Roots: Name Games

Most Canadians are familiar with the seductive TV commercials for Ancestry, the genealogy research company with “the world’s largest collection of online family history records.” Just enter a few family names, and you will soon be discovering the migrants and miners, the war brides and war heroes from whom you’re descended.

Maybe so, but experienced family historians have learned the hard way that research is rarely simple. Take the case of John, er, John, um . . . Well, let’s just call him John Whatsit for the moment.

I first became aware of John when my friend Ralph’s elderly father — knowing I was a family historian — expressed curiosity about the origins of his maternal grandparents, John and Mary Mount, who had settled in Winnipeg a century ago.

After a little work we documented the marriage of John and Mary in England and the subsequent births of their six children, between 1883 and 1901, in England and Canada. Eventually the Mounts did settle in Winnipeg, just as Ralph’s father had remembered. In the normal course, these findings would have closed my research into the Mount family.

Yet one unusual discovery had come to light in the English 1881 census: John’s father, Charles Mount, was shown as a widowed, German-born bootmaker. I wondered: How strong were John’s Germanic roots?

Going backward in time, I tried to find John Mount in the 1871 census of England on Ancestry. No luck. Similarly I struck out with father Charles Mount and with John’s siblings. There was always the possibility that the family hadn’t been counted, but a more likely explanation was a modern mistranscription of the surname from the enumerator’s hand-written records.

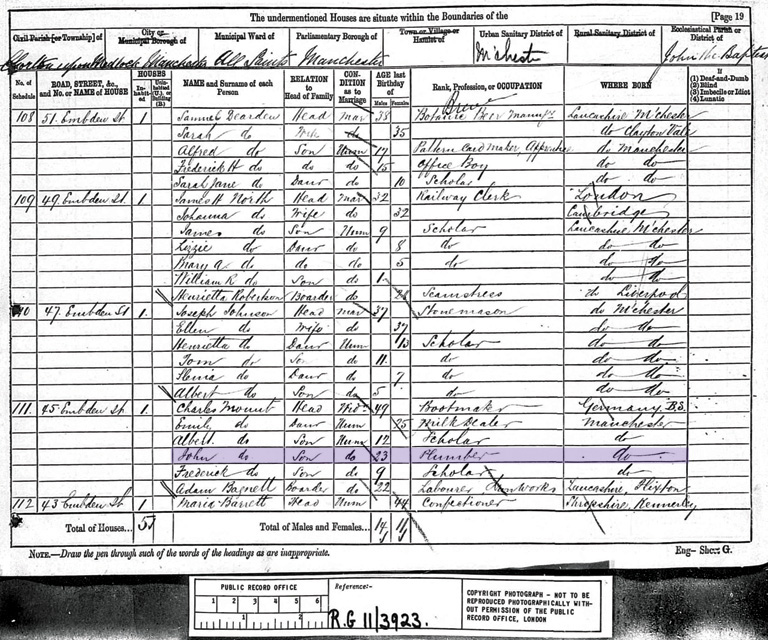

So, I searched the 1871 census for a Charles of unknown surname born in Germany. Lo and behold, Ancestry immediately proposed a family that qualified on all counts: head Charles, a shoemaker born in Prussia; children of the right names and ages, including John in his teens; and a wife for Charles, Rose Ann.

The surprise: The family’s surname was unmistakeably Berg in both the original record and the transcription. So how could the Mounts be the same people as the Bergs? Once you know the answer it’s self-evident — “Berg,” in German, translates into English as “mountain, mount, hill.”

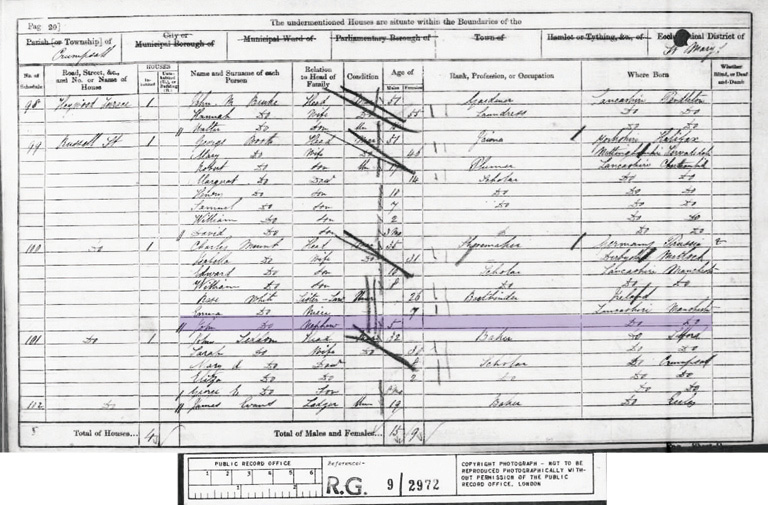

At this point, it might seem as though it would be a snap to go back further in time to locate the young John Berg. But in the 1861 census, he cannot be found. Nor can John Mount. Nor can Charles Berg. Running out of options, I tried Charles Mount — and our German-born shoemaker was back.

But shockingly, he was married to an Isabella! Yet Rose Ann and John had not disappeared. They were listed as members of Charles Mount’s household. Bearing the surname White, they were identified as Charles’ sister-in-law and nephew respectively.

Without even more research, we can only speculate about Isabella’s fate and the subsequent realignment of families. But this is not a column about Charles, Isabella, and Rose, nor is it a reconstruction of the events that roiled their families in the mid-nineteenth century. It’s the tale of research into the seemingly prosaic life of John Whatsit:

- As a young lad in 1861, he was enumerated as John White, nephew of Charles Berg.

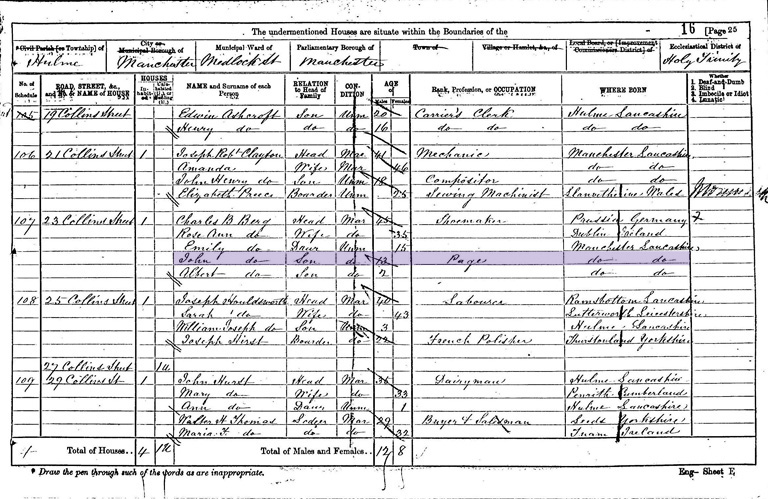

- In his teens in 1871, he appeared on his second census as John Berg, son of Charles Berg.

- And in his twenties in 1881, he morphed into John Mount, son of widower Charles Mount, and so he would be known for the remainder of his days.

Three different surnames, in the first three censuses of his life.

The lessons here? In genealogy, you never know what you’ll find if you keep digging, even in cases that seem straightforward.

And don’t believe anyone who tells you it will be a snap. Yes, the records were eventually found on Ancestry, a resource I would not want to be without.

But no, they didn’t magically appear after simply entering a few names as in the commercials. You might as well have typed in “John Whatsit.”

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!