Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

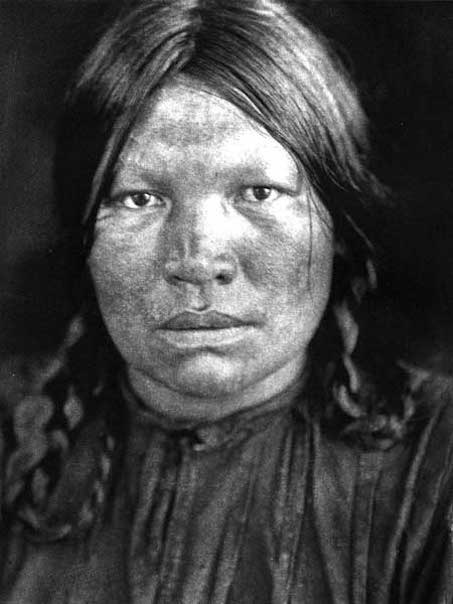

Thanadelthur

One of the few women to have been accorded a place in the history of the Canadian North is Thanadelthur, a remarkable Chipewyan Indian better known as the Slave Woman. Her fame rests on the successful outcome of an arduous journey undertaken for the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1715–16.

Several authors have told the story of how Company servant William Stuart with the aid of the Slave Woman negotiated a peace between the Cree and Chipewyan tribes which paved the way for the establishment of a fort at the mouth of the Churchill River. Little attention, however, has been given to Thanadelthur as a personality in her own right or to her position at York Factory after the conclusion of the peace mission as Governor James Knight’s “advisor.”

In the journals of York Factory, Thanadelthur is always referred to as the Slave Woman. She, along with other of her countrywomen, had been captured by the Crees in a raid upon the Chipewyans in the spring of 1713. The Crees, being the first to obtain guns from the traders, had gained the ascendancy in this tribal conflict and so devastating had their attacks been that one branch of the Chipewyans came to be known as Slaves.

According to Chipewyan oral tradition, the Slave Woman’s real name was Thanadelthur which meant “marten shake.” The explorer Samuel Hearne, an astute observer of Chipewyan society in the later 18th century, recorded that girls were usually named after some part or property of the marten.

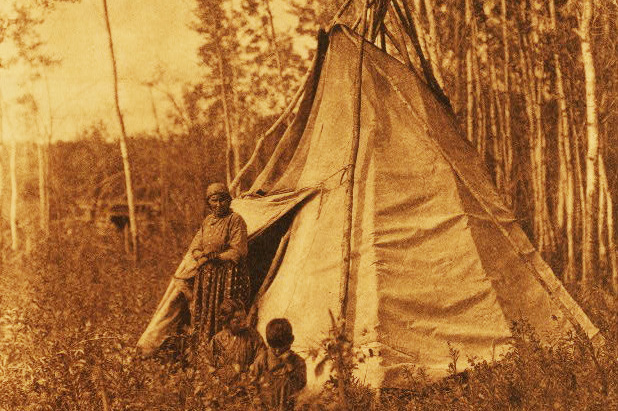

Although inaccurate in specific detail, it is notable that the story of Thanadelthur as handed down by the Chipewyans emphasized her youth and attractiveness. If Chipewyan women, in general, failed to conform to the Englishman’s ideal of beauty, Hearne conceded that many were of “a most delicate make” and “tolerable” when young.

Owing to her difficult way of life, a girl’s beauty was particularly fleeting. Given in marriage when very young, the care of a family added to her constant hard labour rendering even the best-looking woman old and wrinkled before she was thirty. It is probable, therefore, that Thanadelthur was in her teens when captured by the Crees.

Strong, young women constituted a valuable prize in warfare since female labour was of such importance in a nomadic society. Apart from being “a handsome young woman,” Thanadelthur possessed a forceful and intelligent character — a combination which captured the interest of the doughty old governor of York Factory, James Knight.

In the fall of 1714 when James Knight reclaimed the fort from the French under the Treaty of Utrecht, he was anxious not only to re‐establish English trade but to extend it northward. The existence of the Chipewyans or Northern Indians was known, but their fear of the Crees prevented them from venturing to the Bayside. Knight’s only contact with the Northern Indians was through his chance meeting with female captives held by the Crees.

Thanadelthur was not the first “Slave Woman” to seek refuge at York Factory. That fall another Chipewyan woman had escaped and made her way to the fort. The information she had given Knight about her country sealed his determination to establish a trade with the Chipewyans. This first woman sickened and died on 22 November. Knight was lamenting his loss when two days later, Thanadelthur was brought in “Allmost Starv’d.”

