegitimate! What were they thinking? canadians have been dreaming of senate reform for as long as there has been a senate.

SMARTER THAN YOU THINK?

In 1867, every parliament in the world had two chambers, one representing the people, the other functioning more or less to control the unbridled will of those representatives of the people. The Confederation makers accepted the two-house model: Canada got the Senate and the House of Commons. But the bedrock of their Constitution was a government based on rep by pop — representation in the House of Commons that was directly linked to population size.

In 1864 the Confederation makers had faith in the House of Commons, the one based on rep by pop. Staunch parliamentary democrats, they did not want an upper house that could override the choices made by the people’s representatives. To have an upper house and keep it from power at the same time, the Confederation makers settled on making the Senate appointive.

They knew appointed Senators would never have the authority to defy the Commons. Ever since, people have said many things about the Senate, but no one ever said it was too powerful. The Confederation makers would have been satisfied with that.

In ensuring the weakness of the upper house, they took a fundamentally democratic step. In the United States, the very non-rep by pop Senate has huge powers; in Britain in 1867, the aristocratic House of Lords could veto anything the Commons did. Not so in Canada.

The Confederation makers made airy speeches about the Senate providing sober second thought and somehow representing regional interests in Confederation. But to keep the elected, representative Commons powerful, what they really needed was a weak Senate. You know they succeeded in that!

Complaint #3: They did not understand the West, Quebec, environmental policy, federal-provincial relations.

WHO SAYS SO?

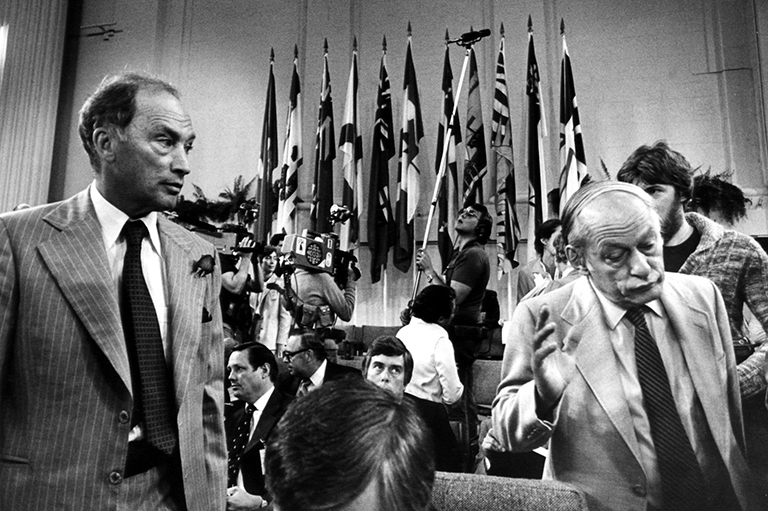

During the creation of the Meech Lake Accord in 1987, one of the premiers said the Fathers of confederation were all right for their time but they did not know much about telecommunications or the environment. Canada’s constitutional wrangles in the last half century were based on the idea that any constitution made in the 1860s was out-of-date, and we could surely do better today.

SMARTER THAN YOU THINK?

It is true that none of the Confederation makers had ever been to the West, and there were no western representatives at the 1864 conferences. Quebec has changed profoundly in 150 years, and no one then foresaw gay marriage, aviation, securities regulation, or employment insurance. Matters that were never dreamed of at the Quebec Conference come up constantly in Canadian constitutional policy.

The Confederation makers may not have known much about telecommunications, but they did know something about drafting a constitution. In any federation, deciding what should be local and what should be national is an endlessly changing challenge.

They seem to have had a rule of thumb: Matters that reinforced local communities and local cultures — education, social services, local government, the use of Crown lands and resources, even the courts — should be run locally. One of their seventy-two resolutions declared that the provinces would run “generally all matters of a local or private nature,” and, generally, they still do.

To Ottawa they assigned the things that helped build a united national space for general prosperity: the military, foreign affairs, customs, trade and commerce, banks, money, even postage and censuses and copyrights. Each level of government had its own set of responsibilities.

Each could raise taxes to support itself. There were courts as well as legislatures to sort out disputes. Most importantly, each province and Ottawa had its own government and legislature, and in the end it was accepted that neither should prevent the other from running its own affairs.

Over 150 years, it has sometimes seemed that Ottawa has had too much power; sometimes that the provinces did. Canadians often struggle to sort out whether new matters are rightly provincial or federal, and debatable choices have been made.

Who pays is a constant challenge, too, and the Confederation makers did some horse-trading themselves on these matters. But they could see that it was better to lay down some big general rules and to let the future apply those rules to new situations. They said nothing about telecommunications, which did not exist, but they also said nothing about, say, buggy-whip manufacturing, which did.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Complaint #4: Really, they were just colonials. Canadian independence came much later.

WHO SAYS SO?

In the next few years, we will often hear that Canada really became a nation just a century ago, at Vimy Ridge; or by the Statute of Westminster in 1931; or by patriation of the Constitution in 1982; or some other date. The British North America Act was a British law, not a canadian one. Even our Governor General was British until 1952.

