Seduction and the Law

A Winnipeg woman—mid-thirties, attractive, a professional—fell victim recently to a Casanova, twenty-first-century style. Their six-week “relationship” consisted of him sexually exploiting her. She was his sexual conquest. Once he attained victory, he was gone.

He used no physical force. He simply laid siege to her psychologically until she slept with him. Then he decamped, never to be heard from again. “I should have known he was no good,” she said. “One time he described himself, at least half seriously, as ‘the Hercules of love.’”

He left her hurting. The stress and trauma that flowed from her being the victim of a sexual escapade manifested itself in physical symptoms—loss of appetite, loss of sleep, and inability to perform, or some days even go to, her job.

“It goes beyond me,” she told the lawyer she consulted. “What also grinds is his attitude to women. I hate the thought that to him I was just the latest in a long line of tasty cupcakes. I’d like to get him for that.”

But she can’t—at least not legally.

Until the 1980s (or 1990s in some provinces), she, or her father, or even her employer, could have sued the likes of him. Appropriately this type of lawsuit was called a seduction action. It enabled a woman to sue for a sum of money to compensate her for general pain and suffering (which included her humiliation or distress), loss of income due to inability to do her job, and, if the seduction resulted in childbirth, expenses related to pregnancy and birth.

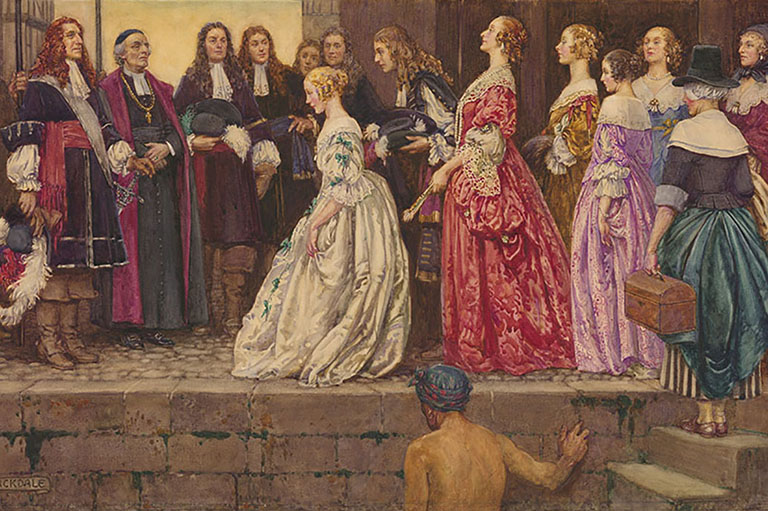

Seduction suits originated in English common law. In nineteenth-century England, a young woman’s father or master could sue for monetary damages for the debauching of an unmarried daughter or female servant. The woman herself had no legal status and no say in the matter. She could neither sue nor prohibit her father or employer from suing.

Canada inherited seduction claims via its piecemeal adoption of the English legal system. Receipt of English law in the provinces and territories varied. Sometimes English law was adopted when a colonial legislature was established, sometimes when a territory was admitted to the Dominion (as was the case with Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory), and sometimes when a province was created. Nonetheless, by the late nineteenth century, Canadian courts uniformly applied English law, including seduction suits.

Quebec was the exception. After Quebec’s fall to the British, it, too, was governed by English law for an eleven-year span, by virtue of the Royal Proclamation of 1763. However, French civil law was reinstated with the Quebec Act of 1774.

A father’s or employer’s claim had its basis in nineteenth-century notions of proprietary rights. An unmarried daughter or maidservant was akin to property, which could be impaired or diminished by seduction. Whether the daughter or servant voluntarily, or even enthusiastically, participated in an “act of carnal intercourse” was irrelevant. Particularly where the plaintiff—the person who sues—was the father, regardless of the circumstances, a seduced daughter constituted an affront to paternal dignity and an injury to paternal rights.

The suing father had to prove he suffered harm from the sexual liaison, usually by way of loss of services. This wasn’t hard to do. Courts bent over backwards to find loss—so much so that many commentators described the requirement of proving damages as a legal fiction.

Pregnancy wasn’t necessary. Any modest psychological distress to the girl or woman, such as worry or regret, was good enough. Nor did the loss of daughterly services have to be substantial. As one judge put it, “Making tea has been held to be an act of service.”

Seduction suits proceeded from a legal presumption—rebuttable by contrary evidence—that a woman wouldn’t let herself be seduced, or ever be the seducer.

Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Canadian judges favoured a view of women as naive innocents liable to flounder on the shores of male lust. Any attempt to depict a young woman as a latter-day Delilah ran smack dab into an ethos that deemed women inherently modest and naturally programmed to resist the male’s crude sexual overtures. A passionless female sexuality was the avowed, though not altogether true, ideology of the Victorian and Edwardian eras, and for several decades beyond—an ideology propounded in ministerial and medical advice and reflected in Canadian courts of law. “Lie still and think of the Empire,” Queen Victoria’s supposed (and likely apocryphal) wedding-night advice to her daughter, nicely caught the prevailing attitude.

Defendants who tried to portray a woman as wily, conniving, or “loose” had to adduce overwhelming evidence she was a femme fatale. Woe betode he who alleged a lady was mad, bad, and dangerous to know, and couldn’t prove it. Judges inclined to inflated awards of court costs against men who couldn’t substantiate their allegations.

Judge-made rules of evidence, often inconsistently applied, further hamstrung male defendants. While a man could reduce the damages he had to pay by proving the woman to be of generally bad reputation, technically he couldn’t present evidence of specific incidents of promiscuity as a defence to the claim itself. The absurd result was that a man who “connected with”—the oft-used delicate judicial metaphor for sexual intercourse—the local Fifi La Tour could discount his damages, but couldn’t escape liability.

Canada initially adopted English law governing seduction holus-bolus. But gradually some jurisdictions passed legislation that altered or codified the common law. While British Columbia and the four Atlantic provinces continued to be governed by common law throughout the twentieth century, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and the Northwest Territories enacted statutes—not surprisingly, entitled The Seduction Act of Ontario, of Manitoba, etc.—in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century.

Saskatchewan and Alberta proved Canada’s progressive jurisdictions: those provinces allowed women to sue in their own right. But while legislative riffs on the common law often heralded female legal and sexual autonomy, they also enshrined defences to seduction claims.

A nineteen-year-old Edmonton hotel waitress’s 1915 suit against a hotel patron for inducing her “to part with her virtue for the first time” created the legal precedent. Because legislation extended the right to sue to an unmarried woman, it was open to an alleged seducer to raise the defences that, in the words of Mr. Justice Scott of the Supreme Court of Alberta, “if she be the tempter or even if she deliberately consents from lasciviousness or even from the strength of mere natural passion” she couldn’t win her suit.

The waitress, a Miss Gibson, claimed “she yielded to the defendant by reason of his promise of marriage.” Considering the day and age, her conduct wasn’t above suspicion.

Miss Gibson was found by the court to have regularly gone “to moving picture shows and other entertainments with young men, some of whom appear to have been of doubtful reputation.” She admitted customarily receiving the defendant alone in her hotel room at night. She also admitted that “in accordance with her usual custom after her work was done, she discarded her skirt and put on a kimona [sic],” which she wore in his presence.

Although the court found “her acts would in some social circles be considered improper,” it refused to infer “she received him with expectation that he would have sexual intercourse with her,” and upheld the trial judge’s damages award.

Nonetheless, the case was seminal for recognizing as a defence that a woman could be complied with, or even the predator in, her seduction. It was also a stunningly candid and progressive assessment of female sexuality. The court, for the first time in Canada, openly acknowledged that women might display sexual appetite or indulge in sexual stratagems.

Over time, seduction suits became infamous for their abuse of the judicial system. By the mid-twentieth century they were a fertile field for blackmail and extortion. Manufactured seduction claims in which the threat of publicity was used to extract an out-of-court settlement were common. Vindictiveness also reared its head in too many cases before the courts. Law-reform-commission reports questioned the motives behind many seduction suits. Some women, went the argument, used the courts not so much to claim damages as to inflict a public and emotionally messy revenge on the man.

Underlining these arguments was the sea change in sexual mores. The sexual revolution of the 1960s, followed by several decades in which unmarried cohabitation became commonplace, made seduction laws look anachronistic. A legal action that smacked of ruined maids and fallen women didn’t have many backers in academic or legislative circles. Most thought seduction a fitting subject for bodice-ripper-genre fiction, not litigation.

By the end of the 1980s every province except Saskatchewan had enacted legislation barring seduction lawsuits. And even in that province the right to sue, restricted to an unmarried woman, had been narrowly interpreted to mean a woman who’d never been married. (A divorcee, therefore, at least in Saskatchewan, could never be seduced. The statute said so.) In 1990 Saskatchewan repealed its seduction act and joined the rest of the country in prohibiting seduction suits.

Not everyone welcomed wholesale abolition of seduction actions. American law professor and author William L. Prosser, writing of a historically parallel movement to ban seduction actions in the United States, believed taking away a woman’s right to sue denies “relief in many cases of serious and genuine wrong.”

The legislative rush to outlaw seduction claims wasn’t well thought out, according to Prosser. “It may be,” he wrote of the many statutes barring seduction litigation, “that they do away with spurious lawsuits at too great a price.”

The seduced and abandoned Winnipeg woman would likely agree.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!