She had a harrowing tale to tell. Earlier in the fall when camped on the north side of the Nelson River, Thanadelthur with another of her countrywomen had escaped from their Cree master, hoping to make it back to their people before the winter set in.

They had only the catch from their snares to subsist on and when cold and hunger finally drove them to turn back, the two women clung to the wild hope that they might find the traders whose wondrous goods they had seen in the Cree camps. Only Thanadelthur survived. Several days after her companion had perished, she stumbled across some tracks which led her to the tent of the Company’s goose hunters at Ten Shilling Creek.

Knight was immediately impressed with his new informant who spoke encouragingly of her people and their rich fur resources. Even though her present knowledge of the Cree language was indifferent, she would be of “great Service to me in my Intention” he wrote enthusiastically. To ensure the success of his plans, Knight realized that he must first endeavour to establish peace between the Crees and the Chipewyans.

Sign up for any of our newsletters and be eligible to win one of many book prizes available.

Early in June 1715, the Governor gave a feast for his “Home” Crees and persuaded them to send a peace delegation to their enemies. They were to be accompanied by one of the Company’s servants, William Stuart, and the Slave Woman. Bands of “Upland” Crees coming in to trade were also encouraged to join the peace mission, so that the party which set off on 27 June numbered about one hundred and fifty.

Knight entrusted Thanadelthur, who was to act as interpreter, to the special protection of Stuart. He directed him to “take care that none of the Indians abuse or Missuse the Slave Woman.” He gave the Chipewyan woman a quantity of presents to distribute among her people, instructing her to tell them that the English would build a fort on the Churchill River in the fall of 1716.

Thanadelthur, who readily appreciated the importance of her position, soon became the dominating spirit of the expedition. Stuart was amazed at the way she kept the Crees in awe of her and “never Spared in telling them of their Cowardly way of Killing her Country Men.”

Disaster stalked the enterprise, however. Slowed by sickness and threatened with starvation on the long trek across the Barren Grounds, the party had to break up to survive. Most of the bands turned back, leaving only Stuart, the Slave Woman, and the Cree captain with about a dozen of his followers determined to find the Chipewyans .

Failure seemed certain when Stuart’s party stumbled across the bodies of nine Northern Indians, slain by one of the other Cree bands. Fearing the revenge of the Chipewyans, the remaining Crees now wanted to abandon the search.

At this juncture Thanadelthur seized the initiative. She persuaded the Crees that if they would wait ten days she would be able to find her people and return with them to make peace. She left the Crees to fortify their camp in case of attack and within a few days she came upon a large band of her countrymen.

It required all her powers of persuasion to get them to return with her; she had to make herself hoarse “with the perpetuall talking” before the Chipewyans could be convinced of the pacific intent of their enemies. In true epic fashion on the tenth day, Thanadelthur and two emissaries came in sight of the Cree camp . When Stuart came out to meet them and conduct them to his tent, she signalled to the rest of the delegation, over a hundred strong, that it was safe to approach.

According to oral tradition, Thanadelthur was placed on a raised platform, “so that her people could see her and have confidence. When she beheld her people coming, she sang with joy.”

With the help of the Cree captain, Thanadelthur once again assured her people that their party bore no responsibility for the recent unfortunate raid upon the Chipewyans and that the Crees were most anxious for peace. With those who remained doubtful, this forceful diplomat had no patience:

She made them all Stand in fear of her she Scolded at Some, and pushing of others ... and forcd them to ye peace.

William Stuart was full of admiration:

Indeed She has a Divellish Spirit and I believe that if thare were but 50 of her Country Men of the same Carriage and Resolution they would drive all the Northern [Southern] Indians in America out of there Country.

Stuart’s party arrived back at York Factory on 7 May 1716, accompanied by ten Chipewyans one of whom appears to have been Thanadelthur’s brother. The Englishman emphasized that the mission owed its success to his remarkable Chipewyan ally who had been “the Chief promoter and Acter” of it.