SMARTER THAN YOU THINK?

In 1867, Canada was a small country in a big world. Canada needed and wanted British support, and most Canadians wanted to know that the new nation was part of a larger empire. But the British North American provinces had been governing themselves since 1848, and Confederation united them but did not change those powers.

The principle from 1848 was carried on in 1867: In its own sphere of affairs, a government accountable to a parliament elected by the people was sovereign, and no outside authority had a legitimate right to interfere.

That principle would protect the provinces from Ottawa’s interference. It protected Ottawa from London as well. The Confederation makers wanted to lean on Britain for many things, but they had great confidence that, in anything they wanted to run themselves, they had the authority they needed.

Sent to Britain with the Quebec Conference’s seventy-two resolutions in 1864, George Brown reported back happily about the British government: “If we insist, they will put through the scheme just as we ask it.” And they did. The Confederation makers had the same confidence that Canadians would run as much of their own affairs as they ever wished. “We hail the birth of a new nationality,” Brown proudly said in his newspaper on July 1, 1867.

Complaint #5: If they were so smart, why did we have to wait over a hundred years for a Charter of Rights and Freedoms?

WHO SAYS SO?

Since it was introduced in 1982, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms has become one of the most popular parts of the Canadian constitution — so popular, in fact, that today Canadians sometimes talk as if our rights were invented in 1982 and the confederation makers gave us a constitution without any rights.

SMARTER THAN YOU THINK?

Hmm. Tricky question! The Confederation makers of the 1860s talked about rights, and they believed that rights mattered. But they truly were parliamentary democrats. They had vast confidence that parliaments could be relied upon to defend rights against meddling, or arbitrary or even tyrannical governments.

They did not believe that anyone else could, or should, have the right to try So the Confederation makers rejected the idea of the American founders and the French revolutionaries. They did not “entrench” a list of rights with which the legislature could not interfere. They believed they had “the rights of Englishmen;” mostly, that meant a parliament of their own and the English common law tradition.

That was a noble idea. But Parliament did not stop Canadian governments from implementing the War Measures Act; or imposing the head tax on Chinese immigrants; or permitting petty bureaucrats, police officers, and administrative agencies from infringing on the rights and freedoms of ordinary Canadians in a thousand small ways.

Before the Charter came into force in 1982, there was no remedy for situations when Parliament could have intervened but chose not to do so.

There are some who argue that our rights now depend on unelected judges, accountable to no one, and maybe that is not a good thing — because, if we do not like what they decide, too bad. Thirty years of experience with the Charter may be too soon to judge how entrusting our rights to judges will work out.

But mostly, Canadians like knowing that they have rights, knowing that they are written down, and knowing that the politicians mostly cannot mess with them.

Score one for us over the Confederation makers, I think. There is still a lot for governments and parliaments to do.

Complaint #6: Can anybody say the Confederation makers did right by the First Nations of Canada?

WHO SAYS SO?

Read The Inconvenient Indian the recent prize-winning book by the terrific Indigenous writer Thomas King. The confederation makers built a transcontinental nation, but the First Nations ended up poor, dispossessed of their land, dependent on government agents for almost everything, poorly provided with good schools, clean water, decent housing, reasonable job projects, or control of their own communities.

Almost everywhere, First Nations are still demanding to have their Indigenous and treaty rights respected.

SMARTER THAN YOU THINK?

You might say the Confederation generation of politicians started well. They accepted the principle that the Crown of Canada had to build and maintain treaty relationships with the First Nations of Canada.

As Canada expanded rapidly west and north, the government negotiated treaties that came to cover most of Canada. And, in the negotiations, respect was often paid to the rights and interests of the First Nations: “as long as the sun shines and the grass grows”; “the land will always be yours”; “you may hunt and fish forever.”

But, within a decade of Confederation, the same politicians introduced the Indian Act that gave Canada vast powers to confine Indigenous people to reserves, to dictate how they lived their lives, and to use treaty lands as suited the government, not the people living there.

All kinds of theories of “what was best” for First Nations could be tried out, and the idea of a treaty relationship between partners seemed to be lost completely. They did not do a very good job on that score, but it is not as if later generations have done better.

Save as much as 52% off the cover price! 6 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital.

Complaint #7: If their parliamentary system was so great, why does our parliament look such a mess most days?

WHO SAYS SO?

These days, who doesn’t?

SMARTER THAN YOU THINK?

The thirty-three men of the Charlottetown and Quebec conferences were politicians, delegated by their legislatures and obliged to report back to them. They were not all political geniuses; maybe we should not even call them father figures.

The Supreme Court of Canada has repeatedly said that the Constitution they devised is a “living tree,” not something fixed and changeless but a set of principles that must grow and adapt to changing circumstances. On the other hand, Canada has done pretty well with the political system in which they worked and with the constitutional principles they worked out 150 years ago.

If our Parliament is not working well today, surely that is our problem to solve, not theirs. On the 150th anniversary, give the Confederation makers their due.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk necktie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. Made exclusively for Canada's History.