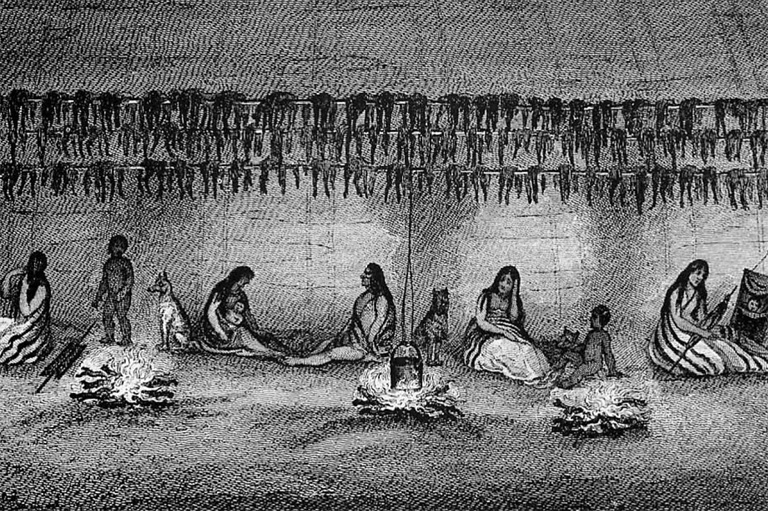

Considering the status of women in Chipewyan society, how would it have been possible for Thanadelthur to attain such a prestigious position? In the eyes of the traders, Chipewyan women led a degraded existence. They served as beasts of burden and their misery, in an endless round of domestic drudgery, was intensified by the harshness of the northern environment. “What is a woman good for ... she is only to work and carry our things” a Chipewyan explained to David Thompson.

Samuel Hearne observed women carrying up to one hundred and fifty pounds in summer and hauling a much greater weight by sled in winter. He was shocked to discover that in times of scarcity the women were the first to suffer. Although he denounced this unchivalrous treatment of women, Hearne admitted that it arose from their nomadic way of life, where the men had to be left free to hunt, and that “custom makes it sit light on those whose lot it is to bear it.”

Furthermore, it appears that the women were not entirely without influence within the tribe. According to Alexander Mackenzie’s account of the Chipewyans, although “the women are as much in the power of the men, as any other articles of their property, they are always consulted, and possess a very considerable influence in the traffic with Europeans, and other important concerns.”

Thus, Thanadelthur could expect to command attention when she brought news that the English traders intended to establish a trading post for the Chipewyans. Her favoured position was indeed derived directly from her connection with the traders. William Stuart was often afraid that her constant berating of the Crees of their party might have provoked them to kill her “had I not given them such a Strict Charge not to Abuse her.”

To her own people, Thanadelthur was their link with the English who promised to trade marvellous goods, particularly guns which would help them to improve their hunts and to withstand their enemies. As a result of the peace mission, Governor Knight declared, the Slave Woman had earned considerable respect and “Carry’d a Great Sway Among the Indians.”

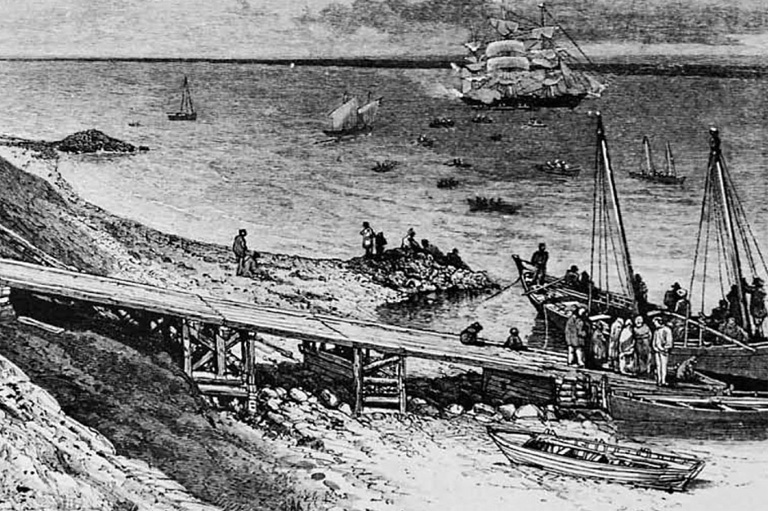

It had originally been Knight’s intention to send the Chipewyans, including Thanadelthur, back to their own country in the autumn of 1716. The season of 1715–1716 had been a disastrous one at York, however, owing to the non‐arrival of the annual ship and he was forced to postpone his plans for establishing the post at Churchill.

Having recently endured the hardship of the long trek to the factory, the Chipewyans were not ready to return; they were afraid of being killed when passing through the country of the “Upland” Crees who had not been party to the peace ceremony. Knight, therefore, allowed them to winter at York — Thanadelthur and three others within the fort, the rest with the “Home” Cree.

Since the return of the peace mission. Thanadelthur had “know’d well Enough’ how to make lhe most of her exalted status. Devoted to the traders’ interests, she instructed her companions as to what furs were valuable and how to prepare them.

When one old Chipewyan had the audacity to suggest that less than prime pelts should be accepted, she was most incensed. She “ketcht him by the nose Push’d him backwards & call’d him fool and told him if they brought any but Such as they were directed they would not bee traded.”

Yet Thanadelthur herself was not without duplicity. In June, Knight made her a present of a little kettle to take with her on her return journey. His feelings were injured when soon after he discovered that she had given it away; he taxed her for this lack of regard and she denied it. Knight then confronted her with the offending kettle, whereupon Thanadelthur flew into a rage, claimed the kettle had been stolen, and threatened the old governor that if he ever set foot on Churchill River she would direct her people to kill him.

“She did rise in such a passion as I never did see the Like before” declared Knight. so “I cuff’d her Ears for her.” When her fit of temper achieved nothing, Thanadelthur resorted to more feminine wiles to regain the sympathy of Knight.

The next morning she came penitently to him and through her tears, admitted that she had been “a fool & Madd.” She hastened to assure Knight that he was like a father to them all and vowed that he would never come to any harm because she and all her people would always love him.

Thereafter, Thanadelthur appears to have behaved admirably. She now possessed considerable fluency in both Cree and English and never missed an opportuni1y to sing the praises of the Hudson’s Bay Company to both the Chipewyans and the Crees. Knight was more interested, however, in the stories she told of rich mineral deposits somewhere to the northwest.

According to Thanadelthur, her countrymen had promised to bring “a great deal of copper” when they came to visit the new post at Churchill. Even more exciting was the news that the Chipewyan knew of others who possessed a “yellow mettle” which Knight took to be gold. The governor was now determined that the post at Churchill must be established as early as possible in the summer of 1717.

Being highly impressed with the “Extraordinary Vivacity” of her quick mind, Knight sought Thanadelthur’s advice for all his plans, she “Readily takeing anything right as was proposed to her & Presently Give her Opinion whether it would doo or not.”

Thanadelthur was enthusiastic about Knight’s proposal that she should again travel to the Chipewyans to explain that the English had been delayed but would definitely build their fort at Churchill the coming summer. Although sometime during this period she appears to have taken a husband, probably one of the Chipewyans who had accompanied her back to York, Thanadelthur refused to let marital duties interfere with this important commission.

She informed Knight that she would leave her husband if he would not accompany her. Imbued with a sense of mission, Thanadelthur had decided that she could “never rest” until she had spread the news of the coming of the English traders amongst all the Chipewyans, a task which would take about two and a half years. She and her companions were to leave in the early spring of 1717, accompanied by the young apprentice, Richard Norton.

The extremely severe winter at York unfortunately proved disastrous for the Chipewyans. The conditions at the factory, so different from “their Naturall way of Living,” and the want of “fresh Victuals” caused several, including Thanadelthur, to fall ill. On 11 January, Knight recorded in his journal: “ye Northern Slave Woman has been dangerously Ill and I expected her Death every Day, but I hope she is now a Recovering.”

The governor worked unceasingly trying to nurse the ailing Chipewyans back to health. He would suffer a serious setback in losing his only interpreters and was also afraid of the “Jealousy & Suspicion” that might result among the other First Nations should they die.

Although on her deathbed, Thanadelthur struggled bravely. She called the “English Boy” who was to have gone with her to learn the language, to her bedside and told him not to be afraid to go with her people. She assured him that her brother, whom she had asked Knight to designate a captain, “would love him and not lett him want for anything.” Four days later, on 5 February 1717, Thanadelthur died. “I am almost ready to break my heart” wrote Knight in despair.

He tried to conceal her death from her companions, three more of whom were to die within a month, but they “Quickly came to Understand it.” After she had been buried, Knight gave all Thanadelthur’s possessions to her mother and her brother as she had requested shortly before she died.

He also gave some small gifts to her friends “to Wipe away their Sorrow.” The old governor’s grief lay deeper than in the fact that Thanadelthur’s death “will be very Prejudiciall to the Companys Interest.” He had come to regard this woman as one of the most extraordinary people he had ever met:

She was one of a Very high Spirit and of the Firmest Resolution that ever I see any Body in my Days and of great Courage & forecast ...

With bitter irony, Knight ended his journal entry for February 5: “the finest Weather wee have had any Day this Season but the most Melancholys’t by the Loss of her.”

So heavily did Knight rely on the interpreting services of Chipewyan women that he managed with great difficulty to secure another Slave Woman though she cost him “above 60 skins value in goods.” This woman set off with Richard Norton in July of 1717 to contact the Chipewyans while an advance party of Company servants sailed to the Churchill River to begin construction on the new post.

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!